We begin the story again, as always, in the wake of her disappearance

and with the wild hope that our efforts can return her to the world.

—Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”

As young black women, we shouldn’t have to look behind our back you know,

we should be living freely like everybody else.

— Letifah Wilson

Twelve hours after Nia Wilson was stabbed to death by a white man on the MacArthur BART platform in Oakland, Maya texted me, saying she was “super panicky” and didn’t think she could make it to work.

Maya—my firstborn, 18, beautiful, awesomely caustic, the smartest one in the house—had been diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder earlier in the summer, not long after returning home from her first year at college. She was always an anxious kid, and spending the year building a new life so far from home had left her unsure in her own skin, about her place in the world. She had become prone to panic attacks; nothing scared her more than the sound of her own heartbeat in the quiet and stillness of summer break. We spent June through August taking trips to the health-care provider and to therapy, having regular conversations about getting to and through work, checking in about meds, making weak attempts at meditating, and sending steady streams of “check-in” texts. I had just come out of my own therapy and was slowly making my way home when I read Maya’s text. Emotionally raw and undercaffeinated, I deflected to her father.

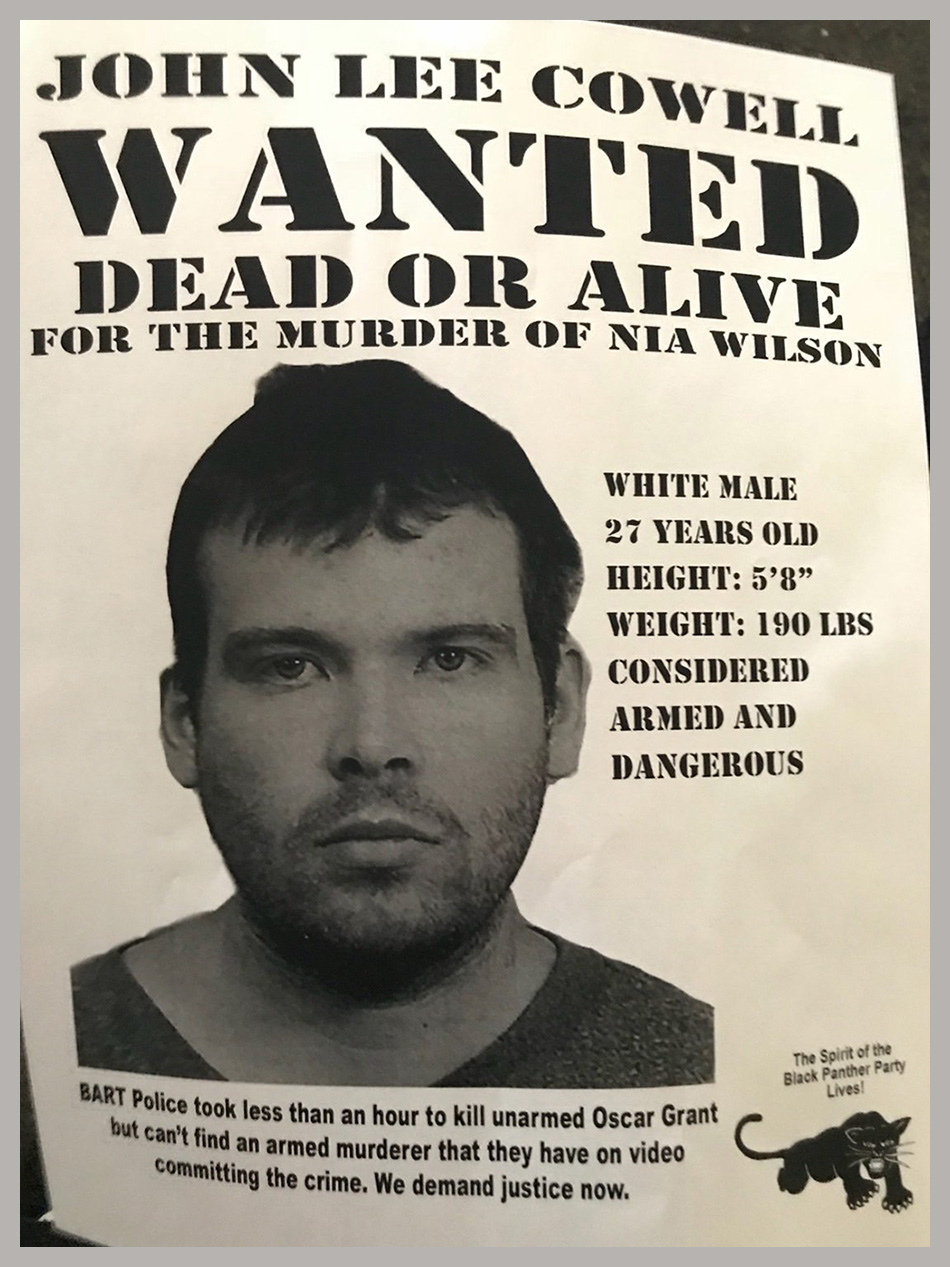

Michael Mark Cohen, John Lee Cowell "Wanted: Dead or Alive" poster, July 22, 2018

