Digital media travels hand to hand, phone to phone across vast cartographies invisible to Big Data

I stood at the corner of Market Street and 4th Avenue, at the edge of San Francisco's technology-startup neighborhood. An older Chinese woman—let’s call her Fei—approached my friend and me, asking for directions in her extremely limited English. In her hands was a piece of paper with directions from Google Maps, to a location somewhere much further south in the city.

“One second,” I said. “We’ll check the address.” My friend pulled out his phone and punched in the English language address of her destination into a maps app and received a few public-transit options for how to get there.

I asked Fei if she had a phone so I could send her the information, but she said, “I just have a pen.” I ended up writing down the directions on the back of her printout and wished her luck, pointing her in the direction of the bus she needed and double-checking my orientation with my phone’s compass app.

In traditional tech parlance, a phoneless woman like Fei would be considered one of the 4.3 billion who are said to be unconnected to the Internet. The International Telecommunications Union, a branch of the United Nations, measures connectivity via fixed landline, mobile, or broadband subscriptions. Cisco’s Visual Networking Index measures global mobile data traffic to gauge growth in usage. McKinsey and Co.’s research defines the offline population as those who haven’t gone online in the past 12 months.

Following the implicit logic of such statistics, it can be easy to assume that being unconnected means having no exposure to the Internet at all. Phrases like “connecting the unconnected,” “the next billion,” and “the digital divide” all suggest this binary: One either has access to the Internet or doesn't; one lives on the wired side of the tracks or one doesn’t. But as tech ethnographer Jan Chipchase wrote recently, “Connectivity is not binary. The network is never neutral.” Between those who’ve never touched a computer and those who get a feed of data directly into their Google Glass sits a vast array of modes and methods of connectivity.

The most commonly-discussed of these is shared access. Just as a family in the rich world might share a television, families in the developing world often share devices and telecom accounts. In rural Luzon, the largest island of the Philippines, I’ve seen groups of people access the internet via Facebook. One person—the one who is formally connected and counted--has the account, but many others are able to see their feed, access web sites, hear and tell stories from abroad and around the country. Shared access is often overlooked in connectivity studies but has been documented in India, Peru and many other countries.

Beyond shared usage, there are other, more informal methods of accessing what the web has to offer, extending through urban areas in developed countries through rural areas in the global south. Fei’s ability to navigate the city depended on the Internet—a printout from Google Maps, and then my friend's Internet connection to update it. Chances are, if she got lost again, a non-Chinese speaker with machine translation software could try to help her figure out what was going on. To call her unconnected would be to ignore the many forms of connectivity and social support around her that effectively enabled her to access data from the web. And there are countless others like her, extending across “unconnected” parts of the world.

Both informal communities in urban areas and rural locales in developing countries often feel like the edge of the Internet, where the next billion are just starting to come online. But, first, to understand the edges, it helps to understand the center and how the concept of “connectivity” is constructed.

* * *

The Internet can feel ubiquitous in both developed and developing parts of the world, but those who access the web directly are a privileged minority. For many people reading this essay, the Internet looks like a wi-fi icon in the upper right hand corner of their screen or an ethernet cable with one end plugged into a computer and another plugged into a wall. But what happens after the wall is unclear, presumed to be in the hands of professionals.

In Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet, author Andrew Blum focuses on the other side of the wall, beginning with a simple anecdote of a squirrel that chews a wire and cuts off his Internet in Brooklyn, leaving him effectively unconnected until the repair technician could come to his home. From this experience, he moves on to detail the server farms, exchange points, data engineers, and construction workers that maintain the world’s connectivity.

Despite the ridicule heaped on Senator Ted Stevens’s now infamous description of the Internet as a “series of tubes,” the Internet, Blum demonstrates, is actually filled with tubes: fiber-optic tubes, Ethernet tubes, power tubes, transatlantic tubes that mirror the telegraph cables that were strung between London and New York in the 19th century. “The undersea cables,” he writes, “showed how that new geography was traced entirely upon the outlines of the old.”

