You must always be yourself no matter what the price. It is the highest form of morality. — Candy Darling

The specter of the “superstar,” that shining icon who transfixes our collective gaze, looms large over contemporary culture. On television, RuPaul’s catty Drag Race reality competition recently crowned “America’s next drag superstar” at the end of its third season. Advertisements for American Idol, one of the most watched television shows in American history, affirm, “Every superstar begins with a dream,” and frame the show as the pathway to that dream’s fulfillment. Even the Country Music Television network airs a Next Superstar competition show.

If reality television has become a means to “superstardom,” the idiom has been further democratized by the would-be queens of the pop firmament, meshing personal liberation with the allure of iconic status. Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” describes the radiance of stardom as an innate quality found within each person, declaring that “we are all born superstars.” Ke$ha’s “We R Who We R” similarly claims, “You know we’re superstars,” while Katy Perry’s hit “Firework” rallies her equally luminescent listeners: “Even brighter than the moon, moon, moon.”

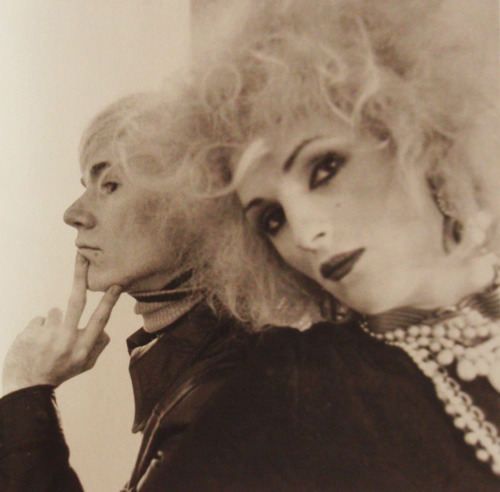

The original tribe of self-proclaimed Superstars, however, was Andy Warhol’s Factory crew of “odds-and-ends misfits, somehow misfitting together,” as the artist described them in his memoir, Popism. Within this tribe, the Warhol Superstar that most extravagantly combined silver screen Hollywood glamour with downtown New York chic was Candy Darling, the transsexual actress who worked alongside drag stars like Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis. A performer at peace with the costs of her identity, Candy’s career and lifelong scramble for stardom ended prematurely when she died of leukemia at the age of 29.

A documentary about her life and career, Beautiful Darling: The Life and Times of Candy Darling, Andy Warhol Superstar, began its theatrical run April 22 at the IFC Center in Greenwich Village. The film, written and directed by James Rasin, was produced and spearheaded by Candy’s best friend, Jeremiah Newton. Lauded in early reviews, the inspiring and tragic documentary is composed of clips of Candy’s performances and interviews with contemporaries like Fran Lebowitz, Julie Newmar, and John Waters. Throughout the film Chloe Sevigny reads wistful excerpts of Candy’s diary.

Beautiful Darling celebrates one of Candy’s most quoted statements: “You must always be yourself no matter what the price. It is the highest form of morality.” This declaration still resonates in a time of right-wing picketers, school bullying and gay bashing. If Candy was thoroughly disillusioned by dreams that went unfulfilled, her quiet resilience solidifies her image as an enduring Superstar. As Candy writes in her diary, “I am a star because I have always felt so alienated and I project this feeling to others.” By so honestly sharing her pain and her peace, the Beautiful Darling story strikes a chord with those pulled to the flashing lights that so captivated the Warhol crew.

The cinematic power of Candy’s image was also visible in Wynn Chamberlain’s 1969 subversive classic Brand X, recently screened for the first time in forty years at the New Museum. In one of the comedic skits that make up the film, Candy assumes the role of “Marlene D-Train” and romps around with Sally Kirkland and Warhol Superstar Taylor Mead during a game show titled What’s My Sex. Candy’s coy character is of course a playful nod to that paragon of silver screen sensuality, Marlene Dietrich, who was no stranger to gender-bending film scenes. In an email message, Chamberlain recalled that he “thought Candy would be perfect for a cameo and she was very good and easy to work with.”

Beautiful Darling director Rasin also attended the New Museum screening. When asked about surprises he encountered while making his film, he replied:

“One thing I always noticed about everyone I interviewed about [Candy]: they all said that she was the most genuine person that they had ever known. And I thought, ‘How could someone who is all about artifice be someone who is so highly respected as being so genuine?’ Candy was originally someone I was very skeptical of, who then became someone I came to greatly admire and respect, not only as a human being but as an artist. I guess that was the biggest revelation: this is an artist. Someone who has achieved genuineness, ‘truth’, through total self conscious artificiality.”

Today, one of the most visible inheritors of Candy’s aura is Darian Darling, the lifestyle blogger and nightlife personality who hosted the Beautiful Darling release party at Don Hill’s. Reviewing one of the weekly parties hosted by the “beauteous blonde,” Gerry Visco of the New York Press described her assembly as “a mix of the glam rock crowd, queers and hard-core punk club kids.” At the Beautiful Darling party, Darian read from Candy’s diary and was followed by pounding rock odes to Candy and the Warhol era by Michael T and others.

That night, Candy’s contemporaries mingled with fans and scholars developing new research on Pop’s heyday. Feminist art historian Kalliopi Minioudaki chatted with playwright Robert Heide, who developed the scenario for Warhol’s film Lupe. Thomas Kiedrowski discussed his forthcoming Andy Warhol’s New York City with Agosto Machado, who vividly describes his drag performances with Candy in the film. Rasin shared a booth with George Abagnalo, another interviewee in Beautiful Darling and co-writer of the screenplay for Andy Warhol’s Bad.

In explaining the Darling half of her stage name, Darian’s blog describes her Superstar namesake as “ethereally beautiful even without taking hormones or having plastic surgery. She was a pioneer.” This nod to a bygone New York moment was proposed by Darian’s close friend and collaborator, Lady Starlight. In a 2010 photo series shot by Veronica iBarra, Darian partly reenacts Candy’s photo shoot scene from Paul Morrissey’s Women in Revolt. The scene features Candy, robed in a shimmering black dress, striking a seemingly endless series of dramatic poses. This sequence, a perfect instance of what Amy Taubin described as Candy’s “melodramatic diva image,” is adapted by Darian, whose photos accompany her recipe for “Candied Darling Cookies.”

By uniting her fondness for baking fine confections with the sparkle of a Warhol Superstar, Darian mixes a dash of domesticity into her own bid for superstardom. She is not alone in pushing a distinctive brand of theatricality that perpetuates Candy’s performative enterprise. If Warhol filled his Factory with outré identities like Ondine, Ingrid Superstar, Ultra Violet, and Viva, Darian’s fellow downtown denizens include the likes of Breedlove, Miss Guy, Tommy Hottpants, and Kayvon Zand.

Although the country has changed dramatically since Candy’s death in 1974, the allure of Manhattan’s new wave of “filthy glamour” and the dreams of star struck American youth have only been amplified by the anxieties of our hypermodern age. Judging by the drawings and paintings recently produced in homage to Candy, Beautiful Darling resonates with so many because of its portrayal of an artist whose exterior yielded its own truth. The melancholy that runs through the film only highlights Candy’s faith in her own authenticity and the pride in acknowledging that she was, well, born that way. In this sense, the film finds common cause with shows like Drag Race and Glee and the rallying messages of today’s pop stars. Whether found in the up-and-coming idols of broadcast television or the revelry of New York nightlife, superstar dreams renew the urge to find a realm where the worth of one’s own identity can be celebrated, critics be damned. In disenchanting times, a refusal to be diminished by the world’s scorn, a lesson taught poignantly by the peace of Candy, can be a forceful display of power.