Michael Mark Cohen, John Lee Cowell "Wanted: Dead or Alive" poster, July 22, 2018It is weird and also wrong—that is, inappropriate, self-serving, maybe even a bait and switch—to start a piece about an 18-year-old black girl from Oakland named Nia Wilson who was murdered by a white man as she and her sisters transferred trains at MacArthur BART station with the story of a black girl named Maya Raiford-Cohen from Berkeley who suffered a panic attack because she would have to ride BART and transfer trains at MacArthur station 12 hours after Nia Wilson died in her sister’s arms. But I have tried to start this many ways, and it always begins here: with an 18-year-old black girl in danger.

My own false starts and stutter steps are not dissimilar to the problematic Saidiya Hartman turned over and over in her 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts,” which is about the dangers of recounting black female lives in precarity: How can you write the story of black girls already caught up in narratives pre-scripted by the state? Is it hubris to think that our retelling, my feeble attempts at narration, might rescue these girls from the repetition of a violent life and a violent death, might return Nia to the world (and Maya to herself), might constitute a practice of freedom?

#AreBlkWimminSafeHere

A few minutes before he stabbed Nia Wilson and her sister Letifah and then made his way across 40th Street to change his clothes, John Lee Cowell was just another white man on the MacArthur BART.

MacArthur station is a crossroads, an exchange point, and a key pass-through for the East Bay. It is a transit station significant for its encapsulation of quotidian East Bay life, which is in constant transformation. As one of two designated timed-transfer stations, where different train lines wait for each other across the platform to facilitate passenger connections and ease transit flow, MacArthur BART is the stage for choreographed convergence. In these specified 60-second windows, you can see who’s going to work in the city, who’s headed to private school through the hills, who’s making their way to SFO, who’s trying to get to Oracle Arena, and who is just trying to get home safe.

MacArthur BART is between the West Oakland station—the last stop before the BART descends under the Bay to San Francisco, and the first stop of gentrification begun in the wake of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake—and East Oakland’s Fruitvale station, where Oscar Grant was murdered by white BART policeman Johannes Mehserle in 2009, and where Oakland’s reputation as protest hotbed was subsequently reignited and reaffirmed. MacArthur is the station Oakland and much of the East Bay passes through: those coming from the suburbs through the tunnel, and those coming from the ghettos to the north and east through the transitioning yet rapidly gentrifying Longfellow section of North Oakland. Longfellow, along with wealthier and self-satisfied Rockridge, was once part of a larger neighborhood, Temescal, before the Grove Shafter Freeway came and erected a formal and visible distinction between “us” and “them.” The area around MacArthur station remains a wide no-man’s-land, in part because the aboveground BART tracks and the highway cast deep shadows across a bifurcated MLK Way.

