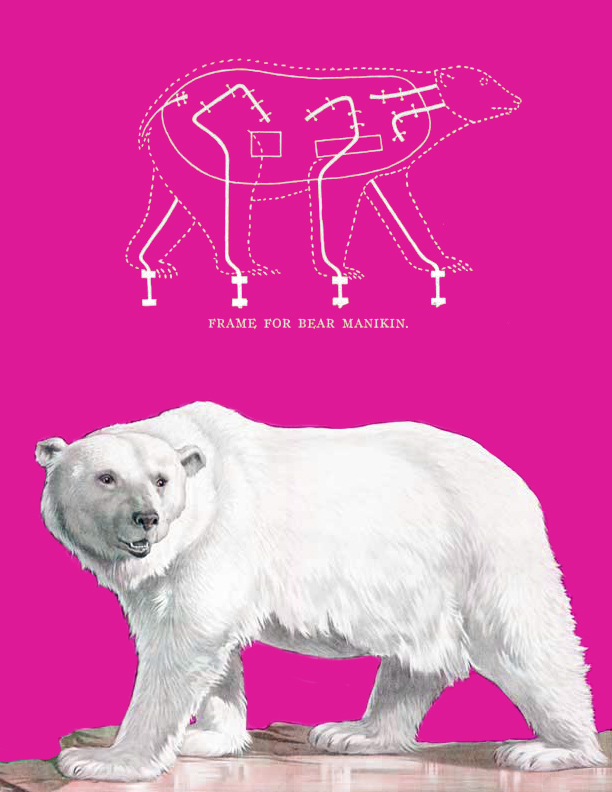

In 2004, the exhibition Nanoq: Flat Out and Bluesome opened in Spike Island, a large, white-walled art space in Bristol, England. On display were ten taxidermied polar bears, each isolated in its own custom glass case, all transported from separate locations

This is an except from The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and The Cultures of Longing now available from Penn State U Press

This is an except from The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and The Cultures of Longing now available from Penn State U PressEach of the bears was photographed in situ where Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson discovered them, captured in the mix and muddle of their dwellings, not their native environment, to be sure, but their second and more permanent home. Although the photographs exude a colorful vitality, there is also an indeterminate wistfulness to the images, a sense of lingering or waiting: the gentle sadness of the bears’ stoic persistence in the face of artificial ice floes, bottles of beer, and African animals. One of the bears holds a wicker basket of glowing plastic flowers; another is penned in between a wallaby and a tiger; yet another has been forgotten behind a dust-covered bicycle and a child’s rocking horse. The compromising situations envelop the bears in a vague sense of noble tragedy, an aura captured by the project’s ambiguously melancholic title: Nanoq: Flat Out and Bluesome, “nanoq” being the Inuit name for polar bear. “Flat out” implies death, fast forward, and flatten like stretched skins, while “bluesome” suggests both the bluish light of Arctic snow and the weight of melancholia.

The wistfulness of the photographs and exhibition title was sharpened by the display of the ten bears themselves. The atmosphere of the gallery was marked by a sense of absence, an uneasy silence, a loneliness and longing. Perhaps it was the austerity of the space, with its white walls, white floor, glass, clean white metal, and isolated honey-white bears. Or perhaps the sheer physical presence of the bears captured and communicated something that two-dimensional photographic images never could.

As part of their project, the artists researched the personal history of each specimen. The bears were variously shot during Arctic adventures or euthanized in zoos. One died of old age; another traveled with a circus. But whatever their precise story and route, polar bears are aliens to Great Britain; they were all taken from their native landscapes at some stage of life or death and manhandled into everlasting postures. The artists’ choice to document specimens of an Arctic species, rather than creatures indigenous to Britain, adds a layer of significance to the polar bears. These are not “common” indigenous creatures. They are not unwanted invasive species but coveted imports, and as such arenecessarily endowed with longing. Without the desire to capture, to kill, to see, to document, these bears would not be in Britain and certainly would not have been taxidermied.

