The Land of Nod is perhaps the last commons left to us, but capitalism has awoken to the idea of enclosing it

In 2004, The UK's Channel 4 recruited five men and five women for a novel game. Whoever resisted sleep the longest would win a cash prize.

Their struggles were made subject of a television series appropriately titled Shattered. Each night thousands across Britain tuned in to watch contestants, zombified from lack of sleep, perform memory exams and other tests of mental agility. Every so often, they were asked to endure an hour-long "You Snooze You Lose" challenge, in which they had to resist the soporific effects of massage, giant teddy bears, bedtime stories repeated ad nauseam, watching coats of paint dry, counting sheep on television and, perhaps the biggest challenge of all, listening to a lecture on trigonometry. The show's website allowed viewers to keep track of the contestants' sleepiness and performance. Almost all the contestants suffered from the usual symptoms of sleep deprivation, including hallucinations. One contestant believed herself in a subway station. Another fancied himself the Prime Minister of Australia.

The final episode saw the contestants ushered to a plush bed. The last to resist its comforts won the cash prize. The winner, a female police officer trainee, nodded off after an epic 179 sleepless hours. Her fortitude she attributed to certain small tricks, such as tensing her feet until they hurt and preventing herself from urinating. Her exertions netted her £97,000.

You could say that a show like Shattered was inevitable. Reality television's undying appeal forces producers and show creators to leave no corner of culture unlit. Grungy restaurants, trashy housewives, inbred pageant queens: all is fish as swims in their net. But like most mass entertainment, Shattered performed a good deal of ideological work as it did its part to keep the airwaves filled. The clumsy antics of ten sleepless Brits did more than amuse. They modeled, however imperfectly, defiance of the body's most primal imperatives. What's more, the reward for such defiance was no mere thrill at seeing mind prevail over matter. It was cold, hard cash. That this ordeal took a terrible toll -- "What we are doing is putting people's health at risk and causing them psychological harm," a psychologist said when asked to opine on the show -- apparently failed to trouble producers. They no doubt understood that, whatever the consequences for the contestants, troubled sleep made great viewing.

Troubled sleep is the subject of theorist Jonathan Crary's latest book, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. It presents a world in which everything is illuminated and everyone is up all night. Any time that is not "work time, consumption time, or marketing time" loses relevance, as benumbed citizens assimilate "an every-expanding surfeit of services, images, procedures, chemicals, to a toxic and often fatal threshold," and assent to "permanent expenditure," "endless wastefulness," and "terminal disruption of the cycles and seasons on which ecological integrity depends." And they do so without regard to distinctions "between day and night, between light and dark, between action and repose." Their social identities "reorganized to conform to the uninterrupted operation of markets, information networks, and systems," they find their bodies removed from "the rhythmic oscillations of solar light and darkness, activity and rest, of work and recuperation." Time loses any sense of movement once subject to 24/7's ideological modulations. Life within this regime becomes a relentless marching in place. Arriving nowhere, the march proceeds to the tune piped by the usual suspects: the plutocratic elite. Only their impulse for pure profit extraction enjoys free play under the conditions Crary analyzes. You could say 24/7 truly is the One Percent's lucky number.

Only the most intractable of biological functions resist 24/7's existential kettling. "The huge portion of our lives that we spend asleep, freed from a morass of simulated needs," writes Crary, "subsists as one of the great human affronts to the voraciousness of contemporary capitalism." Why an affront? Because as far as sleep is concerned, the "stunning, inconceivable reality is that nothing of value can be extracted from it." So vexing is this problem to technocrats, warmongers, and financiers alike that the U.S. military is attempting to develop a "sleepless soldier," an insomniac drone big business hopes will be the forerunner of "the sleepless worker or consumer."

Military research into sleep reduction signals a reemergence of the human, albeit in terms altogether opposite from its earlier appearance on the world's stage. During the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, to be human was to be a creature in possession of powers, talents, and abilities nowhere evident in the rest of Creation. Under 24/7 conditions, however, the word "human" suggests deficiencies, frailties, incapacities. To be human now is to inconvenience the otherwise smooth and efficient development of the perfect societal machine. Wayward but at the same time indispensable, humans stand in need of an upgrade if this machine is to realize its promise.