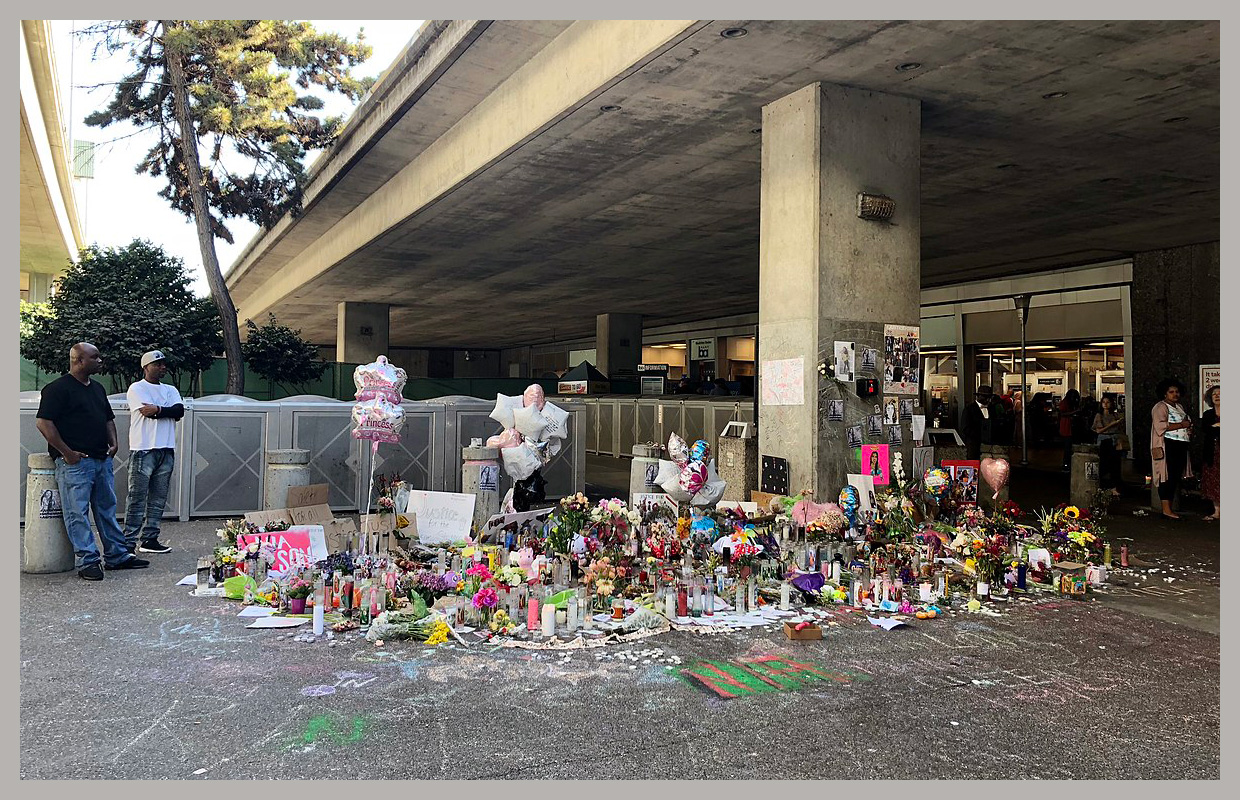

This geography was evident at the multiracial intergenerational rally organized in response to Nia Wilson’s murder. Maya and I got off at MacArthur, a stop before home, because we needed to stand with and in community to reclaim this space. Black folks in the Bay those last few months pulled taut by BBQ Beckys and Permit Pattys had responded by reclaiming public space, both physical and virtual — black Twitter does not play — asserting their right, to borrow from Paul Gilroy, to be seen to be free even when we’re not, and trying to put a few days back on life spans shortened by systemic racism. But tonight there was intense grief, little humor, and calls for vigilante violence. We were undone.

Nia Wilson was present at the center and margins of the vigil. Pictures of her were on the speakers’ platform, in the altar, on a few scattered signs hastily affixed to the walls of the station. Some people knew and loved her; some people knew and loved black girls like her. But something else ran through the veins of the rally. Maybe it was the unhelpful call to black men to be men and protect (their) women. Or maybe it was the conflicting invocations both to be disciplined and to burn shit down. Really it was exhaustion, I think. And not having all the facts but still knowing what had happened.

Maya and I headed home once the speeches were done and the crowd turned to march down to Frank Ogawa / Oscar Grant Plaza. They would meet up and converge with a Rally Against Hate (to counter a rally of white supremacists) planned well in advance of Nia Wilson’s murder.

#WhiteSupremacy #WhiteSupremacist #Antiblackness

The morning after Nia Wilson bled to death encircled by her wounded sister and first responders, BART police still had no information to offer about the suspect beyond the description that Wilson’s sisters Letifah and Tashiya had provided and what was gleaned from a couple of surveillance-video stills. This lack of information allowed for other narratives—some conspiratorial—to fill an increasingly anxious absence. We knew he was a youngish, heavyish white man. And that he followed the three young women off the train.

