On their first arrival at the Tongva coast (what would now be considered the coast of Southern California), conquistador Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo and his men communicated that they had no intention of fighting, and so the Tongva people engaged in trade with the Spaniards. Cabrillo’s first visit opened the way for further expeditions to follow. Eventually, a few hundred years later, the Spanish decided to conquer the Tongva region and its people.

I’m sure there were some Tongva people who were resistant to engaging in trade with the Spaniards. Hierarchy probably silenced the voices that said, Don’t trust the strangers. If histories of colonization and imperialism teach us anything, it’s that one must always kill the scout.

In Los Angeles today you still see the friendly white scouts. They come into a neighborhood that hasn’t been taken yet, where the rent is still affordable, and there's a certain charm about the graffiti and trash on the ground that you don’t find in Silver Lake or Los Feliz. Here, they get the real LA. So they rent their own apartment, because they can afford it here, and they slowly start to walk around the community. They learn a few words of Spanish, shop at the local eateries, and become comfortable enough that they begin to invite their friends. A new apartment becomes available, because a family has just gotten evicted. They call their other white friend to move in, and they do, with no questions asked, because they’re white and that’s the only credit check you need.

Next thing you know, more of them bring their friends, and now they are using money their parents gave them from selling the house to open up their own business. Something that is easy for them, like a fancy ice-cream or coffee shop or, even better yet, a bar, because there are no bars for them and their friends to drink at, and they are the right shade to get a liquor license. So they do, one by one, then by the dozens, and the charming neighborhood that used to be filled with Brown people and fewer Black people (because since the ’80s Black people have been getting pushed out of Los Angeles due to targeted policing, the War on Drugs, and the 2008 housing crisis) is now white.

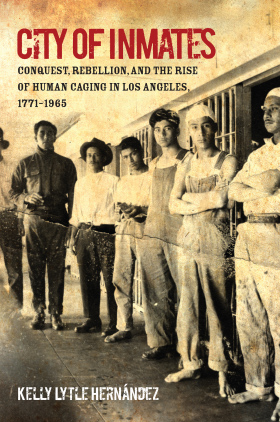

In Kelly Lytle Hernandez’s City of Inmates, we learn that the connection between these two scenes is prison. By examining conquest, colonization, and the use of imprisonment for population control, Hernandez details how successive authoritarian powers in present-day Los Angeles have targeted and captured people using cages to create what is now one of the world’s largest prison societies, and ends with a call for it to be destroyed. The Tongva people, “tramps,” Chinese immigrants, Mexican migrants, and Black people escaping the confines of slavery and Jim Crow all were and are the City of Inmates.

Hernandez opens the book by illustrating a time before there was a Los Angeles, before the first conquistadors had landed and the region was known as the Tongva Basin. Around fifty different villages lived and coexisted there before the Spanish colonizers began their “elimination” process. Hernandez uses the word elimination to denote activity “in the service of establishing, defending, and reproducing a settler society.”

Colonization has not ended. Gentrification is not its replacement but rather an added layer to the long trend of the dislocation of people by an authoritarian power structure. Hernandez’s argument that prisons are used to exterminate a certain population with the intention of gaining access to their land holds true today in Los Angeles. Gentrification is violent, it is cruel, it is meant to eliminate. If we want to protect our communities, if we want to have somewhere to live, then we must make white people feel uncomfortable.

I fantasize about driving down Sunset Boulevard with a carton of eggs, pegging each one of those eggs at all the white people dressed in their “this-is-what-I-think-someone-in-LA-dresses-like” costume. It truly is an enraging, grotesque sight. The epicenter for this is Silver Lake, which, after Forbes named it one of the “hippest cities” to live in in the U.S., went from an intermediate phase of gentrification to young yuppie overdrive in the span of five years. I see white people moving into the complex across the street and I feel afraid. I know that their presence will only lead to the further displacement of Black and Brown people and the continued colonization of those who are indigenous to what we now call Los Angeles.

As an anti-statist, autonomous, anti-authoritarian, horizontal deconstructionist, I believe living beings’ free migration is a crucial part of living freely and fully. This is the ideal, this is what should be; in reality, though, there are very few people on this planet who are free to move where they like. Race, sex, class, religion, and ability restrict where people live and travel. White people for many years now have been able to travel the world almost at will. They have been able to colonize land for centuries. And they can live in any community they can afford to, while a Black person of a high economic class will still face housing and banking discrimination, no matter how high their credit score and monthly income, because Black people are undesirable to landowners (this does, however, lead to Black middle- and upper-class people contributing to the displacement of other Black people in Black communities that have now been deemed desirable). If you are poor, living paycheck to paycheck, have a low credit score, and/or have a felony, good luck trying to find a place to rent in Los Angeles.