Many of the bears date to the mid-nineteenth century and linger as relics of Victorians’ fascination with the Arctic. The bear at the Natural History Museum in London may have been killed during Captain Parry’s efforts to find the Northwest Passage in the early 1820s. The National Museum of Ireland’s bear was shot in 1851 in Baffin Bay during a reconnaissance mission to discover the fate of the Franklin expedition. The bear in the Kendal Museum was shot by the earl of Lonsdale on an Arctic voyage prompted by the request of Queen Victoria, and the bear in the Dover Museum was one of sixty shot during the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition, which unexpectedly encountered Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen and Hjalmar Johansen from the Fram, who had survived overwinter on polar bear and walrus meat. And with this early history, the bears also evince the Victorian infatuation with taxidermy itself. Some of the bears were preserved by the greats of late Victorian taxidermy, most notably Rowland Ward and Edward Gerrard & Sons. The bears’ aggressive standing poses make clear the era’s reveries of exotic animal dangers in distant lands. As such, the bears are documents of a British cultural imaginary which has slipped—thankfully or not—forever into history.

More pressingly, from a contemporary perspective, the bears can also be read as an anxious narrative of global warming. Here are so many bears from territories under threat. But if the bears are troubling environmental documents, they also stand as quiet educators. They offer visitors an opportunity to experience the majestic size of polar bears and to appreciate personally, intimately, the dignity and exceptionality of the species. If the bears provide a critique of past collecting practices, they also make material the intrinsic worth of preserving animals. If a creature becomes extinct, no matter how much video footage and photographic images may have been amassed, nothing can ever compare to the physical presence of the animal, admittedly dead and stuffed, but a physical presence nonetheless. The taxidermied remains of passenger pigeons, quaggas, great auks, and all other extinct species are precious beyond words. They are the definition of irreplaceable.

On display in Spike Island, the bears are also purloined objects of science. The majority were taken from natural history museums where they stood as examples of their species and representatives of Arctic whiteness. The display of ten polar bears is most probably a unique historical occurrence. It would be rare to see ten polar bears—a typically solitary species—together in the wild, and such an assembly would never occur in a natural history museum. Most museums have a solitary bear, having neither the space nor the educational need to display more than one. More than one is unnecessary repetition. Amassed together within the neutral space of an art gallery, disconnected from the didactic trappings of a natural history museum, the polar bears are transfigured by their multitude and setting, together becoming animal-things that are neither fully science nor fully art: mysterious, unsettling, provocative, and overwhelmingly visually magnetic.

A one-day conference held in the gallery, titled “White Out,” engaged speakers to discuss the bears’ significance. The title suggests a blizzard, an environmental obliteration, a toxic erasure of words and meaning, a blank slate, a new beginning, always with the bears as off-white canvases on which humans have inscribed meaning. The ambiguous title is fitting: the physical presence of the bears cannot be entirely explained with language. Even living bears present a complex of interpretations. “We have witnessed how in living human memory,” Snæbjörnsdóttir and Wilson write in the exhibition catalogue, “the image of the polar bear has been appropriated and put to the most varied and unlikely purposes—selling dreams, sweets, lifestyles, travel.” A formidable predator and a Coca-Cola icon of kitschy winter wonderland fantasies, the polar bear is “a catalogue of paradoxes,” a “prism with the capacity to contain and refract all manner of responses in us: fear, horror, respect, pathos, affection, humour.” How much more complex are taxidermied polar bears? From one angle, the polar bears are trophies of nineteenth-century British infatuation with Arctic territories; from another, they are cautionary tales offering traces of human activity carved in nature. They are contemporary art, scientific specimens, natural wonders, and symbols of contemporary environmental anxiety. They offer the opportunity to observe intimately a fearsome man-eater and indulge in the sheer pleasure of looking at beasts that may be nearly two centuries old. At once symbolic and individual, both victimized and saved, the polar bears resist any easy interpretation. And it is this ambiguity that makes them such potent objects.