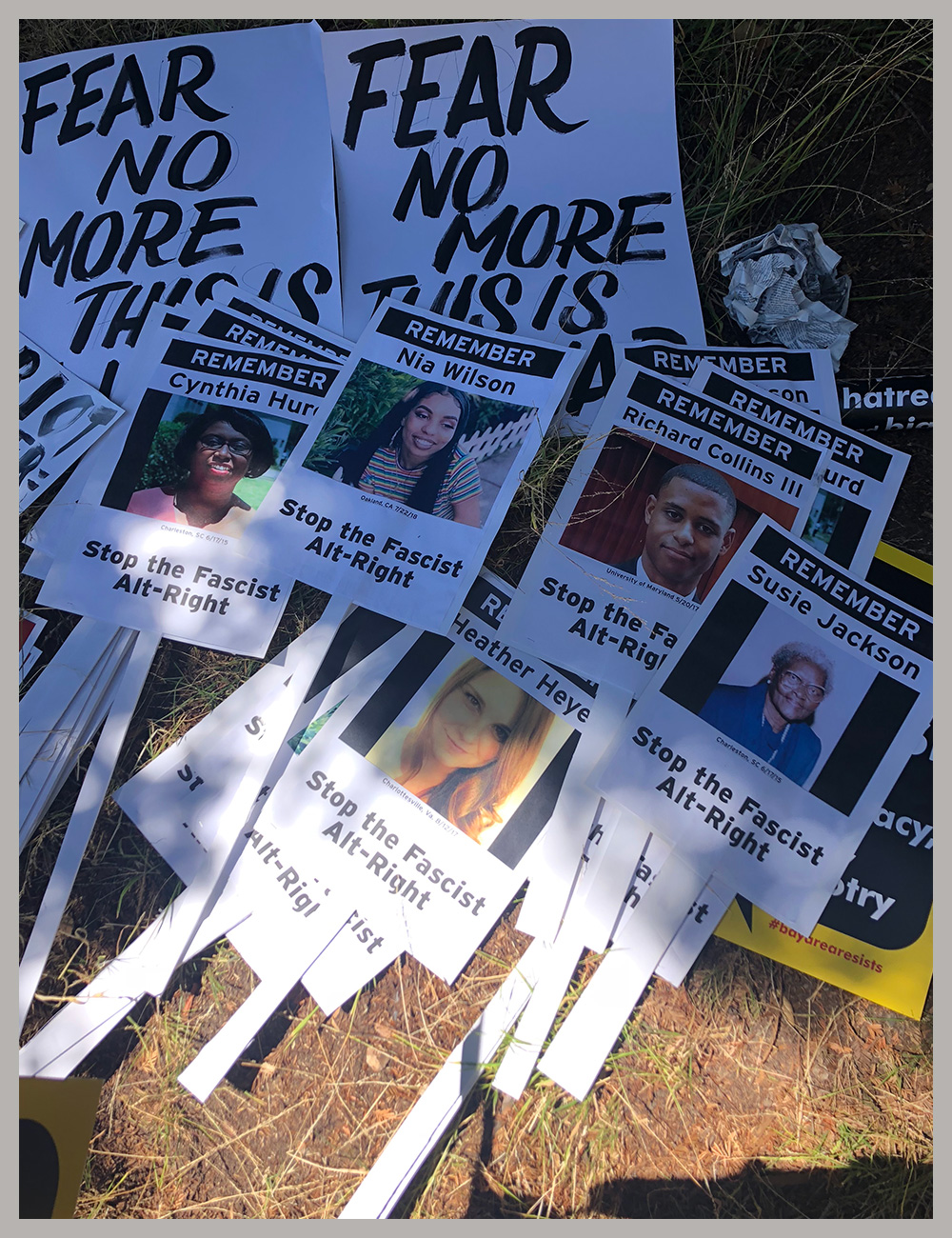

The previously planned rally of white supremacists lead to the circulation that the man who murdered Nia Wilson was himself a white supremacist. As far as we know, Nia Wilson’s murderer was not planning to attend the rally, nor was he an official member of any white-supremacist organization. It turns out he really was just a “mentally ill lone wolf,” a “bad apple” who committed a “random and senseless act,” or any of the other platitudes employed by press and politicians that effectively individualize white men and isolate them from histories of violence. That a white man murders a young black woman and wounds another after dark on a train platform on the eve of a rally of white supremacists in a city that will punch a Nazi or Internet-shame a racist without thinking twice, however, hardly seems coincidental. There is nothing coincidental about black death. The white man who murdered Nia Wilson, almost murdered Letifah, and left Tashiya to watch didn’t have to be a self-identified white supremacist for his crime to be underscored , motivated, and normalized by antiblackness.

What does it mean to suggest that “random” roams around in the space between white supremacism and antiblackness? Tethered together (not unlike the neighborhoods of Rockridge and Longfellow), white supremacy and antiblackness are each concerned with the structures and ideologies that maintain matrices of racialized domination. Yet whereas white supremacy is the toxic and desperate belief in the superiority of white people, antiblackness is concerned with the systems and practices that specifically target black people—marginalizing, oppressing, and rendering them vulnerable to premature death.

