Some of the names in this piece are real (those of my grandparents, a well-known activist, and a celebrity). Others have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals who were involved but who may not want to be named.

Serge sat in a metal chair in a cramped office, trying to avoid staring at the KGB agent sitting across from him. He focused on his own shoes instead, chunky, ugly things, not quite the desirable Nikes he’d seen a young man wear the day before. The KGB agent narrowed his eyes and ran his tongue over his beige teeth, letting the hums of the air duct and the squeaks of the suspects’ chair fill the empty room.

“Your request for emigration has been denied,” the agent said. He turned the knob of a small television set resting on his desk and adjusted the screen so that both men would be able to see the image. “Do you know why you’ve been denied?” he asked as the TV tubes warmed up. Serge shook his head silently.

A middle-aged couple materialized on the screen. The woman carried a large bag and the man wore a tight tennis shirt tucked into casual slacks — clearly not from the USSR. “Do you recognize the two people in this video?” Serge shook his head, trying to look away. “Are you sure they don’t look familiar?” the man pressed. He spat his words out as if they had curdled in his mouth. “Their names are Murray and Helene Cohen, known Zionist spies,” he said. “You have been recorded associating with them.” He pointed to the TV screen, his finger tapping the glass with dull thunks. “tell me what you know about them and you might not go to prison.

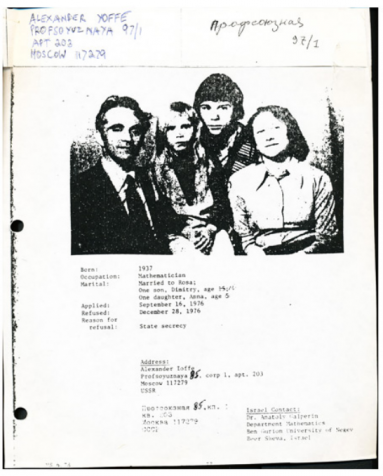

”My grandmother only heard this story years after it occurred. The man who’d attempted to emigrate was the brother of a refusenik she and my grandfather had met in the Soviet Union. More than 20 years later, they found themselves sharing a table with Serge at the bar mitzvah of some mutual friend’s grandchild. They’d had a file on him and everyone he knew, a binder of grainy xeroxes filled with the miniature life stories of more than a hundred families who’d been refused exit from the Soviet Union because they were Jewish, or dissidents, or both. Some had been sent to prison camps in Siberia; others were kept under constant surveillance, their homes bugged, their comings and goings recorded by a sprawling, state apparatus — a drab, yellow fog settling over their lives. These people were desperate to leave, but few were ever allowed. in June 1982, my grandparents, Murray and Helene Cohen, traveled to the Soviet Union as part of a secret mission headed by the Great Neck chapter of the long island Committee for Soviet Jewry in order to pass information and contraband goods to Jews attempting to leave Russia.

A few years ago, my grandmother moved with my late grandfather from their house in Great Neck, the home base for their Soviet operations, to the once swinging and now mostly walker-pushing North Shore towers. When I step into her apartment, my grandma immediately hands me a Greek yogurt, and with a spoon in my mouth, we sift through stacks of fat manilla envelopes filled with binders, photo-albums, and scraps of memorabilia from the trip/mission.

My grandma explains how she first heard one of her co-conspirators, who we’ll call Lisa Sanger, give a speech during a Shabbat service at her temple. The organization attracted her because when she and my grandpa joined, they were respectively the second and third members. “I didn’t want to be part of something where the secretary stood up and read the minutes from last week’s meeting and then everybody voted on this measure or that,” she explained. “If we decided we wanted to do something, I wanted to be able to do it, not spend all day debating it.” My grandmother neglects to mention some of her other personal reasons behind the trip. At the time, she and my mother were estranged because of my mother’s relationship with my father, whose appearance my grandma has described as similar to a “homeless Jesus.” At the same time, my uncle was just starting to come out of the closet, a process my grandfather refused to acknowledge, literally walking out of the room to run an errand when my uncle attempted the talk. Their nest was not merely empty, it was barren. While my grandmother would never connect her strained relationships with her children to her decision to go the Soviet Union, i think the situation of their cathexis is worth mentioning. Who better to replace your children with than the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union?

