This past July, Bayer announced plans to remove its permanent-birth-control product, Essure, from the U.S. market. Essure was initially hailed as an innovative alternative to cutting and tying the fallopian tubes, a process known as tubal ligation. With Essure, a doctor places a metal, coil-shaped insert in each fallopian tube to induce blockage. The result is sterilization. The product was marketed to physicians and patients as safe, over 99 percent effective, and as successful as tubal ligation without surgery, anesthesia, or a long recovery time. But for years thousands of women, known as the E-Sisters, fought against the device, the company, and the Food and Drug Administration, working to educate doctors and legislators alike on the dangers of Essure, all of which they themselves experienced: migraines, bleeding, pelvic pain, and uterus perforations. Their efforts, which resulted in the FDA issuing restrictions on the sale of Essure, have prevented many others from suffering.

Despite thousands of complaints related to Essure’s adverse effects, Bayer maintains that the device was removed because of low sales, and the FDA maintains that Essure’s benefits outweigh its risks. According to Sanket S. Dhruva, Joseph S. Ross, and Aileen M. Gariepy, doctors who completed further analysis of Bayer’s initial clinical trials, however, the company at best provided insufficient data to back their safety and efficacy claims. At worst, they presented purposely misconstrued data, and the FDA approved it. Yet Bayer, the company responsible for producing the chlorine gas used by Germany in WWI, has faced no repercussions.

How did we arrive here, where the medical-device industry has been mobilized against the patients it purportedly serves? Answering this question is the main objective of director Kirby Dick and producer Amy Ziering’s latest documentary, The Bleeding Edge. The film explores the production of several controversial medical devices as well as the failure of regulatory bodies like the FDA to control this powerful and ever growing industry. At the film’s center are the patients who are again and again sold on medical science’s latest gadget—vaginal mesh for urinary incontinence, metal-on-metal hip replacements for more active lifestyles, a robotic surgical system that shortens hospitalization and recovery time—only to find themselves the victims of consequences they were never warned about.

Take Essure for example: The film focuses on several women implanted with the device, including Angie Firmalino, who started the Facebook group that became central to the E-Sisters’ movement. Firmalino was initially swayed by Essure’s reputation as a quick procedure with a short recovery time. But she started to experience pain and bleeding immediately after the implantation. When she learned that the device had migrated from her fallopian tubes into her uterus, she opted to have it removed, but after the procedure, fragments of the device remained in her body. She was forced to undergo a hysterectomy, and later developed an autoimmune condition. For every story like Firmalino’s, there exists a physician who seems blissfully unaware that adverse effects are even possible, and a manufacturer who receives complaints with skepticism.