To name Nia Wilson’s murder the act of a white supremacist is in a sense to center John Lee Cowell as the protagonist of this story. And I’m sure one day some mainstream journalist will write that story. Recognizing the distinction between white supremacy and antiblackness, on the other hand, is to insist on not overshadowing the vulnerability of Nia, Letifah, and Tashiya Wilson as black women. It is to acknowledge that Nia Wilson’s life both had value and also was spent navigating seen and unseen dangers before her death. Identifying her murderer as a white supremacist lends her death a visibility that is also an erasure of her life. When black people appear in official records as merely a sum of deaths, through abstractions and statistics, there is a sense that our living does not matter. Nia Wilson’s appearance and our rallying around her death was amplified and made legible by the mis/naming of this as the crime of a white supremacist.

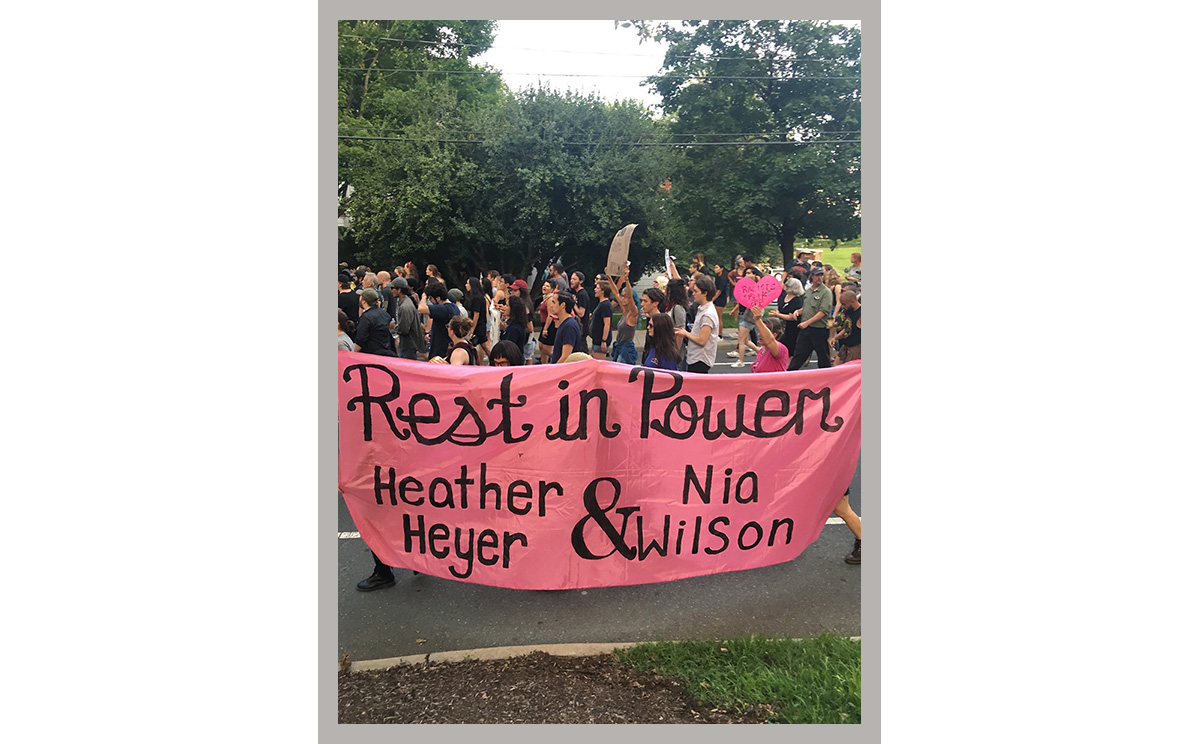

Michael Mark Cohen, “Stop the Hate” rally, Berkeley, CA, August 5, 2018

The signs that appeared at the one-year commemoration of the violence at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and at the local anti-fascist rally here in Berkeley, cemented this connection: “Rest in Power Heather & Nia.” What is the continuity between the explicit martyrdom of Heather Heyer—who at 32 had lived an activist life, knowingly entered a combat zone, and was killed in Charlottesville in 2017—and Nia Wilson, who’d only just begun to live an adult life and was merely making her way home? One volunteered for service and the other was conscripted. How and why are they both claimed by the Movement?

