As it turns out, the Weather Channel has a regular audience of hardcore fans. And, among those people, the consensus is that something has gone terribly, terribly wrong.

As Sandy churned toward Atlantic City on Oct. 29, 2012, the Weather Channel was having a very good day. For a few hours in the early morning, TWC was the most-watched channel on cable: over 2 million people tuned in—more than CNN or Fox News—to track the whereabouts of the superstorm/frankenstorm/post-tropical nor’easter. The network, which is owned by NBC, took its good fortune in stride. In a press release the next day, TWC chairman and CEO David Kenny said, “People had an immediate need for information about Sandy. We were just happy they came to us for it.”

Weather events like Sandy might be the only times anyone has an “immediate need” for the Weather Channel these days, and even then, it’s a strong claim. Most people

Take former TWC fan PitLoad413 (his Yahoo username):

What has happened to the Weather Channel...my Weather Channel? Huh? Where the hell is it? Like an stereotypical 85-year-old man in his den, I would watch the forcasts and listen to the music for hours on end. Believe it or not I enjoyed seeing the temperatures change and ponder whether or not a snowstorm is coming our way...Now, we have our fellow Storm Trackers and Weather Geeks replaced by the snotty-voiced dumb broads with fake tits and metrosexual pretty boys with fake tans one would find on the otherwise less-sophisticated 24-hour news networks...Who thought that this would be a good idea to turn my Weather Channel into another dumb McNews channel?

PitLoad413 is apoplectic, and he’s not alone. TWC has become a “politically correct Anthropogenic Global Warming infotainment blizzard of chatty b.s. which has shouldered out the channel’s former comprehensive, useful, helpful hard weather data,” writes Jordynne L. And from Adam L., “I no longer watch TWC because they made all these annoying & aggravating changes. I wish it was like it was back in the early 80s.” And from an anonymous commenter: “I was 8 when I started watching, and I have tapes of the weather channel, and cry when I watch them.” What struck me first was the sense of personal betrayal in their tones. It spoke to a relationship much deeper than I thought was possible with a cable network whose most-watched program is called “Local on the 8s.”

TWC has had its share of devotees since it began broadcasting in 1982. These people are what I came to think of as The Base. They have favorite OCMs (on-camera meteorologists) from decades past. They recall major weather events like 1988’s Hurricane Gilbert and the east coast Superstorm of ’93. They share video clips from TWC’s “Major Meltdown” of ’08, which happened for one night Jan. 21-22 and involved a power surge, followed by the local forecast playing on continuous loop. With fondness, they recall the late-’90s commercials featuring a fictional bar called The Front—where face-painted diehards watched TWC as if it were football—and the slogan “Weather Fans, You’re Not Alone.”

Among them, there’s a sizeable subset devoted to geeking out over the tech specs of the various generations of WeatherStar/IntelliStar systems, which receive and process forecast and weather information. The only competing subset, in terms of forum-posting frequency and general vim, is of TWC music aficionados, who log and share virtually every song played on the channel.

Most of The Base agrees that TWC’s heyday was in the mid-to-late ’90s. 1995 seemed to be a particularly stellar year. Two live shows, “Weatherscope” and “Exposures” debuted. “I would know everything about the nation’s weather and the forecast in a nutshell after watching one segment of ‘Weatherscope,’” writes TWC fan-site administrator phw115wvwx, who purports to be a 30-year-old man from Blacksburg VA. “And the ‘Exposures’ series taught me so much about the weather yet only aired once a week for 30 minutes,” he adds.

Fans generally agree that TWC declined steadily through the early aughts until 2008, when it took a nosedive off a cliff. 2008 was the year Landmark, TWC’s original parent company, sold the channel to NBC for $3.5 billion. A number of beloved OCMs were canned, “Weatherscope” and “Exposures” were dropped, and the slogan was changed to the universally-derided “The Weather Has Never Looked Better.”

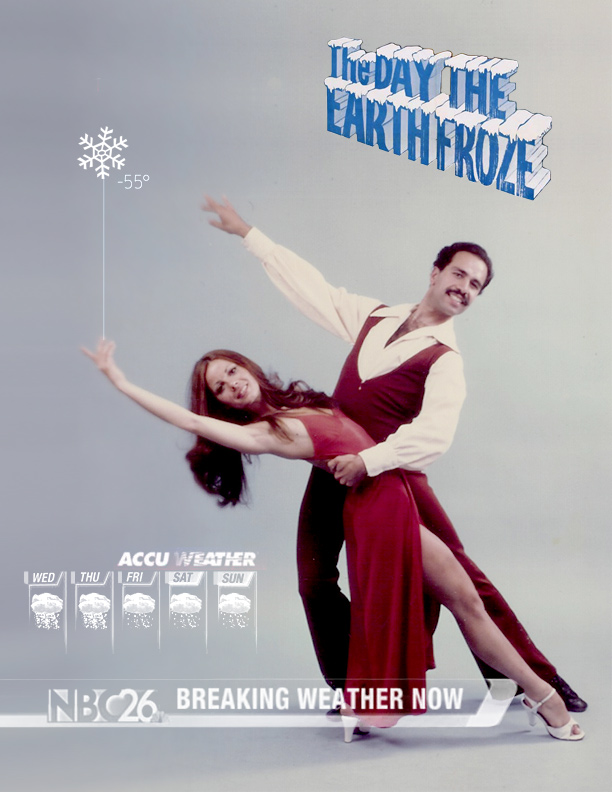

Then TWC started showing weather-related movies like “Deep Blue Sea,” which is about mutant sharks and stars Samuel L. Jackson and LL Cool J. “Misery,” a Stephen King adaptation in which there is a snowstorm, is another TWC favorite. During one such screening, TWC didn’t cut to live coverage of a tornado, and the uproar from both fans and casual viewers was deafening.

