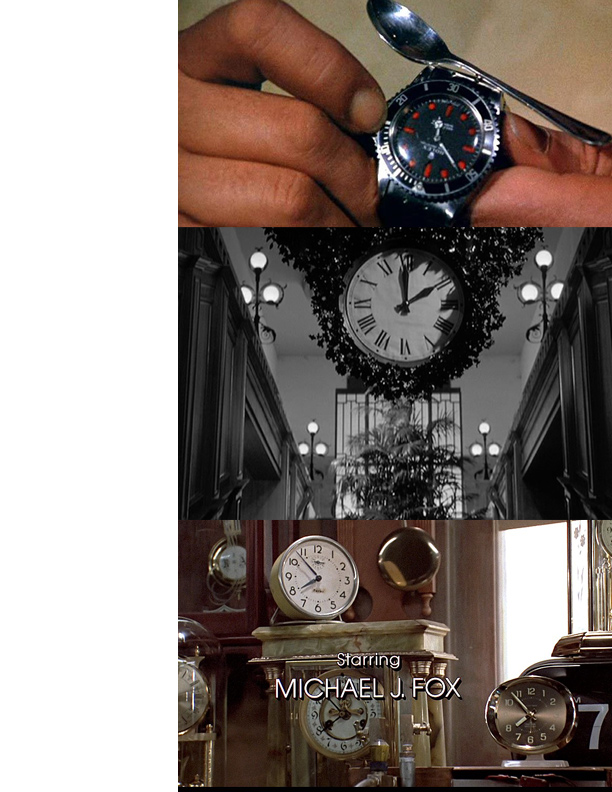

Notes on Christian Marclay’s The Clock, a 24-hour compilation of movie scenes dealing with the real time

First thought upon exiting the MoMa’s all-weekend, last-weekend showing of Christian Marclay’s The Clock, which we watched for nearly three hours, uninterrupted: What time is it?

It was, of course, the time last seen on screen plus 10 or 20 seconds, The Clock being set to EST, New York City. Was it my failure to integrate “virtual” and “real” that made me want to know what had been told to me every minute, on the minute, all evening? Was it merely reflex? Time is how we do things, one thing after another. We think of time-telling as a uniquely human ability, which is probably true, but it’s also true that as humans we are functions of time. We require something to do, somewhere to go, and so it is time, it must be time, what time is it? We can’t do another thing after one thing without stopping to know the time, and the time itself isn’t nearly as important as that we know it.

Or did I think to ask what time it was because I’d forgotten? Manhattan reminds you of the time constantly, Marclay does so continually. And because the time never went unchecked, The Clock let me forget it. That’s rare: We live amid a battery of screens; are seldom not monitored and/or self-monitoring; know the time almost to the minute, always. I only forget it when I write intensely and at length, have super-good sex or conversation, or get high as hell. The freest, the best times are like no time. The Clock, too, achieves a kind of temporal edge-of-seat free fall and one of art’s higher goals: transcendence of limits.

In this case there’s one limit that feels like the limit. It’s the limit that does not exist, is not time but the measure thereof, and those measures (the hours, the minutes) are limits we require in order to do things, one after another, and to believe that in doing we do freely. If there is no freedom without limits, there’s also no “free time” without the limits imposed by measuring time.

That measurement, from limit to leitmotif in The Clock, was the last thing on my mind as I watched it. I counted instead smiles, tears, bar drinks, blondes and redheads, Julianne Moore appearances, stormy exits, trains, automobiles, cold dinners, diamonds, escapes. How many moving parts make up the world. How much is always in motion at once. You couldn’t write a more linear film than The Clock, and it feels anything, everything but linear.

Marclay’s temporality (the supercut) moves contiguously at a quick, even pace from scene to scene, the way a movie does to show simultaneous action. But in a movie there are only three or four parallel storylines, and here, they are seemingly infinite. Sometimes we see more than one scene from one film, but that only reinforces the notion (or this cinematic technique as notion) of simultaneity, while the rest proves how incomprehensible that notion nearly is. The Clock feels like a highway, a freeway, with no speed limit and a zillion lanes.

All roads lead to midnight, but then midnight is just the minute before 12:01. For all the narrative elements achieved by clever sound editing and visual puns, if there’s no end, there’s no story. A million storylines don’t make one plot.

Marclay may have relied so heavily on old movies out of reverence, or because pre-digital stories have more clocks in them, but the effect is a fast-paced and slow dismantling of “history” as we know it. Without plot, the past is as destabilized and pixelly as the present. Most scenes feature strong action, many depict choices, but we never see the consequences and there is no denouement. Each scene seems to exist not by itself, but for itself, which is why this beautiful, scary-nihilistic thing seems such a momentous feat. It’s a macro .gif, or like Twitter: So much happens every minute. On the hour, nothing happens at all.

And at the end of the day, there’s no end.

I did think we would watch until midnight. We left around 9 p.m. All I wanted was a hot dinner and one long, very long, very still shot, like something from Wong Kar-wai or Sofia Coppola. Moments are times with no movement (no motion, no measure). Life happens in them, I think.

When nothing is happening. Everything else is just stories we tell ourselves in order to be functioning members of the moneymaking world.

This is the kind of thing I was left free to think about in The Clock.

And why when I left, free and hating it, I needed so badly to know the time.