The distinction is this: One was killed by a white supremacist, the other killed by white supremacy. In the same week that Nia Wilson was stabbed to death transferring trains at MacArthur, another black woman died on BART. Jessica St. Louis had been released from Santa Rita Jail on July 28 at 1:30 a.m. and had to travel the 1.8 miles to the Dublin/Pleasanton BART station (the last stop on a line that doesn’t pass through MacArthur) on foot. She was found dead a few hours later. I only know Jessica St. Louis’s name because it was mentioned in one of the many articles I read about Nia Wilson. And when it seemed that Jessica St. Louis likely died of a drug overdose, #JessicaStLouis became tethered to #NiaWilson by those interested in fighting for how black women’s lives are made disposable by interlocking systems of oppression, in this case the Alameda County jail’s late-night release policy. My point is that Jessica St. Louis’s death yielded no memorials. Antiblackness is banal; it’s hard to know how to commemorate unspectacular loss.

This distinction between a spectacularly knowable white supremacy and the quotidianness of antiblackness started to grind me down. It rendered me raw and made it so I became increasingly unsure how to read my everyday world. I realized that I couldn’t talk to my husband for more than a week because of his first text to me, which said that Nia Wilson was “murdered by some white supremacist,” misnaming Nia Wilson’s murder as the crime of the Proud Boys, as if it were Milo Yiannopoulos or Ann Coulter who’d plunged a knife into her throat. Always one for direct action, my husband insisted that a march against, or a street brawl with, 4chan would make our streets safe again. It was a naivete that smelled of arrogance, born of his own sense of helplessness maybe and desire for narrative movement that would bend the arc of the moral universe more closely and quickly to justice.

Me, I was stuck. Fighting white supremacists and white supremacy — always necessary — wasn’t going to make black women’s lives less expendable to the state or less vulnerable to “random” acts of violence. It wasn’t going to redirect the solution away from more police as the BART “Customer Satisfaction” survey Maya and I took that day kept insisting, with its questions about “addressing homelessness” and providing adequate police presence. In the days after Nia Wilson drowned in her own blood, nothing could make us feel safe. My husband and I took turns riding the BART with Maya for the next few days to and from work.

#SayHerName

Nia Wilson, November 10, 1999 – July 22, 2018 (Instagram, multiple news outlets)

Nia Wilson attended Oakland Tech and graduated from Dewey Academy. People who knew her said she was kind and loving. Whether you knew her or not, anyone could see she was beautiful. And her skill with makeup artistry made her everyday around-the-way-girl pretty even more captivating. She was making plans for her future and different sources claim different directions: She was an aspiring rapper, she was going into the military, she wanted to be a paramedic, open a dance school, have her own makeup line. She had a big job interview scheduled that she never made it to. It’s all a kind of openness to uncertainty and unknowing befitting an 18-year-old.

Two years ago, Nia Wilson lost a boyfriend who drowned accidentally. And at a memorial service for him, shots were fired. Another black girl, Reggin’a Jeffries, was hit by a bullet and died in Nia’s arms. Writer Doreen St. Félix reminds us how Nia’s short life was entangled in state bullshit. Or to borrow from Christina Sharpe, it was a life lived in the hold. But/and Nia Wilson’s life was one of beauty and experimentation, one held in community, and sonorous with love. Sometimes in the telling, we forget that joy and trauma can and do live in the same place.

For Nia Wilson’s family, and for other loved ones left behind in the wake of deaths that are at once political and personal, the terrain of the postmortem hashtag can be unsteady, and navigating it can prove delicate. In public statements and Instagram posts, Wilson’s sister seems to vacillate between wanting her sister to not be forgotten (through the use of the hashtag) and not being able to dictate the terms of that memory (“she is not a hashtag”).

We know not so much about Nia Wilson but plenty from her own social-media presence — which we have to take seriously, not in the bullshit way the media does as a cherry-picking judge and jury of a victim’s worthiness, but because these are Nia Wilson’s fashionings of self. “Nia,” which means purpose in Swahili (the sixth day of Kwanzaa), is maybe new to us, made known by the hashtag that now precedes Purpose, a word and name that takes on new meaning and reinhabits original intentions. But Nia was not new to herself. Or rather we have to take seriously how she made herself anew with each selfie, with each filter applied, with each deep knee pose, with each angle hit and slice of light found. We can pay attention to the way she looks at herself, and can begin to know her.

#NiaWilson

Josh Begley, “15,000 ways of remembering Nia Wilson, as seen on the hashtag in her name” (Instagram), August 3, 2018; image courtesy of the artist

Truth be told, I hated his aggregate. Fifteen thousand fucking pixels that told me more about Internet users’ lazy penchant for repetition and inability to find anything original than it did about Nia Wilson. I hated it because in the end there was nothing to see but indistinguishable grief, each square the same size, as if everyone’s grief measured exactly the same amount, as if loss were quantifiable. Just because we’re all here, dance scholar Jasmine Elizabeth Johnson has written, doesn’t mean we’re together.