TWC abandoned the films in 2010 and has now been moving further into what it calls “original programming”—or, as the The Base would have it, “weather-tainment,” “the National Enquirer for Weather,” and even “weather propaganda.” There are about 20 shows on TWC now that probably fall into this category. They’re all reality shows about people doing dangerous things in bad weather situations—on icebergs, during hurricanes, tornadoes, etc.—or about weather doing bad things to innocent people. One show is called “Weather Caught on Camera” and is basically an assemblage of YouTube clips filled in with eyewitness interviews and expert analysis.

Some of TWC’s decisions have admittedly been in poor taste. But are such changes to a commercial channel’s programming really all that unforeseen? TWC is doing what every normal media-outlet does, i.e., it’s trying to entice viewers.

What I began to understand about The Base was that many of them are in denial about the Weather Channel being a commercial operation. They see it as a public service with a mission, and that mission, in their minds, has nothing to do with ratings. This perception is patently wrong, of course—this is, after all, cable television we’re talking about—but where does it come from?

The roots of our beliefs about weather forecasts—what they’re worth and who we trust to provide them—can be traced to magic, mysticism, and the supernatural. Predictions are essentially prophecies, and prophecies about the weather are as old as Genesis. Noah knew 100 years before the rains arrived, Moses gave a ten-plague forecast to Pharaoh, and Ezekiel predicted the kind of extreme weather the Weather Channel only wishes it could cover. Forecasting was an easier job back then; God did not beat around the bush. But it was also a sacred duty and a selfless act.

And perhaps it should be. The weather is perhaps the closest thing we have to a truly universal experience, not just because it’s the go-to subject for polite conversationalists worldwide. To risk sounding like a TWC promo, weather can be as powerful as an economic crisis and as deadly as disease or war. The only way to control it is to predict it, and we can’t even do that very well.

There’s also the question of quality. There are few professions in which being wrong is a daily if not hourly experience, but most weather forecasters are inaccurate the vast majority of the time. That’s because meteorology is a science based literally on chaos. The father of chaos theory was a meteorologist named Edward Lorenz whose breakthrough came while he was trying, unsuccessfully, to predict the weather with a computer model. He found that small variations in initial inputs (temperatures, wind speeds, barometric pressures) were leading to wildly divergent results. In other words, The Butterfly Effect.

So if weather forecasters are our modern-day prophets, they are also students of an imperfect science. In TWC’s case, they’re business-people too, and this creates all kinds of uncomfortable ethical problems. For instance, TWC has admitted that most commercial forecasters inflate the percentage-chance of rain because it’s better for business (people don’t notice if expected showers never come, but they get cranky if it rains when it isn’t “supposed to”). As Bruce Rose, former TWC VP, admitted in The New York Times, “If the forecast was objective, if it has zero bias in precipitation, we’d probably be in trouble.”

But TWC is already in trouble with its followers, and it has been for a while. The last straw for The Base came in early November when a Nor’easter trundled toward New York less than a week after Hurricane Sandy. TWC announced on its website that it would call the storm—and certain subsequent storms—by name, much like the system for naming hurricanes determined by a United Nations-affiliated group. TWC would call the first storm “Athena.” According to a press release, “a group of senior meteorologists” came up with an A-to-Z list of names, though it was more likely a crack legal team. R is for Rocky—“a single mountain in the Rockies,” Y is for Yogi—“people who do yoga,” and Q is for, uh, Q—“The Broadway express subway line in New York City.” Thousands of people reacted to the news on Facebook, TWC’s website, and other comment forums with varying levels of derision. “Name overload,” wrote one commenter. “These names for everything are way over the top,” wrote another. “Too big for your britches.” “Just cover the weather, don’t make up names for it.” “...a totally rogue action.” “I hope the NWS has the authority to force a stop to this disgusting behavior.”

The National Weather Service did, in fact, issue its own press release just hours later, forbidding its staff meteorologists from using the name in its “products,” i.e., its forecasts, warnings, alerts, etc.

TWC was unfazed. It cheerfully listed the reasons for its decision in a five-point plan that was actually a two-point plan with a few points rephrased, and concluded, “The question then begs to ask ‘Why aren’t winter storms named?’...It might even be fun and entertaining.” TWC’s indefatigable optimism is hardly surprising. After all, unflappability amid chaos is the channel’s modus operandi. Proverbial shit-storms sit squarely in its comfort zone.