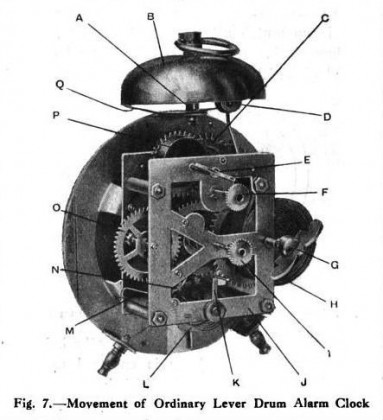

The military has its work cut out for it. Crary writes that 24/7 denotes an "impossible temporality" that, as such, places impossible demands on individuals. Its exhortation to permanent sleeplessness certainly demands the impossible. Too little sleep leaves you groggy and prickly; none at all eventually leaves you dead. Sleep researcher Alan Rechtschaffen and colleagues' sleep-deprivation experiments on a rat confirmed this long held suspicion. In the 1960s Rechtschaffen and his researchers positioned the animal on a turntable measuring 46 centimeters in diameter and mounted on a spindle. Under the turntable they placed a shallow tray of water. Electrodes inserted in the rat's brain connected to a computer that monitored its brainwaves for any sign of sleepiness. Each time the computer sensed the rat had grown groggy, it caused the turntable to rotate. This forced the rat to rouse itself lest it receive a dunking. After a sleepless week, the animal's paws erupted in ulcers. Its fur became thin and matted, no matter how assiduously it groomed itself. Though the rat gorged on kibble, its body wasted. Its temperature fluctuated, and its immune function waned. Three weeks into the experiment, Rechtschaffen's sleep-deprived rat died.

Sleep-deprived humans don't fare much better. Irritability, depression, emotional volatility, and, eventually, hallucinations plague the insomniac. Charles Lindbergh experienced the gritty discomfort of sleep deprivation during his first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight in 1927. His 33 hours without sleep brought him nearer to disaster than did any mechanical malfunction or patch of rough weather. The night before his pre-dawn departure, Lindbergh was anxious. He slept fitfully, later recalling in his memoir that he grabbed two, maybe three hours rest before reporting to Roosevelt Field, his place of departure. Warm inside his flight jacket and lulled by the dull hum of his plane's engines and an empty expanse of blue sky, Lindbergh felt an irresistible drowsiness come over him only a few hours after takeoff. "My eyes feel dry and hard as stones," he recorded in his flight log. "Keeping them open is like holding arms outstretched without support." He complained of having little control over his body, and said his mind "clicks on and off, as though attached to an electric switch with which some outside force is tampering." He knew that to surrender to his drowsiness, even for an instant, would spell disaster, but his body had its own ideas: "[It] argues dully that nothing, nothing life can attain, is quite so desirable as sleep."

The need for sleep is not purely biological. Prehistoric man, who passed his days hunting and gathering, dozed for as long as fourteen hours at a stretch, drifting in and out of dreams. Many of those hours he spent not necessarily sleeping but reflecting on the contents of those dreams. Mammoths, tigers, cave bears, and perhaps occasionally creatures altogether more appealing captured his mind's eye like so many shadows thrown by firelight upon a cave wall. What he made of these visions time has left to our imagination, but they likely inspired musings about his place in the world.

24/7 conditions render a place in the world altogether unattainable. They induce, rather, a sense of "worldlessness," as Crary puts it, refashioning the existing world into one that is "identical with itself" and possessed of "the shallowest of histories." Worldlessness in turn gives rise to a lack of "situatedness," that is, to a constant upheaval whose friendlier (though only barely so) gloss is "disruption," constant technological change to which humanity must forever catch up. In its totality, 24/7 confronts individuals as a monumental indifference, against which, Crary observes, "the fragility of human life is increasingly inadequate." This becomes all the more apparent as the imperative to consume mounts "a relentless incursion of the non-time of 24/7 into every aspect of social or personal life." The net effect is that "one inhabits a world in which long-standing notions of shared experience atrophy." With little left to turn to account, 24/7 capitalism looks to exploit those things we see as fundamental to our humanity. That the assault on sleep happens to coincide with the assault on social relations, public institutions, and the environment is merely to be expected. An economy intent on exhausting people has already exhausted everything else.

