To the extent that any prison sentence is also death sentence, O. J. Simpson may well be said to have returned from the dead. But any insistence on his death in the first place betrays the consensus view of reality, if only because Simpson is, by appearance and fact, not dead, no matter what Afropessimists might have to say about ontology’s antagonisms to blackness. And yet: It is right to observe that incarceration occasions a plunder of civil liberties in what, from the legislative perspective, is formally indistinguishable from the minimally capacitated status of the deceased; its ghoulish, transmuting power is to render (formerly) incarcerated subjects operative, if not always actual, corpses. We might term this occurrence social death, a process administered by that “peculiar apparatus” penality (to repurpose Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony”), and proceeding from our nation’s own peculiar institution. An extractive, disenfranchising establishment, the prison’s undispelled intent is a total denuding of subjecthood.

Such framing—tendentiously derived—would mark the prison as functional opposite of the commons, where repeated invocations of the self serve aspiringly to bolster and promote one’s subjectivity into life-affirming excess. This is useful logic for understanding Simpson’s late restoration. As if to assert his status (mythic, alive) he has turned to social media, that newest of commons, pursuant to a connatural, creaturely desire: instantiation of his ego, in the original Latinate sense of the word. O. J. has come to say I.

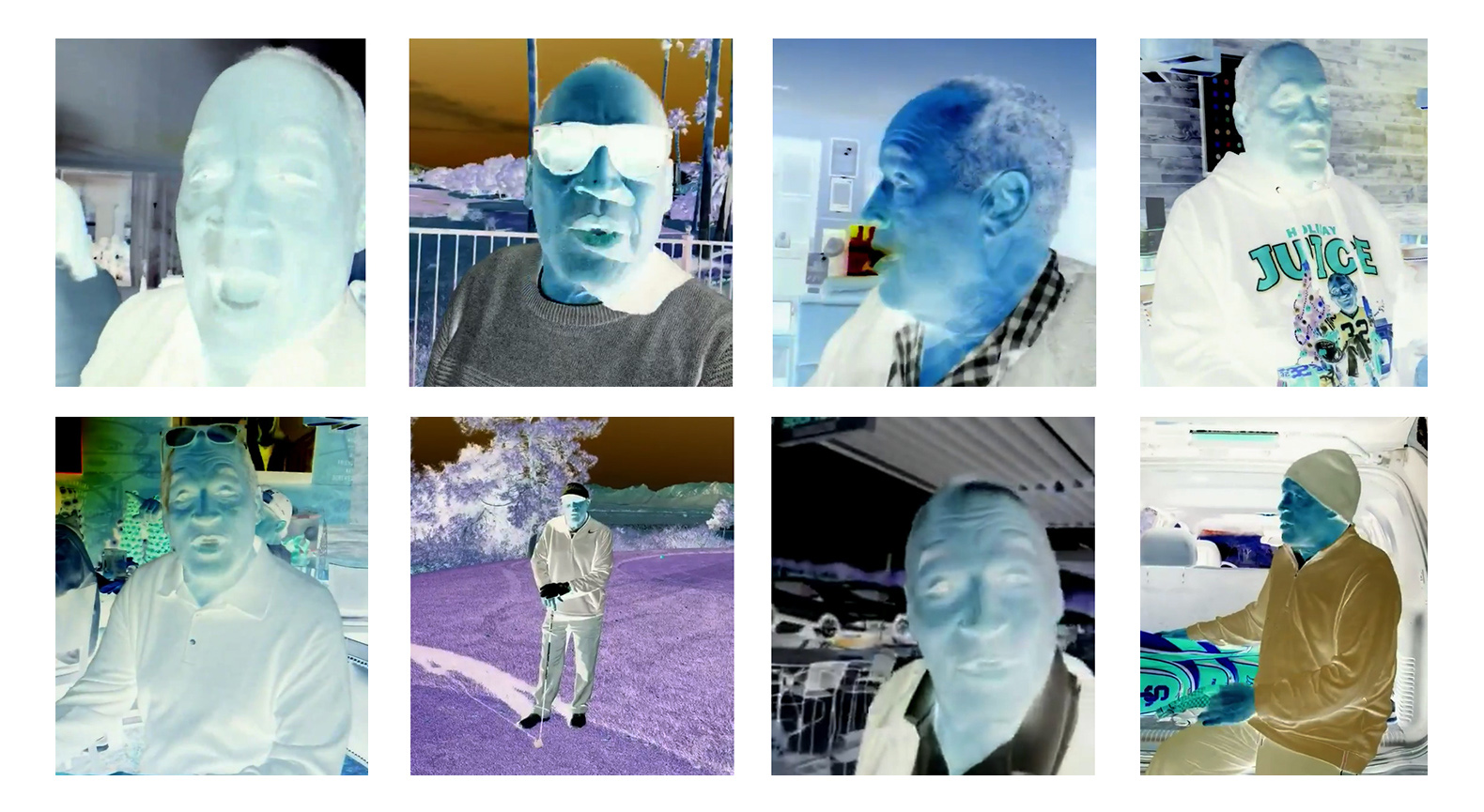

Simpson’s Twitter videos began to appear in summer of this year. The unforeseen first arrived as ambuscade—amid warming, precedentless June, a week before the solstice—unwelcome omen of an abstruse half year still to come. “Hey, Twitter-world!” the man hailed, in close-up. “This is yours truly.” As mode of address, it was classic, an epistle recalling through rewriting Shakespeare (“Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears . . .”). Yet it contained interesting violations of epistolary form, with the parting salutation (“yours truly”) used up top, and apparently to euphemizing, cozening, thoroughly ingratiating effect. What little else there was to note: Simpson spoke from the wide focal length of a cell phone’s front-facing camera; the act technically constituted vlogging. True to the vlog’s genre, he became more banal as he spoke: “Coming soon to Twitter you’ll get to read all my thoughts and opinions on just about anything . . . There’s a lot of fake O. J. accounts out there so this one, @TheRealOJ32, is the only official one . . . This should be a lot of fun. I’ve got a little getting even to do.”

I followed the unverified account, intrigued by the promise of a vengeance that I thought he had long ago exacted upon the world, and by the mystery of his “thoughts and opinions.” But I recalled the sophisticating, proliferating deepfakes, and was cautious. There was little need for trepidation. No parody or disinformation obtained. Here instead, evidently, was a cinema verité: dreary; nonscandalous; the work, in a sense, of a documentary auteur. Simpson’s thoughts and opinions were of sports and of athletes; his sense of revenge was historical, focused on amendment of an errant biographical record that he had felt to accrue around his