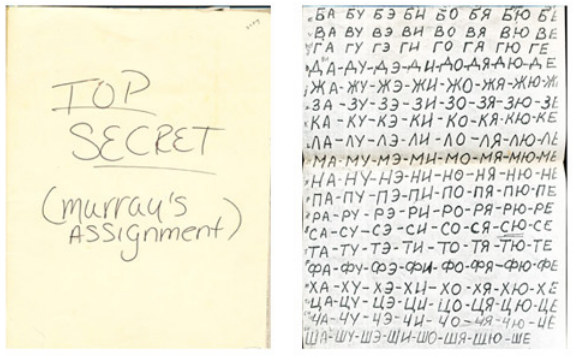

Their plan was relatively simple: my grandparents would go on a regular tour of the Soviet Union, stopping in seven cities across Russia and Ukraine. During the day, they would pretend to be just like everyone else, but at night they would secretly meet with people who their organization had already contacted in order to distribute the items they’d brought. In preparation, my grandparents attempted to learn a few key phrases in Russian, which my grandmother consistently referred to as “the cyrillic language” when I talked to her. However, this preparation turned out to be pretty basic, and for much of the trip, they relied upon Refusenik translators and the handful of sentences they’d memorized. They were not CIA material.

Unfamiliar Customs

We were requested to bring in quite a few things into the Soviet Union: one man wanted a shortwave radio, one man wanted a book by Henry Kissinger, another wanted a photography book. As people came out, they brought the requests of refuseniks who were still there, and we tried to follow through.

So when we arrived at customs to leave the U.S., we decided that your grandfather and I would go on different lines. My valise was packed so that it looked casual, but certain things were hidden if customs started to open it up. Well, I got through my line and I met our group at the other end. And Grandpa, they open his valise and the first thing they see is a big book by Kissinger and they didn’t understand, so they said, “Why do you have this book?” “I like to read,” he says. “And why do you have a shortwave radio?” “Because I want to hear the news from the United States.”

But the crème de resistance was when they opened photography book and saw pictures of nude women — that was it. So they kept him there, questioning him a good 10 or 15 minutes, while I was already on the other side. And my group leader said to me, “Who is that person?” and I said, “I have no idea.”

Moscow Mule

During the weeks to follow, my grandparents saw the sights and pretended to be an ordinary American couple on vacation, taking snapshots of Moscow out the window of their tour bus. To ingratiate themselves to their tour guides and hotel clerks, they used their Polaroid camera, a novelty many of the russians had never seen. its instant magic softened even the stoniest faces. They went to the markets, admired the views, and tried to eat the food like everyone else, but in the evening, they lived another life.

I had one of these Le Sac bags which expanded, and in that bag, I carried blue jeans, women’s pantyhose, and other things to sell on the black market. A pair of blue jeans could keep a family going, I think, for six months at that time. And so when we left the room, we took with us these bags — we actually looked like hobos.We didn’t talk in the rooms about anything that was particularly dangerous because all the rooms were bugged. In fact, there were light switches that didn’t turn on lights. We knew something was wrong. And we would not make any outside calls while we were in

the room.

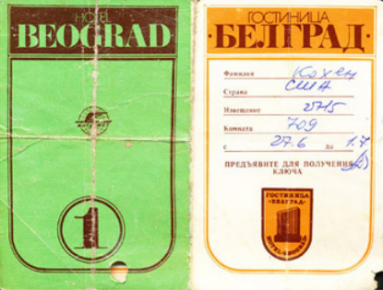

We had to leave our passports at the front desk, though we carried xeroxes we’d made in the U.S. and when we left the hotel, we would give the key lady our key . . . The key ladies were the most suspicious people of all because we never went out with the other people in the group in the evening. But because the bureaucracy was so awful in each area, nobody bothered to talk to police in the following area. We were incompetent, and so were they. When we got out of the room, we walked down two blocks or so, and we used a public telephone and called somebody and told them we were coming. I remember we used a dime, which was equivalent to the size of a kopeck.

To hail a cab, your grandfather held up either a pack of Camels or Philip Morris cigarettes because this was a very desirable thing to have. And all of a sudden, cabs zoomed in from all over, when you just held up something like that. We would write the addresses on little bits of paper — they were really less than the wrapping of a cigarette — and we would hide it in the hem of our clothes. We got in the cab and tore the paper in half and gave the driver the cyrillic instructions.

When we arrived at the address, your grandfather would sit in the cab, and I would go out to these buildings and I would have to ask somebody in the cyrillic language, “Where is so and so?” I only knew a few sentences. So that was part of our training, which was really inept; we bungled along like Peter Sellers, but we went. We also developed codes for everybody that we saw, and I developed so many codes that I forgot what the codes stood for.

Ida and the Orange

On one of our first nights, we were at Lev Blechshtein’s apartment with a lot of people, and we were giving away whatever we had in our knapsack. We gave pantyhose, tea, coffee — coffee was very difficult to get in those days. Even in the hotel, you only got one little demi-cup of coffee — no refills.

And while we were there, Ida Nudel arrived. She was really the vanguard for people who wanted to get out of the Soviet Union. She had hung up a banner on her window that read Let my people go! and because of that, she was sent to a Siberian prison camp for years. She slept with an ax under her pillow because there were wild dogs, thieves, rapists, and cut throats. But she knew that we were coming, so she managed to somehow arrange to get to Lev’s place.