Two aspects define the 24/7 zeitgeist. The first traces its history to the 19th century, and its significant figures are the inventor industrialists of that period. (Crary names Thomas Edison, George Eastman, and Wilhelm Siemens as examples.) The second aspect is of more recent stamp. Its genesis is rooted in the information revolution of the 1990s, and its emblems tend to be companies themselves rather than those who founded them. (According to Crary, these include Microsoft, Google, and the like.) In an important sense, then, 24/7 involves structures of dominance in place for well over a century. Its flashy digital trappings simply bespeak of the necessary modifications these structures needed to undergo in order to adapt themselves to evolving cultural forms and practices. The rising and setting sun 24/7 seeks to blot from consciousness, if only to obscure the fact that there's nothing new under it.

Redacted to its essence, 24/7 is an emanation of the capitalist's imperishable desideratum, surplus value. The designation enjoys the virtue of articulating in a single ideologeme surplus value's two characteristic forms: absolute and relative. Absolute because it seeks to push one working day against the next without interruption; relative because it seeks to intensify the alienable engagement of every individual at nearly every conceivable measure of time. This tendency remains somewhat hidden by the fact that the ascendant idea of labor has taken on largely immaterial forms -- the manipulation of signs, most notably, as well as the production and management of affects -- and that the sites at which these new forms of labor take place are quite literally everywhere. The shop floor has attenuated and expanded to encompass the entire social field. Hence 24/7's utter dependence on the erosion of distinctions obtaining between work and leisure.

Negated is the utopian dream of a future predicated on abundance and ease. Erected in its stead is a nightmare vision of ruthless, zero-sum competition. Culture distinguishes itself from nature only to lapse into a techno-virtual simulacrum of the latter, as remorseless as it is absurd. The Orwellian–Huxleyan aura surrounding 24/7's characteristic technology is neither an accident nor something projected onto it by Chicken Littles. This aura is essential to it -- indeed, decisively so. Technology serves the single aim of seizing the reins of power for those who file the patents, write the licensing agreements, or hold the debt notes. The many subjectivities hollowed out and bodies rendered docile by the latest iThis-or-That testify to this single, undeniable fact.

We tell ourselves that the tide will turn, for surely it must when so many are exploited and so much has been destroyed. But the truth remains that complicity in 24/7 is baked into the cake of modern living. Its various apps and gizmos, then, may never be personalized in any meaningful sense. According to Crary, emancipatory politics cannot be enacted through the very devices and social media (smartphones, Twitter) that make us think such change is nigh. Those who, for moral or intellectual reasons, happen to oppose 24/7 hegemony find themselves the unwitting loyal opposition. Sad dupes, they become "the product of the media apparatus in which they are captured," Crary writes, no matter how much they struggle against their bonds. Meanwhile, those who refuse to consume the steady surfeit of doo-dads that slouch towards obsolescence even before they hit store shelves 24/7 positions as Luddites ripe for dismissal or ridicule.

A closed system brooks no resistance. Yet, though 24/7 draws its net ever tighter, some of the old world squeezes through the webbing. At least for now, we can still dream of "a shared world whose fate is not terminal," Crary writes, "a world without billionaires, which has a future other than barbarism or the post-human." Crary makes a smart argument, one which would perhaps find wider purchase if it didn't display the excesses typical of much academic criticism. And such astute and far-seeing observations as those contained in 24/7 ought to find wider purchase. For once 24/7 does dispel the darkness and fling open the curtains, history ends -- with neither a bang nor a whimper, but a yawn.