Lying outside the state’s claims to sovereignty, the border zone both challenges and defines the legal conception of the state.

In the early 1970s, the city of New York started auctioning off public property to bolster funds against the growing economic recession. Among the pieces for sale were several strips of useless land, some measuring as little as a foot in width, created by zoning errors or orphaned by public works projects. The artist Gordon Matta-Clark bought 15 of these properties—almost all in Queens—with the intention of turning them into a project called Fake Estates. He visited his properties as best he could—many were in the middle of a block or locked between other lots—and measured and photographed them. He also amassed all the official records he could find on their “value” and how they came to exist. When Matta-Clark died in 1978, the properties reverted to the city for failure to pay property tax and his research went into storage. Although it was never completed, Matta-Clark’s project suggested a way to understand property ownership and value through tiny lots whose mere existence contradicted the prevailing logic that created them.

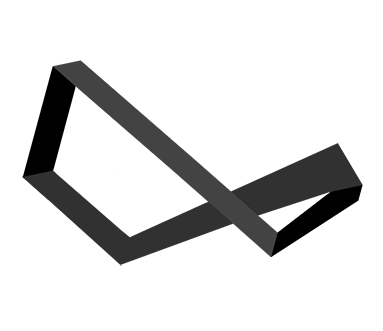

The spaces between national borders are like Matta-Clark’s slivers of property: their anomalous existence hint at the totality of the system that created them. Just as New York City allocates every piece of land for usable value, borders divide and embed territory with sets of law and sovereignty. In medieval times, borders were sprawling areas of dwindling or overlapping authority, far from sovereign seats of power. People could cross easily through different realms without passing any demarcation or checkpoints. The rise of the liberal state and advances in cartography solidified borders into exact lines, compressing that undefined border zone into a narrow and liminal space. If a sovereignty has always been defined by its territory, the rigid definition of borders is a fundamental (and foundational) aspect of the modern state. But even precise borders inevitably leave slight cracks between nations.

Sometimes these border spaces are a few miles wide, sometimes only a few inches, but they are widest where the generally precise and agreed upon national borders, usually thought of as a single line in space, are disputed or exist between hostile nations. On the Korean Peninsula, the demilitarized zone separates North and South, cutting a 2.5-mile-wide, 160-mile-long no-man’s land across the 38th parallel. Both sides of the zone are heavily guarded, and the empty space between is rigged with sensors, booby traps, and land mines. It is wholly devoid of people except for two “peace villages,” symbolically left in the space from which both governments withdrew since the 1953 armistice. Villagers in Daeseong-Dong, administered by South Korea, technically have South Korean citizenship, but they are exempt from taxes, military service, and other civic duties. The North Korean village Kijong-dong, meanwhile, is not even inhabited but is instead an elaborate concrete stage set, replete with automatic lights to make the buildings look inhabited and prosperous. Outside these two enclaves, flora and fauna have replaced human activity, transforming the DMZ into a strange nature preserve, an extremely biodiverse core sample cut through various ecosystems and supporting several species of endangered birds and a breed of endangered tiger. Natural vegetation has slowly erased all signs of cultivation and war.

On Cyprus, another armistice line runs across the middle of the island, creating pockets of extra-territoriality. In 1974, a coup which attempted to unite Cyprus to Greece triggered a brief civil war and an invasion by Turkey, who looked to support Turkish Cypriots in the North and maintain a Turkish sphere of influence. Fighting stopped under international pressure, but the armistice left the island partitioned into a Turkish Republic in the North and a Greek-Cypriot South by a United Nations buffer zone called the Green Line. Nicosia—the largest city on the island—is divided by the buffer zone. The U.N. built walls out of white and blue oil drums to seal off streets and alleys that connected one side of Nicosia with the other. As a result, several parts of the city were left in the space between, ostensibly administered by U.N. troops from the U.K. and Argentina, but actually they are empty zones, left to rot.