At the beginning of the trip, my grandparents had a layover in Finland, where my grandmother had received a navel orange from the airline. She had stowed it in her knapsack for later and forgotten about it, only remembering it when she saw it nestled in a pile of women’s undergarments at Lev’s place. She fished the orange out and tossed it to Ida Nudel with little ceremony. Ida handled the orange gingerly, rolling it over in hands, smelling its skin, squeezing it in her palm. She cracked the seal around the bellybutton and the room filled with the fragrance of a fruit a long way from home. According to my grandmother, “She hadn’t seen an orange in years,” so they took a Polaroid of Ida Nudel using a knife to peel the orange, pith half-exposed and a childlike grin creeping across her normally stoic face. My grandparents framed an enlarged copy of the photo and kept it prominently positioned on their bookcase for years.

This was a regular tourist trip in the Soviet Union and we were told to try and make friends with somebody who didn’t know what we were doing. And we made friends with this couple who held up the tour one morning because they were arrested. The police thought they were trying to buy icons, which was very illegal.

When we were with Lev, we took the train to visit somebody, and the KGB was following us at that time. A man came up to us and asked us in the cyrillic language which soccer team we preferred because the World Cup was going on at that time. And Lev knew we were being interviewed and he said, “Leave them alone; they don’t like soccer.”

I know that when we went out early in the morning once, we were followed. We stopped at a store window and the person who was following — he was maybe 30 feet away — stopped at a store window and he looked in. It happened a few times, we would to look in a window, and then he’d have to stop, too. I said to your grandfather, “We’re being followed.”

White Nights

The last place we went to was Leningrad, which was never dark. It was light practically 23 hours a day. And your grandfather was very happy; he started to tear up all the papers of people we met and flush them down the toilet.

My grandmother says “very happy” here, but she means “experiencing his first major manic episode.” Throughout his adult life, my grandfather endured severe bouts of depression, describing its onset as a gray mist coming over his eyes. However, he’d never experienced what his doctors later diagnosed as a manic episode, and neither he nor my grandmother recognized what was happening to him in the USSR.

It helped him actually. He was absolutely fearless. He was the impetus that propelled us on because I was a little bit concerned. And he said “Don’t worry, and we’re going to go here, and we’re going to go there,” and he tore this [piece of paper] up . . . He had an enormous amount of energy. The only concern I did have was that sometimes, he was a very talkative. That was part of the illness.

My grandmother didn’t go into any detail, but my mother later recounted a story my grandparents told her when they returned. in leningrad, my grandfather had become particularly excited, talking loudly and animatedly, drawing stares and unwanted attention. Standing in a crowded elevator with my grandmother, my grandfather began to talk about their plans to meet someone later that night. My grandmother coughed and made all sorts of signs to indicate that he should shut up, but my grandfather wouldn’t be deterred. In a last ditch effort, my grandmother yelled over him, “Murray, are you thirsty? Do you want a drink?!” This phrase was supposed to be code for “Stop talking about secret spy stuff!” which must have seemed somewhat obvious to the many other people packed into the sweaty elevator compartment. Where would the drink my grandma offered come from?

Exodus

When we came back, the photographers were there, and I was very inexperienced and naive. And Lee [the president of the Long Island Committee on Soviet Jewry] whispered in my ear, “Your time will come,” and pushed me out of the way and let the photographers take her picture. So I learned a lot on my trip, and I learned a lot coming back, too.

The Guardian Angel

My grandmother and I wrap up our interview, chatting about the family and leafing through the stacks of materials she and my grandfather semiarchived after their trip. This is how I come across the tan folder labeled, “Murray’s Assignment” in which i find a xerox of an article clipped from a newspaper. The first line reads, “Soviet Jewish activist Ida Nudel celebrated her 53rd birthday last week in her isolated Moldavian cottage in southwest Russia — and actress Jane Fonda was the surprise guest of honor.” My grandmother remembers when the article came out in 1984. I continue to work my way through the documents: various copies and originals and of letters and articles on the Long Island Committee on Soviet Jewry, multiple versions of the report my grandparents wrote up detailing their adventures, and a letter my grandfather wrote to Fonda after reading about her advocacy for Ida Nudel. He opens with a few paragraphs about my grandparents’ time in the USSR and their own meeting with Nudel. Then in the third paragraph he writes, “Wild rumors were being circulated that you planned to make a movie, The Guardian Angel, the name given to ida by her fellow prisoners during her Siberian exile. Of course, we expected you to play the leading role, and that the film would gain world wide attention.” He ends the letter by mentioning that he’ll be in L.A. in a few weeks, and that he would like to meet somewhere and discuss their mutual interest in Soviet Jewry and potential film possibilities. No one ever made a movie with Jane Fonda as Ida Nudel, nor have my grandparents’ exploits been optioned for a future blockbuster, though my mother still encourages me to write the screenplay whenever a family member mentions the spies from Great Neck.