As more aspects of our lives are digitized, literature is an increasingly crucial means of expressing, understanding, and preserving places and their influences.

At the end of the eighties, when I was in middle school, a development threatened a parcel of land a half-mile down the road from my house in Whitefield, Maine. The town held a public forum for residents to air their concerns, and my parents took me along. Our neighbor Edmund Blaney was also at the meeting, held in the windowless basement of the town hall. The Blaneys owned a generations-old commercial apple orchard, and, as we were the only girls our age around for miles, their daughter Maggie was my frequent playmate. In most matters, the Blaneys and my parents, who were not from Maine but had moved there from California in the seventies, held opposing views, but about the development they were of one mind. They were against it.

As I remember it, my parents objected on environmental and preservationist grounds. Edmund argued that the increased traffic the development would bring would cause more accidents at the already dangerous intersection at the end of our road. The noise and pollution, he said, would also negatively impact our stretch of road, where both Edmund and his wife had grown up and where their parents and siblings still lived. Though my parents and I were smack in the middle of Blaney-land, the character of our road mattered deeply to all of us, and I remember feeling relieved that the development had as strong an opponent as Edmund. People would pay attention to him because he was from there. He was also a big man with a deep voice.

Perhaps it was then, in this moment of unity, that I realized the importance of what the Blaneys and my family had in common: a strong sense of the place we lived in. Not only did we know this place, we belonged to it. Our stretch of road had emotional weight. Yi Fu Tuan, the founder of the field of human geography, writes in his seminal 1977 book Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience that any given space is transformed into place through a “concretion of value.” This value is conferred through experience, beginning with the senses. Sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch are the primary means of understanding our surroundings: the shape and color of objects, how sound carries in the distances between them, whether the air smells like rotted food or like pine trees. “Sense of place” is the sensory evocation of meaningful space. The sensory character of Hunts Meadow Road was important to us, and we did not want it to be degraded.

As a writer and editor, sense of place is an aspect of literature I have come to value and seek out, not only for its power to reveal character, shape narrative, and distill mood and language, but also for spiritual sustenance. Perhaps the most eloquent and true sense of place I have found in contemporary fiction is in Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping . Nearly any sentence plucked from the novel will serve as an excellent example, but consider these, in which the narrator, Ruth, is awakened in the pre-dawn by her aunt Sylvie:

When Sylvie put the light on, [the room] still seemed sullen and full of sleep. There were cries of birds, sharp and rudimentary, that stung like sparks or hail. And even in the house I could smell how raw the wind was. That sort of wind brought out a musk in the fir trees and spread the cold breath of the lake everywhere. There was nothing out there—no smell of wood smoke or oatmeal—to hint at human comfort, and when I went outside I would be miserable.

Robinson delivers a stirring sensory experience that simultaneously tells us what the place—both the room and the surrounding town of Fingerbone—means to Ruth. The room cannot protect her from the painful cries of birds nor the musky smell and cold breath of the glacial lake. This is the kind of place in which outside and inside boundaries are permeable, exposing its people to the elements.

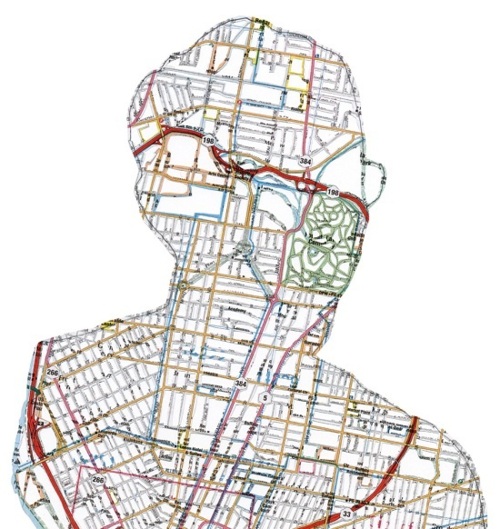

Perhaps more important than illustrating how Fingerbone matters to Ruth is Robinson’s assertion that it does . Place, the intersection of geography and culture, has always been paramount in human life, but the rise of digital technologies—the world wide web in particular—has both shrunk our interaction with real places and dimmed our awareness of their fundamental importance. The benefits of the internet are undeniable. It nonetheless presents, in its current form, a shallow means of intellectual and emotional engagement. This shallowness is a result of its vastness, its speed, the plethora of simultaneous options it provides, and most importantly, its lack of physicality—the denial of full sensory experience.

In his keen and delightful book on the search for authenticity in modern life, The Thing Itself, Richard Todd discusses tourism’s impoverishment of the individual, which I think also holds true of traveling the web. The activity of sightseeing can wear one down because of the distance created between the observer and the observed. As much as we seek “unimplication” in the world we are touring, he says, the experience leaves us feeling empty and anonymous, part of a “declassed, identity-blurred worldwide mob.” We seek novelty but are dissatisfied by the limited way the new experiences impact us. He writes, “Though we wear our travels, when they are over, like badges, while we are actually traveling we suffer constant little erosions of self-regard everywhere we go.”

This blurry, distanced, vaguely self-loathing experience is recognizable to anyone who has surfed the Internet. Studies, such as those cited in Nicholas Carr’s 2008 article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?,” have found that we do not truly engage in online content, preferring to “power browse.” We scan the headlines for information or search for items of temporary entertainment value. Our minds are working to become more like search engines, repositories of facts and images that are neither connected by argument nor weighed down by sentiment. Though there is plenty of potential interest to see and listen to online, the absence of our other three senses and the closely related sensory activity of movement prevents digital experiences from engaging us and becoming meaningful in the way that physical places and real-world interactions can and do.

As Robinson’s Housekeeping demonstrates, literature (printed on paper and devoid of hyperlinks) is an art form uniquely suited to maintaining our sense of place, this tremendous source of meaning in our lives. Well-crafted stories and essays provide the benefit of tourism (novelty of experience, understanding how other people live) with what sightseeing lacks: sustained engagement and reflection. As more aspects of our lives are digitized, literature is an increasingly crucial means of expressing, understanding, and preserving places and their influences.

The housing development on Hunts Meadow Road never did go in. That five-acre plot is still a wooded parcel of land with a half-started, overgrown driveway. A superfluous length of chain blocks the entrance. My parents and the Blaneys are still neighbors. Immutability, however, is not the point. The point is that as long as we have physical bodies, the physical world and its sensory qualities are going to matter to us, and any attempt to deny them for too long or too fully is bound to be an unhappy one.