As dead and mounted animals, the bears are thoroughly cultural objects; yet as pieces of nature, the bears are thoroughly beyond culture. Animal or object? Animal and object? This is the irresolvable tension that defines all taxidermy. What, then, do the ten bears communicate to viewers? What, for that matter, can any piece of taxidermy offer? Do they talk about their makers, about human romances and obsessions with animals and nature? Or do they tell us something about themselves? With taxidermy there are no easy answers.

The reasons for preserving animals are as diverse as the fauna put on view: to flaunt a hunter’s skill or virility, to contain nature, to immortalize a cherished pet, to collect an archive of the world, to commemorate an experience, to document an endangered species, to furnish evidence, to preserve knowledge, to decorate a wall, to amuse, to educate, to fascinate, to unsettle, to horrify, and even to deceive. This list can be simplified into eight distinct styles or genres of taxidermy: hunting trophies, natural history specimens, wonders of nature (albino, two-headed, etc.), extinct species, preserved pets, fraudulent creatures, anthropomorphic taxidermy (toads on swings), and animal parts used in fashion and household décor. A sportsman’s trophy is a very different object from Martha, who was displayed alongside other extinct birds at the Smithsonian Institution: the last American passenger pigeon, a species shot to extinction by nineteenth-century hunters. And both are different again from Misfits, a disconcerting series of taxidermied animals by the internationally acclaimed contemporary artist Thomas Grünfeld, which includes such composite creatures as a monkey with a parrot head and a kangaroo with ostrich legs and a peacock head. Different again is a stuffed pet, or a herd of caribou posed in a “natural” scene behind museum glass, or a miniature diorama of kittens having tea. Despite the diverse causes for taxidermy and the plethora of genres, and however counterintuitive it might seem, I argue that all taxidermy is deeply marked by human longing. Far more than just death and destruction, taxidermy always exposes the desires and daydreams surrounding human relationships with and within the natural world.

All organic matter follows a trajectory from life to death, decomposition, and ultimate material disappearance. The fact that we are born and inevitably disappear defines us, organically speaking. Taxidermy exists because of life’s inevitable trudge toward dissolution. Taxidermy wants to stop time. To keep life. To cherish what is no longer as if it were immortally whole. The desire to hold something back from this inevitable course and to savor its form in perpetuum exhibits a peculiar sort of desire. Why this piece and not another? Why the yearning to detain what should have passed from view? Taxidermy is hardly a simple or swift practice. It takes patience, skill, time, and labor, all of which depend on an intense desire to keep particular creatures from disappearing. No doubt there are many idiosyncratic motives, but in my book The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing I offer seven incentives—what I call narratives of longing—that impel the creation of taxidermy: wonder, beauty, spectacle, order, narrative, allegory, and remembrance. The seven longings take different shapes. Some are aesthetic hungers; others are driven by intellectual concerns, memory, or the force of personality, but they share a similar instability. Yet, to a degree, all seven longings are palpable in all taxidermy. All taxidermy is a disorientating, unknowable thing. All taxidermy is driven to capture animal beauty. It is always a spectacle, whose meaning depends in part on the particularity of the animal being displayed. It is motivated by the desire to tell ourselves stories about who we are and about our journey within the larger social and natural world. It is driven by what lies beneath the animal form, by the metaphors and allegories we use to make our world make sense. And finally, taxidermy is always a gesture of remembrance: the beast is no more. As the very word longing suggests, fulfillment is always just beyond reach.

Longing is itself a peculiar condition. It works as a kind of ache connecting the stories we tell ourselves and the objects we use as storytellers. In a sense, longing is a mechanism for both pacifying and cultivating various lusts and hungers by creating objects capable of generating significance. And here, objects of remembrance or souvenirs are exemplary.