name. In this he sounded like the cliché of a retiree father (“OK, boomer”), who offered ceremoniously the dim lights of his perceptions and recollections to an audience whose care extended from curiosity, or from a corrupted sense of cultural nostalgia. Still, I wanted to write about him, about his curiously wrought phenomenon, and to intellectualize through criticism his burgeoning oeuvre and Gesamtkunstwerk. I wrote a pitch, executing upon it no flattering revisions for the brief essay in which it would reappear:

What I’m interested in is the reappearance of O. J. Simpson, once a paragon of a certain kind of radicalized virility, as something we might recognize as daddish and Boomer-like, belonging to an aged fraternity of erectile dysfunctioning phallogocentrists. His mishandling of the medium of Twitter plays a hand in this re-envisaging. Here he posts videos—dispatches from his parolee’s purgatory—of himself engaged in what we might consider a region of re-enfranchisement studded, we know, with its delimited freedoms, and therefore recalling in that same nostalgic moment the surfeit of civil dispensations once enjoyed by the man. And incarceration has transmogrified his body, too: In the shaded sports lenses, brimmed hats, and relaxedly splayed collars of polo shirts, Simpson speaks to us from the slackening vessel of a Dad Bod, replete with its breasts and flabs—and approximating, in that way, a more “feminized” body. I want to consider this instance of convergence (of carceral conscription and en-gendering) as something fraught, and potentially revealing; that is, more than coincidental.

I’d like to say, too, that I want this piece to be rather un-self-serious, and maybe even ridiculous. Light of tone and humorous, if I can manage it. Yet I hope for it to retain some essence of rigor—analysis of a figure so emblematic of the kind of broadcast-delayed convulsions happening at the End of History, attributable to the unconscionable incursions of Western powers across the globe in earlier, midcentury decades. . . .

But I exhausted my interest in the same moment that I expressed it. The pitch and its essay became near-duplicate artifacts, the former contained in the latter, as in a kind of gnostic mise en abyme: self-returning replay of sentiment, ideation. The recursion seemed apposite, even convenient, as it corroborated the End as the End—locked and withheld in distinct, uninhabitable temporality unapproachable even by thought, indeed marking the final, impregnable terminus of so many converging vectors of world-historical machination.

This July 9th marked Simpson’s 72nd birthday, which he commemorated with another video. “I’m celebrating my 33rd annual 39th birthday,” he confesses from the end of a driving stroke of a golf ball. He feigns laughter at his own joke, which strikes as a recursion, too, an instance of semantic solipsism—return once more to the self—describing the limit of progressive speech, communication, interpersonal imbrication. A onetime culture-hero of a liberal democracy, his manner of relationality is unrecognizable, incommunicable. Perhaps Afropessimistically, his ontology finds a temporal/linguistic stymie, exists outside of the distension of event we call chronology. Simpson’s world, then, its histories and futures, ended three decades ago. He was his own arbiter, Horseman of the Apocalypse riding his white Bronco.