Gentrification and settler colonialism are layered, but linked by their methods of controlling land and people through prisons. As a Black person who lives in an anti-Black capitalist society and whose ancestors were slaves, I will never call myself a settler or a gentrifier. For there is no place in this world where I, a Black person from America, truly belong. We belong everywhere and nowhere all at the same time. This doesn’t mean that the shortage of affordable housing doesn’t cause me to participate, or even loosely benefit from, the displacement of other people. The capitalist scarcity of housing has enabled an environment where displaced people must aid in the cycle of displacement.

This is why protecting our communities is a matter of life and death. There are very few communities left for poor Black and/or undocumented people. These neighborhoods that are trendy to white people are the only places that don’t do credit checks, that will rent to nonwhite trans and queer people, convicted felons, or people who do not have documentation. When we talk about Los Angeles being a sanctuary city, it is not because of the mayor or the LAPD; it is because these communities have been able to build a stronghold over their neighborhoods and provide resources to each other.

If you are a white person who claims to be radical, you should not be moving into Black and Brown communities. White people overall need to give up their inheritance and wealth and distribute it to indigenous and Black people while allowing room for reparations to refugees from other colonized/war-torn nations. White people who are alive now should pay not only for the crimes of their ancestors but for the continuing structural benefit of white supremacy and the existing American empire.

Hernandez closes her book with interviews from members of various nonprofits and established community organizations working in Los Angeles today. In a chapter on the Black experience, she gives space to more organic forms of rebellion, particularly the Watts Riots, a Black-led uprising that terrified the white community. On August 11, 1965, a police officer arrested Marquette Frye, a young Black man, in the Black belt of Los Angeles. South Central, a part of the city that was used to harassment and violence committed by the police, had reached its boiling point. Onlookers joined Marquette’s family, who had come to try and retrieve his car to avoid it being towed, swelling to a crowd of at least a thousand. After Marquette and his family began scuffling with officers at the scene, the crowd began to riot; they destroyed property and looted stores, their rage spreading across Watts like wildfire. The event spurred white flight, which led to many white families leaving parts of Los Angeles for the suburbs, where they could better implement sundown laws and housing restrictions.

This moment of organic resistance set the conditions for the mechanism of modern-day urban development and the uprooting of Black people in Los Angeles today. When white people left, the urban cores were left to Black people. But their white descendants would find new value in the economic conditions that their grandparents created. And with restored interest, “city boosters” would revive the dream of the “Aryan city in the sun,” with an increased role for cages.

What Hernandez lays out so eloquently in her book is that in order for colonization to be “successful,” the detainment and caging of human beings is required. Hernandez condenses 194 years of incarceration into six chapters, each showing the same pattern. In the first chapter, we see that both the Spanish and Mexican settlers created jails as a means to rid the land they intended on conquering of the Tongva people. It is here that we are introduced to caging as a method of population control.

This is a continued theme: There is always a need for more jails and prisons, because there is always a population that is undesired and needs to be controlled.

While liberals denounce Trump’s Muslim ban as un-American, Hernandez’s narrative shows how controlling the migration of nonwhite people into the United States is consistent with the country’s history. The genesis of America’s current deportation laws was in containing the expanding Chinese immigrant population. The anti-Chinese lawmakers in the United States used a vague loophole in already-existing laws to justify the detention of an individual without having to find them guilty of committing a crime. “Detention is a usual feature in every case of arrest on a criminal charge, even when an innocent person is wrongfully accused, but it is not imprisonment in a legal sense,” the United States Supreme Court concluded in their decision in favor of the use of detention centers for immigrants undergoing deportation procedures. This loose definition of detention is what the state uses to this day to justify detention without proven “criminality.” The United States government's determination to restrict migrants led to further discriminatory laws directed at banning “all prostitutes, convicts, anarchists, epileptics, ‘lunatics,’ ‘idiots,’ contract laborers, and those ‘liable to become public charges’.” As well as “polygamists, criminals, and all Asians” who were already included at the time of the Act.