Blum reveals that the web is made not of spider's silk but miles and miles of machinery, each part built as a result of complex decisions and layers. He illustrates how the forces of geography, politics and economics combine to affect the world’s access to bandwidth:

Undersea cables link people—in rich nations, first—but the earth itself always stands in the way. To determine the route of an undersea cable requires navigating a maze of economics, geopolitics, and topography. For example, the curvature of the planet makes the shortest distance between Japan and the United States a northern arc paralleling the coast of Alaska and landing near Seattle. But Los Angeles has traditionally been the bigger producer and consumer of bandwidth, exerting a southward tug on earlier cables. With TGN-Pacific, Tyco solved the problem the expensive way, by building both.

Tubes, of course, are not the only way data travels on the Internet: The electromagnetic waves of mobile and wi-fi networks pass invisibly through us, broadcast by towers powered by electric wires or diesel. Tubes highlights how much of the Internet consists of very physical data handoffs, storage and routing, all powered by human decisions and relationships. Blum’s writing soars when his earnest fascination with this comes to the fore, as when he describes walking around New York City:

I was captivated by the idea of the light [of fiber optic cables] pulsing beneath the streets. Climbing down the steps into the subway, I’d imagine the red lights sticking out of the concrete decking. This was the municipal corollary to what was going on inside the [network] router. But it wasn’t the realm of egghead engineers, their glasses reflecting with strings of numbers. It was about thick bundles of cable and dirty streets—an even heavier reality. I started to wonder just how that light got in the ground.

Still, it can be easy to assume, after reading Blum's book, that where no tubes or electromagnetic waves flow, no Internet goes. But just outside the book’s scope, the connectivity binary begins to break down. The very story he starts with—a squirrel nibbling away at his tether to the larger world—misses the alternate ways he had to get a message out, to download movies, to access a map. He just had to ask his neighbor, assuming he couldn’t get online through his phone. And if his neighbors didn't have Internet access, they could have asked their neighbors.

Data spill forth from the tubes, carried along on USB drives or through word-of-mouth exchange, mobile Bluetooth handoffs, and “sneakernets” of data transferred hand to hand, foot by foot. If there was a sequel to Tubes, it might be called Sticks, Mouths, Teeth, and Sneakers.

* * *

In the dry season of 2013, I visited Aber and Atura, small villages tucked away between Gulu and Lira, the two largest cities in Northern Uganda, each with a population of a few hundred thousand.

Satellite photos of the region show darkness, but satellites can't capture the soft glow of a mobile phone. Many residents use their phones to text their friends and keep in touch. Mobile-phone towers dot the landscape, providing 3G Internet access to those who can afford it (a small minority) and SMS/voice access for the others (a larger minority). They power their phones at mobile charging stations set up by enterprising families who invest about $100 to $200 for a solar panel manufactured in India or China.

Nor can satellites hear the music. At night, residents turn on their radios, and those who can afford Chinese feature phones play mp3s. One day, I heard familiar lyrics:

Hey, I just met you

And this is crazy

But here's my number

So call me maybe

I turned my head. A number of young people gathered around a woman rocking out to Carly Rae Jepsen's “Call Me Maybe,” a song that owes so much of its success to the viral power of YouTube and Justin Bieber. The phone’s owner wasn't accessing it via the Internet. Rather, she had an mp3 acquired through a Bluetooth transfer with a friend.

Indeed, the song was just one of many media files I saw on people's phones: There were Chinese kung fu movies, Nigerian comedies, and Ugandan pop music. They were physically transferred, phone to phone, Bluetooth to Bluetooth, USB stick to USB stick, over hundreds of miles by an informal sneakernet of entertainment media downloaded from the Internet or burned from DVDs, bringing media that’s popular in video halls—basically, small theaters for watching DVDs—to their own villages and huts.