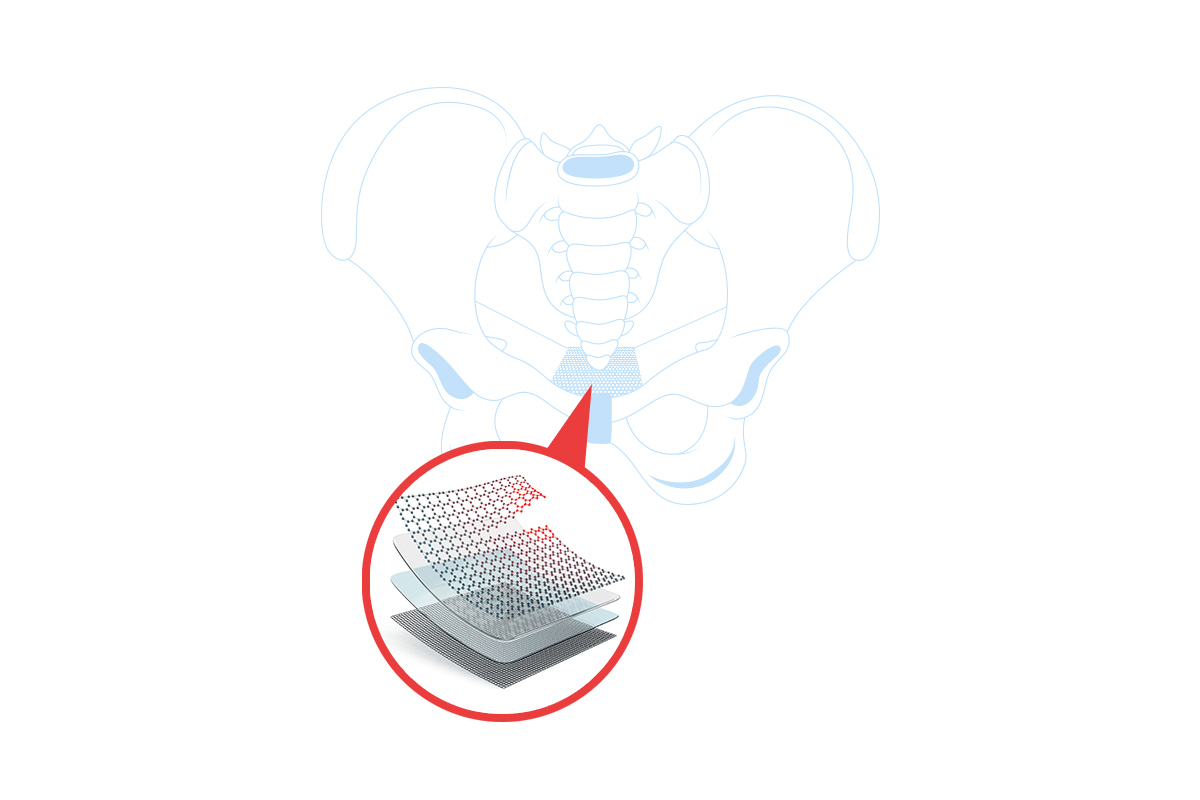

Tammy Jackson, a woman who, at the suggestion of her doctor, attempted to treat her urinary incontinence with pelvic mesh, shares a similar story. At the time, Johnson & Johnson’s mesh, an artificial material permanently implanted to augment vaginal tissue repairs, was advertised as superior to older surgical techniques that rely on suturing native tissue into place. But the mesh immediately caused Jackson pain and discomfort, leading to a cascade of surgeries not only to remove the mesh but to treat new problems—severe fatigue, pain during sex, and kidney atrophy—caused by its implantation.

How did such risky devices make it on the market to begin with? The Bleeding Edge reveals that 98 percent of medical devices receive approval via the FDA’s 510(k) process, through which a company must only prove that its device is substantially equivalent to an existing legally marketed device. For an estimated 90 percent of 510(k)-approved devices, such as metal-on-metal hip implants and vaginal mesh, the company is not required to submit clinical-trial data proving safety and efficacy. In fact, through the film we learn that the company Johnson & Johnson pursued 510(k) approval for vaginal mesh despite being warned by researchers that it was unsafe. Johnson & Johnson’s unethical behavior is not a rare occurrence: A five-year review of FDA recalls for high-risk medical devices found that 71 percent were approved via the 510(k) process. Seeking approval while ignorant of or willfully ignoring the risks of a so-called innovative device is routine; even the most rigorous process used for device evaluation is utterly inadequate. Through premarket approval (PMA), companies must demonstrative safety and efficacy via a single study.

It should be no surprise that the FDA failed to prevent such poorly studied devices like Essure from making their way to market. For years, the FDA has been critiqued for its inability to safeguard consumers from another major player in the medical industry: Pharmaceutical companies. Though pharmaceutical drugs are subjected to a more stringent vetting process than medical devices, companies often falsify data. Pharma’s abuses demonstrate a need for greater oversight in the medical industry, yet the FDA’s actions have been to deregulate medical devices rather than correct. In fact, in 1976 when medical devices first fell under the FDA's jurisdiction, the 510(k) was only intended as a minor exceptions process during the transition, but after FDA reinterpretations and alterations in 1990 and 1997 it has become the main pathway for medical-device approval. Still, one might wonder why a company would risk lawsuits by putting an ineffective medical device on the market. Again, practices in the pharmaceutical industry are instructive: The costs associated with lawsuits are nothing compared to the years of profit.