Authoritarian societies restrict people's autonomy by detaining and jailing them with the intention of removing and eradicating them from the land. In the case of California, vagrancy charges created an easy way for the city to control and remove Tongva people from public landscape of the city. Hernandez highlights this strategy when discussing the ramifications of such invasive anti-native policies. “By shifting large portions of the local Indian community from the streets of the city to the county jail, largely on public order charges, imprisonment operated as a system of removing Natives from the life of the city.” She explains how public order charges were used to purposely displace native people: “Local elites mostly used the county jail to cage substantive portions of the Native community. . . . Establishing the rule of law in Anglo-American Los Angeles, therefore, mostly meant denying Natives the ‘right to be’ in Los Angeles.” But colonizers found that they did not have enough space to forcibly hold all of those who were being arrested, so vagrancy charges allowed for the Tongva people to be auctioned off into slavery.

There was resistance by the Tongva people to the imprisonment, of course: jailbreaks were a common occurrence. Hernandez details one story where, in March 1853, native people who were incarcerated took advantage of a stormy night and the adobe walls of the jails and carved a hole they used to escape. With each wave of targeted prisoners, overcrowding became a larger problem for the city—something that persists to this day, as the city continues building more jails, prisons, and detainment centers. It is a grim kind of construction growth, based on laws where we forcibly cage people for breaking laws that were created for them to break.

Learning the history of how incarceration grew in Los Angeles reveals the indisputable fact that incarceration is still being used as a tactic to eradicate Black and Brown people from LA. This continuity between then and now is apparent throughout City of Inmates. We see how, by creating laws that criminalize and punish ways that people exist publicly in society, the state gives itself ample opportunity to make targeted arrests. And as in the early 1900s, houseless people especially are still terrorized for not having a place of residence.

The unity among the earliest stages of Spanish, Mexican, and then Anglo-American colonization was their exertion of zero-sum autonomy over those with darker skin. While the “tramps” may have been white, they too threatened the heteropatriarchal white supremacist structure, according to Hernandez. Even if they continued to receive some of the structural benefits of whiteness, their houselessness, joblessness, and often nonheterosexual status disrupted other whites’ fantasies about building a puritanical society in Los Angeles. Although Hernandez gives a chapter to white targeted arrest in Los Angeles, which had a role in overall increasing jails and prison labor in LA, the period in which the city was focused on caging the “hobo” population was still limited when compared to the long-term incarceration of Black and Brown people.

How does an authoritarian power control an autonomous individual? By force. Animating layers of colonization, white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, and capitalism is an underlying fear of autonomous people. These settlers did not want to coexist with the people of the region if they could not control them; they wanted to claim the land as their own through expropriation and domination. Autonomous communities in LA, such as the ones in Skid Row and those under the freeways near Silver Lake, consistently face harassment from the police and other fascist residents. The images of people sleeping, urinating, and drinking near million-dollar structures destroy the fantasy of control that the city boosters sold and the gentrifiers bought. So they continue to destroy their homes, throw away their tents and belongings, all in the name of “public health” and “public interest.” But who gets to be the public? Who gets to decide? Spring Street in Downtown LA, just a few blocks away, is filled with bars and people walking down the streets publicly intoxicated. Drink on Skid Row, though, and an LAPD officer can and will arrest or even kill you.

When the video surfaced of a longtime Skid Row community member, Africa, being shot and murdered by the police, it was not the first time or the last time that the city was involved in the death of a member of the Skid Row community. Like the genocide of the Tongva people, elimination is not just a matter of direct murder but also one of neglect and incarceration. It is not hyperbolic to say that there is a genocide currently happening in Los Angeles, to the houseless population. Whether it’s through lack of shelters, lack of access to health resources, being shot or beaten by a police officer, or deadly weather conditions, it seems the city’s only plan to address “homelessness” is to either arrest or kill people, directly or indirectly.

The legacy of imprisonment as a method of eradication that Hernandez writes about in City of Inmates continues in Los Angeles today. The city plans to build a new jail that will focus on “psychiatric treatment” and have up to 3,885 beds. Without direct actions to hamper the complete construction of the facility, Consolidated Correctional Treatment Facility will be built. This “facility” is not too far from Skid Row, an area that both the city and Central City Association are eager to develop for further gentrification. If we continue with the analysis that jails are created to cage people intended for displacement, it is not too far of a reach to see who is intended to fill those beds.

Although there are nonprofits and organizations in Los Angeles that are focused on “abolishing” prisons and jails, their methods are still highly focused on reform and pleading to power. Hernandez discusses how members of the Black middle class created a Los Angeles chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in order to form a community accountability initiative addressing the continuous harassment and killing of Black people by the LAPD (sound familiar?). That did nothing then, as the use of these same tactics continues to do nothing now. If we want to stop incarceration, displacement, and the overall violence that is inflicted on nonwhite people in Los Angeles, it will take direct action. It will require more wildfires like the ones we saw in 1965 and 1992.