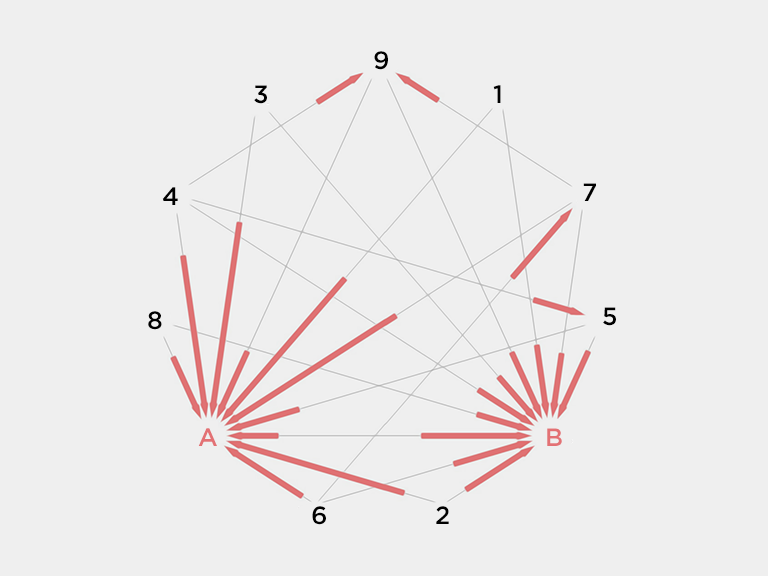

In geographic distribution charts of Carly Rae Jepsen's virality, you'd be hard pressed to find impressions from this part of the world. Nor is this sneakernet practice unique to the region. On the other end of continent, in Mali, music researcher Christopher Kirkley has documented a music trade using Bluetooth transfers that is similar to what I saw in northern Uganda. These forms of data transfer and access, though quite common, are invisible to traditional measures of connectivity and Big Data research methods. Like millions around the world with direct internet connections, young people in “unconnected” regions are participating in the great viral products of the Internet, consuming mass media files and generating and transferring their own media.

Indeed, the practice of sneakernets is global, with political consequences in countries that try to curtail Internet access. In China, I saw many activists trading media files via USB sticks to avoid stringent censorship and surveillance. As Cuba opens its borders to the world, some might be surprised that citizens have long been able to watch the latest hits from United States, as this Guardian article notes. Sneakernets also apparently extend into North Korea, where strict government policy means only a small elite have access to any sort of connectivity. According to news reports, Chinese bootleggers and South Korean democracy activists regularly smuggle media on USB sticks and DVDs across the border, which may be contributing to increasing defections, as North Korean citizens come to see how the outside world lives.

Blum imagines the Internet as a series of rivers of data crisscrossing the globe. I find it a lovely visual image whose metaphor should be extended further. Like water, the Internet is vast, familiar and seemingly ubiquitous but with extremes of unequal access. Some people have clean, unfettered and flowing data from invisible but reliable sources. Many more experience polluted and flaky sources, and they have to combine patience and filters to get the right set of data they need. Others must hike dozens of miles of paved and dirt roads to access the Internet like water from a well, ferrying it back in fits and spurts when the opportunity arises. And yet more get trickles of data here and there from friends and family, in the form of printouts, a song played on a phone's speaker, an interesting status update from Facebook relayed orally, a radio station that features stories from the Internet.

Like water from a river, data from the Internet can be scooped up and irrigated and splashed around in novel ways. Whether it’s north of the Nile in Uganda or south of Market St. in the Bay Area, policies and strategies for connecting the “unconnected” should take into account the vast spectrum of ways that people find and access data. Packets of information can be distributed via SMS and mobile 3G but also pieces of paper, USB sticks and Bluetooth. Solar-powered computer kiosks in rural areas can have simple capabilities for connecting to mobile phones’ SD cards for upload and download. Technology training courses can start with a more nuanced base level of understanding, rather than assuming zero knowledge of the basics of computing and network transfer. These are broad strokes, of course; the specifics of motivation and methods are complex and need to be studied carefully in any given instance. But the very channels that ferry entertainment media can also ferry health care information, educational material and anything else in compact enough form.

There are many maps for the world’s internet tubes and the electric wires that power them, but, like any map, they reflect an inherent bias, in this case toward a single user, binary view of connectivity. This view in turn limits our understanding of just how broad an impact the Internet has had on the world, with social, political and cultural implications that have yet to be fully explored. One critical addition to understanding the internet’s global impact is mapping the many sneakernets that crisscross the “unconnected” parts of the world. The next billion, we might find, are already navigating new cities with Google Maps, trading Korean soaps and Nigerian comedies, and rocking out to the latest hits from Carly Rae Jepsen.