The Manifesta Foundation chose Nicosia as the location for its 2006 European contemporary art biennial and contracted Mai Abu ElDahab, Anton Vidokle, and Florian Waldvogel to curate. The trio conceived of an experimental art school that would traverse the various political and cultural divides of the island and challenge the prevailing standards of various European art events. Vidokle went a step further and planned to create his section of the art school in an abandoned hotel within the city’s buffer zone. When the plans went public, the local authorities balked, and Manifesta Six was canceled, triggering a series of lawsuits between the Manifesta Foundation, the local governments, and the curators. Cypriot artists accused Manifesta of using the border zone as a cultural fetish, while defenders argued that Cyprus’s inability to set aside bureaucratic protocols prevented an idealistic cultural exchange from taking place.

In the fall of 2011, protesters from both sides of the Green Line moved into the buffer zone and set up a tent encampment. The U.N. peacekeeping force issued several formal calls for the group to move out of the buffer zone but made no move to evict them. During the winter the occupiers took over several empty buildings that had been caught between the two borders and abandoned after partition. After several months, Cypriot antiterror police went into the buffer zone and brutally evicted the encampment, arresting people and sending those from Northern Cyprus back over the Green Line.

Manifesta 2006 and Occupy Buffer Zone were not the first attempts to engage with the extra territorial spaces within bisected cities. When East Germany erected the Berlin Wall, the exemplar cosmopolitan border, it made a slight deviation from the agreed-upon boundary, leaving a small portion of eastern territory on the western side of the wall. Separated from the East by the Berlin Wall and from the West by a simple chain link fence, weeds took over the lot, which came to be known as the Lenné Triangle.

In March 1988, the two Berlins reached an agreement to exchange various pieces of land orphaned on either side of the wall, including the triangle, which was to become part of a freeway in West Berlin. As soon as the agreement was announced, a group of West German squatters moved into the triangle and set up a barricaded encampment, declaring themselves outside the laws of either government. The West Berlin police, unable to enter the zone, asked the East German police to evict the squatters and push them back into the West, but they refused, citing the Wall as the limit of their jurisdiction. West Berlin then asked the Americans or Soviets to exercise their de facto authority as occupying powers and remove the encampment, but they also refused, perhaps out of fear of anything in the border zone that could put the two superpowers into direct confrontation.

Frustrated by the anomalous legal nature of the Triangle, the West Berlin police were reduced to playing loud music, shinning lights and throwing tear gas into the camp from their side of the border. The squatters for their part responded with stones and Molotov cocktails. As the stand-off continued, the camp grew to hundreds of people and even had its own pirate radio station. On July 1, 1988, the land exchange was finally formalized and the Lenné Triangle became part of West Berlin. The West German police moved in that morning and most of the squatters fled over the wall into the East, climbing homemade ladders and jumping into the arms of East German border guards who helped them down and gave them breakfast.

While the Lenné Triangle occupation is a nice anecdote of the radical potentiality of border zones, the eastern side of the Wall reveals more of their true nature. East German border guards might have welcomed West Berliners over the wall—no doubt eager to embarrass their municipal counterparts—but they mercilessly prevented East Germans from crossing to the West. The wall was built to prevent such defections and from its concrete height to a preliminary eastern border lay a 300-foot “death strip” in which all movement was forbidden. This strip also ran between East and West Germany from the Baltic Sea to Czechoslovakia. Border guards in overlapping towers were charged with preventing “violations of the border area” by any means, including shooting to kill. The area was covered with various booby traps and land mines, which, combined with shootings, killed several thousand people over the duration of the border’s existence. One of the most famous cases was Peter Fetcher, an 18-year-old East German construction worker who bolted across the dead strip for Check Point Charlie in West Berlin. He was shot in the side and fell tangled in the last yards of barbed wire, still alive but trapped in that nether region. Guards from both sides refused to enter the strip, and only after he bled to death did an East German official came to retrieve his body.

Borders are containers of law and so the exercise of laws, and by extension legal rights, stop at the border. But sovereign power—not to mention flows of capital and information—extend into and beyond the spaces between nations. Bodies caught in this nether region (or banished to it) are subject to state power absent legal protections. In its most extreme form—such as with Peter Fetcher—it is a place where the state can kill but a person has no right to live, a situation reminiscent of Agamben’s concept of bare life.