A week later, I was still confronted with the problem of telling this story, one version of which is this: black girls struggling against multiple forms of erasure while also asserting—dancing, reveling in—opacity.

Kenyatta

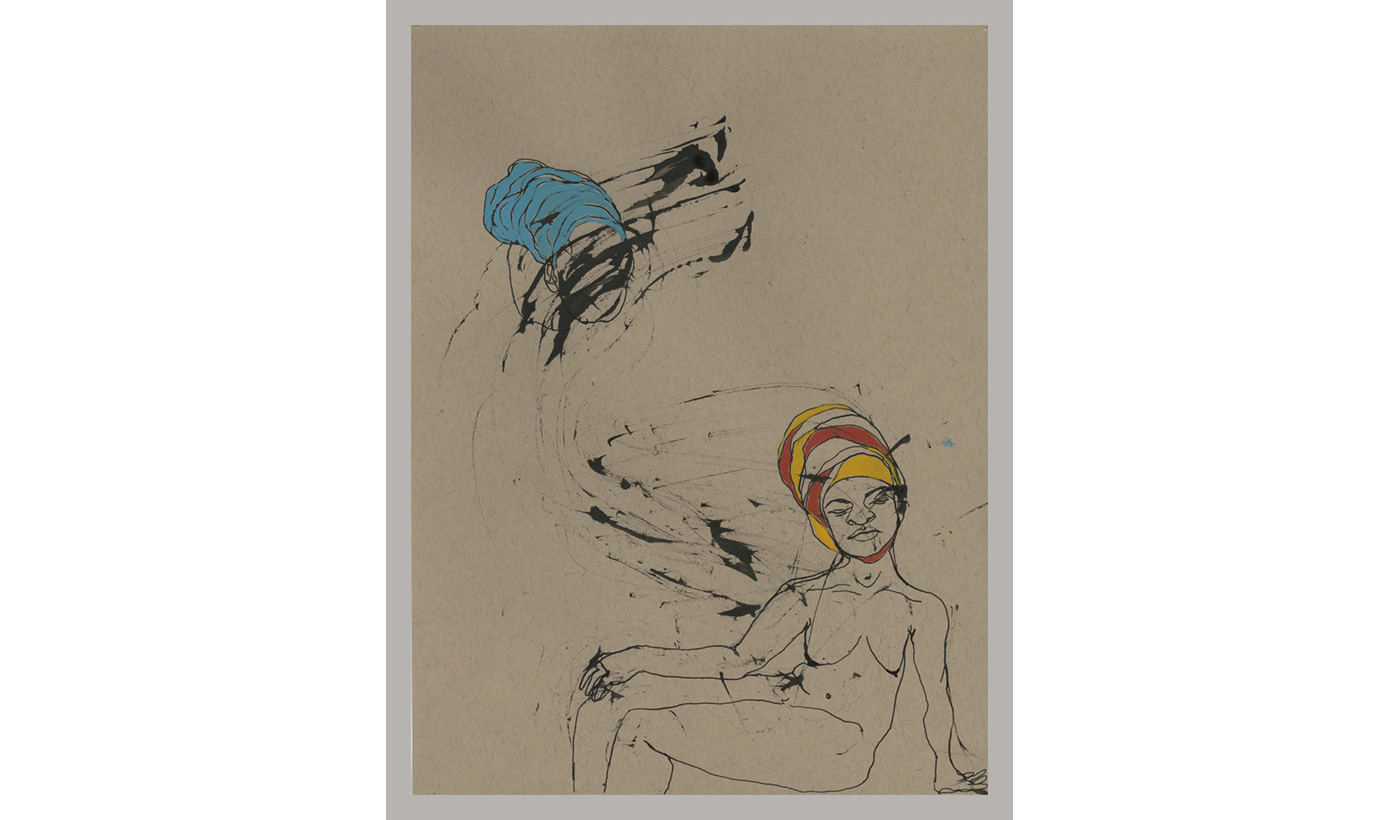

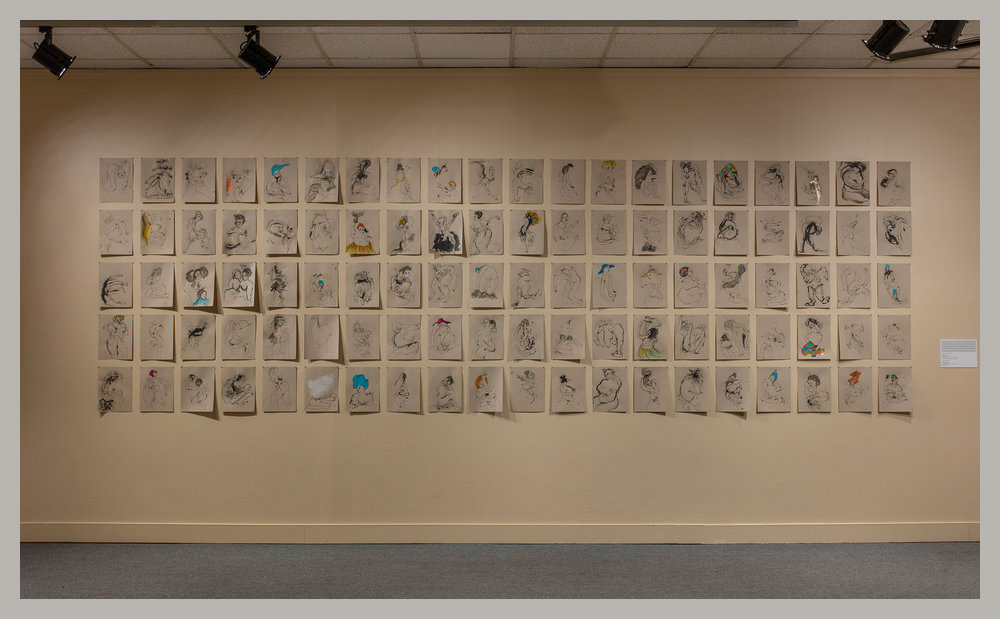

A. C. Hinkle began her series The Evanesced in 2016 with 100 india-ink and watercolor paintings of black women disappeared and disposed of, disregarded, discounted, controlled, confined, and left for dead, whether by physical violence, psychological abuse, cultural erasure, or social death. In each press account the inspiration for the series is recounted a little differently: the crisis of missing girls in Washington DC, or the “Grim Sleeper” serial killer in LA, or sex trafficking, or all the ways we abandon or “ghost” black women, as Hinkle puts it. There is space here in The Evanesced for Nia Wilson and Jessica St. Louis, for Diamond Stephens and Sandra Bland. And when I stand in front of these women, following their lines and listening to how they take up space on their page, there is room as well for me, and for the black women who have held me in community and for the black women I don’t know who I pass when I transfer trains at MacArthur. And so too there’s space for Maya, who was reminded so acutely of black women’s vulnerability when Nia Wilson was murdered that she forgot how to breathe.

Hinkle doesn’t feign to represent these women. Rather she “retrieves” and invokes them. Not true likenesses, Hinkle calls these works “unportraits,” because they are freed from the demand to represent an interior self or serve a greater good. Painting with her own improvised handmade brushes, Hinkle has managed, borrowing from Hortense Spillers in her essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” to strip down layers of attenuated meanings, made an excess in time, and find the marvels of black girls’ own inventiveness. The Evanesced is a monument to anti-antiblackness.