A souvenir is a token of authenticity from a lived experience that lingers only in memory: a plastic Eiffel Tower from a trip to France, a shell from a beach walk, a ribbon from a wedding bouquet. It is the longing to look back and inward into our past, to recount the same stories again and again, to speak wistfully, that gives birth to the souvenir: without the demands of nostalgia, we would have no need for such objects of remembrance. But nostalgia cannot be sustained without loss, and souvenirs are always only fragments of increasingly distant experiences or events, and so are necessarily incomplete, partial, and impoverished. Yet this loss is precisely a souvenir’s power: never fully recouping an event as it actually was but resonating with golden memories. In other words, a souvenir is a potent fragment that erases the distinction between what actually was and what we dream or desire it to have been; equally important, its existence depends on the impossibility of fulfillment. The longings and daydreams encapsulated by souvenirs can never be fulfilled—the cherished experiences exist forever in the past.

Remembrance is only one motivation for taxidermy, yet it offers a solid illustration of the relationships between storytelling, potent objects, and the uncertainty (or impossibility) of complete satisfaction that underlie all taxidermy. Taxidermy is motivated by the desire to preserve particular creatures, but what motivates that desire is something far more nebulous than the animal on display: the coveted object both is and is not the driving impulse. As with objects of remembrance, all narratives of longing and their taxidermied animals work together in curious circular tension. On the one hand, desire creates its objects: taxidermied animals are not naturally occurring. On the other, it is the animal itself that activates, substantiates, and perpetuates human craving for its vitality and form. This unfulfillable desiring permeates all taxidermy: the longing for the beast (for its beauty, menace, or familiarity) scars the beast’s beauty, menace, or familiarity.

The seven longings take their own shape and emphasis, but they are all driven to capture and make meaningful the potency of nature. If we were unaffected by nature, we would have no need to render it immortal. It is this simultaneous need to capture pieces of nature and to tell stories—whether cultural, intellectual, emotional, or aesthetic—about their significance within human lives that marks taxidermy so deeply with longing. We do not desire souvenirs from unmemorable events, and the same is true of all pieces of preserved nature: we do not need or desire parts that cannot speak to us of where we are, what we think we know, and who we dream ourselves to be.

Storytelling is an important component of all encounters with taxidermy and, for that matter, most encounters with nature. By storytelling, I mean human interpretation and the creation of significance: the way we pull pieces of the world into meaningful and eloquent shapes. From cave paintings of animal spirits to zoos, from pets to hunting trophies, nature and all its nonhuman inhabitants have remained vital to the human search for significance and fulfillment. As Stephen Kellert writes, the “human need for nature is linked not just to the material exploitation of the environment but also to the influence of the natural world on our emotional, cognitive, aesthetic, and even spiritual development. Even the tendency to avoid, reject, and, at times, destroy elements of the natural world can be viewed as an extension of an innate need to relate deeply and intimately with the vast spectrum of life about us.” The parts of nature we fear or admire, the ways we connect with animals, the philosophies we project over the natural world, and the hierarchies we build are all forms of human striving to make sense of our world and our place within it. Yet nature is its own abundance and exists beyond “meaning,” which is forever a human urge and imposition. More often than not, what we choose to say about nature reveals more about human beliefs, desires, and fears than it does about the natural world. This is not to say that nature is forever trapped beneath a murky human-painted veneer and always best appreciated as a construction of cultural and political agendas. But it is to say that nature is a chaos of forms and colors and shapes and forces, and the various ways in which that chaos has been untangled and made legible should never be taken as nature’s truth but rather as nature’s possibility within a human imaginary.

Taxidermy is one medium for imposing the possibility of meaning or, more accurately, for exposing the human longing to discover meaning in nature, but always obliquely and often in contradictory ways. There is nothing unequivocal about the practice except that the animals are dead but not gone. Derived from the Greek words for order, taxis, and skin, derma, taxidermy literally means the arrangement of skin, but the practice has never been a pragmatic process of assembly. How could it be? It requires the death of our closest compatriots—our fellow sentient creatures. But while death is what makes taxidermy possible, taxidermy is not motivated by brutality. It does not aim to destroy nature but to preserve it, as if immortally, and to perpetuate the wonderment of nature’s most beautiful forms. As such, taxidermy always tells us stories about particular cultural moments, about the spectacles of nature that we desire to see, about our assumptions of superiority, our yearning for hidden truths, and the loneliness and longing that haunt our strange existence of being both within and apart from the animal kingdom.