Physicians and other medical professionals have proved themselves to be poor gatekeepers for medical care. According to The Bleeding Edge, even the most well-meaning physicians have an obsession with cutting-edge technology. These doctors tend to flock to the newest gadget and defend its benefits at all costs—even, in some cases, against patients who are privy to their adverse effects. This tendency to trust a device simply because it is FDA-approved over patient experience becomes even more problematic when considering that most physicians don’t seem to understand how the FDA’s approval process works. They assume that approval—a process that is largely figurative, having more to do with a company’s ability to game the system than with its ability to provide effective treatment—speaks to a drug’s safety and efficacy. The Bleeding Edge reveals that many medical professionals are unaware, even, that devices can reach the market without undergoing a single clinical trial.

The Bleeding Edge ends with a series of safety precautions, intended to help viewers become better consumers. For some this will likely be the film’s main takeaway: A story about the failures of regulation and the untrustworthiness of providers, companies, and the FDA could only mean that we must become more cunning patients. Others may suggest that FDA reform is necessary to bring the industry in order. Both of these perspectives have merit. To a large extent, we already consume health care as a commodity, whether by using Physician Compare tools to choose providers, or purchasing insurance via the federal Marketplace. These exchanges are unlikely to be phased out anytime soon, so we should promote practices that ensure safe and successful access to healthcare. Regulatory bodies, moreover, should exist in any marketplace to ensure that certain standards are maintained.

But it seems to me that the true message of the film is revealed in some of its most minor moments. At the start of the movie we see the CEO of AdvaMed, the leading lobbyist organization for medical-device companies, giving a speech about the innovative power of the medical-device industry. “Or what if artificial intelligence can be used to predict heart attacks before they even happen? If we succeed, imagine the impact we will have on medical care. Let’s continue to improve lives by unleashing innovation.” Later, we are shown a clip of an FDA public-service announcement from 1950 about fraudulent devices, like the “Zerret Applicator,” which purportedly cured arthritis with “z-rays,” or a tape recorder able to cure cancer with music. The PSA warns that these devices are no better than miracle elixirs and snake oils. More heady speeches by company executives follow later in the film, emphasizing the grand future that awaits us thanks to advancing technology. The implication is clear: These so-called innovators are the new con men. While their peddling has far surpassed that of their predecessors, they are still driven by financial gain, not lofty visions of life-saving innovations.

Certainly, there are medical devices on the market that are vital for many patients, like portable oxygen concentrators and pacemakers. But the actions of major corporations like Bayer and Johnson & Johnson demonstrate a willingness to abandon or misconstrue the results of evidence-based science for money. It’s ironic how often these companies make the case for needing to make greater profits to recoup research and design costs and reinvest resources in new research when they are cutting corners and attempting to spend as little money gathering clinical data as possible. Just as in the past, the end goal is not the miracle cure but its sale.

To begin to remedy this issue, medical-device research needs patient-centered principles to guide innovation. Research should be driven by patient needs and lead to meaningfully different products. Currently, the 510(k) process effectively incentivizes companies to make minor design changes to preexisting products and focus their efforts on finding a new marketing angle. Instead of using a traditional ceramic-on-plastic hip implant, get the durable, new metal-on-metal implant advertised better for individuals with more active lifestyles. At worst these minor design changes may lead to major adverse health effects, such as the metal poisoning reportedly caused by metal-on-metal implants. People should be at the center of medicine, and the 510(k) process is incompatible with any future where they finally are.

However, it is not enough to demand patient-centeredness when a majority of the research is funded by companies willing to risk the lives and well-being of patients for financial gain. To truly reform the medical-device industry, we need to remove the incentive to peddle false innovations. The income-driven industry must be abolished. As long as greed is the bottom line, medical-device companies will seek approval for technology that is unsafe or ineffective.

Of course, industry executives will respond that without financial incentive, there will be no innovation. They will threaten stagnation, predict an end to years of progress. In truth, the individuals trying to do real research today are having their efforts stifled by a perverse ethos: Data only matters when it matches the marketing message. There will always be those willing to do the work; imagine what our medical system would look like if they stood at its forefront.