The figures in the series are ghosts Hinkle lives with, by whom she allows herself to be haunted, and who keep her company in her studio. They don’t so much “tell their stories” as come to dance, or to sit in stillness, to braid their hair, to masturbate, maybe to cry and fragment, to multiply and expand, to find pleasure or peace, or to be safe. In Hinkle’s rendering, joy and trauma live in the same place.

When I saw The Evanesced at the California African American Museum in LA in 2017, the one hundred 9 x 12 inch “unportraits” were displayed in a grid format, each carefully thumbtacked to a wall painted to match the paper. Affixed only at the top two corners, the pages billowed against the wall, the women almost floating in space. As a form of modernist visual arrangement, the grid generally has the effect of imposing order and structure, one that cancels the individual in favor of an abstract Universal. But here in The Evanesced the grid had a different effect: not order but excess. Each rectangle was not a coffin of containment but a window into whole worlds just beyond my purview. Reshifting my gaze in this way helped me look again at Begley’s 15,000 squares with softer eyes.

Yeshi Gusfield, “We need prominent and permanent memorials of every horror committed on this land. #niawilson,” September 4, 2018 (Instagram); image courtesy of the artist

Yeshi Gusfield, “We need prominent and permanent memorials of every horror committed on this land. #niawilson,” September 4, 2018 (Instagram); image courtesy of the artist