Recently, however, this interborder zone has been divorced from physical geography, becoming instead a condition transposed onto bodies rendered subjects of state power. In Steven Spielberg’s 2004 film The Terminal, Tom Hanks plays a person rendered stateless by a coup in his home country and stuck in the transit terminal at JFK airport, unable to either enter the United States or fly back to his home country. The story is loosely based on the story of Mehran Karimi Nasseri, an Iranian refugee who lost his passport in transit and was stuck in the transit terminal at Charles de Gaulle. Afraid to leave the terminal—and face deportation back to Iran—he stayed in the airport for 17 years. The courts in France ruled he could not be expelled from the terminal itself, as he had entered it legally, and he sat beside his luggage and lived on food airport workers brought him until he fell ill and was removed to a hospital.

In the very beginning of The Terminal, Hanks is actually cordoned off by ropes into a special zone, made temporarily and specifically for him. It is as if legal indeterminacy has been transferred from the in-between space of the transit terminal unto his person—a visual representation of the border zone’s projection beyond actual space. Across the industrial world, governments have set up immigrant detention centers, places designed to justify the extra-jurisdictional, extralegal status of those they detain. Immigrants and stateless persons held in those centers are rendered, as one researcher put it, “illiberal subjects still within the jurisdiction of liberal states.” The border can function then as a movable tool of state repression, extending deep within any national territory, producing the legal paradox of subjects within the territory of a state but excluded from the rights it supposedly guarantees.

In his book The Enemy of All, Daniel Heller-Roazen (a frequent translator of Agamben) examines this concept as applied to piracy. He traces the evolution of piracy away from a primarily territorial concern.

In the past, a piratical act presupposed, by definition, a specific area of the earth in which exceptional legal statutes applied. For centuries this region was that of the high seas. Subsequently, it began also to include portions of the air, once a legal theory of the earth’s most elevated zones had been developed. Today, however, this classic relation has been inverted. The pirate may no longer be defined by the region in which he moves. Instead, the region of piracy may be derived from the presence of the pirate.

Roazen goes on to show how the legal theory of the pirate has been transposed to the War on Terror. By situating the conflict “outside the borders” of any particular nation, the U.S. and its allies have pushed the war into a juridical space outside law itself. Those who fight in that space are neither criminals nor soldiers, afforded neither set of legal protections. They are instead unlawful combatants, like the pirate or medieval outlaw, banished from civil society and existing only as bare life between the borders of civilized nations.

Those who are captured instead of killed are removed to any number of U.S.-run extraterritorial sites. Guantánamo is the most well known and serves as the quintessential example of the indeterminate border zone as a place of absolute power. It is outside the legal jurisdiction of either Cuba or the United States but remains under the sovereign power of the U.S. military. As such, Guantánamo is a legal black hole in which the laws of the U.S. and the Geneva Convention do not apply. The unlawful combatants brought there from fields of operation across the globe can be held indefinitely, tortured, and even killed as a matter of administrative procedure. The extraterritorial nature of the camp threatens to be not the exception but the order of state power, especially U.S. military power.

Some might question the value of examining the nature of these scant extraterritorial spaces, given that bourgeois laws are always underwritten (and often overwritten) by other systems of power. But legality and governance operate according to their own almost self-generating logic, creating and manipulating categories of space. In Korea that space is a nature preserve, in Nicosia it is mirage of possibility, and in Guantánamo it is a horrifying detention camp. On one side of the Berlin Wall, the absence of legal jurisdiction protects squatters, while on the other it is cause for summary execution. These spaces are not uniform but share certain characteristics worth considering. If we have truly come to live in a sort of Kantian order of nation-states, fixed in geography and federated to one another as a world governance, then the existence of spaces not administered by that system—however small—seems significant to the order as a whole. Perhaps in the end they are the juridical exterior by which the interiority of states are made.