Russia Today, the politsiya, and Western punks alike all want to know: Who is Pussy Riot, when is their next gig, and where can I get their album? Despite having no releases or merchandise for sale, no tour dates, no Myspace, or even recorded music, the band of masked women who only perform aggressive guerilla shows has achieved a level of punk legitimacy not reached since the era when the combination of bleached hair and three chords was on its own automatically scandalous.

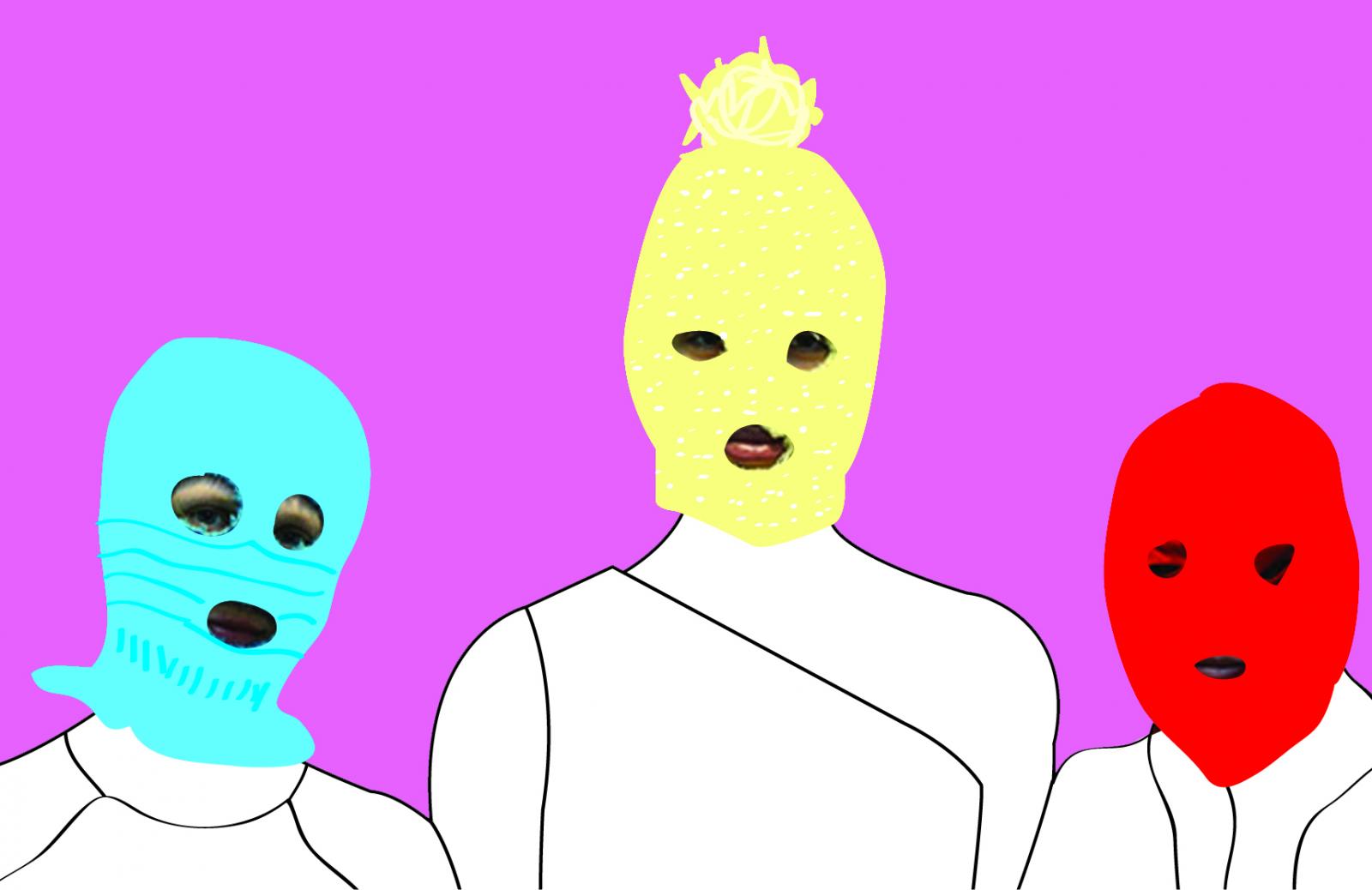

The days of the Fraternal Order of Police suing the Crucifucks, Tipper Gore taking on the Dead Kennedys, and black metal goblins burning churches are long past. Punk is now no more a social threat than some leftist fringe group selling poorly designed newspapers. And yet, with three of its alleged members now imprisoned and facing seven-year jail sentences, the pastel-balaclava-wearing, sloppy-guitar-playing riot grrrls have become an icon of a brewing cultural revolution in Russia.

Pussy Riot's now famous performance of Punk Prayer in Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow’s Kremlin, which earned them the personal ire of both the Orthodox Church’s patriarchate and Vladimir Putin himself, was a call for the Virgin Mary to become a feminist and exorcise Putin. Other feminist and anti-authoritarian performances included disrupting a fashion show by taking over a catwalk, performing unpermitted in a posh boutique, and playing a song called “Freedom to Protest — Death to Prisons” on the roof of a building in a Moscow prison complex to jailed anti-Putin protesters.

Last week a “Party Riot Bus” circled Moscow blasting punk rock and stopping for news conferences and performances calling for the release of the imprisoned band members. Riot grrrl matriarch Kathleen Hannah released a video pledging her support to the band, telling her fans she would “see you out in the streets.” A concert in Tallinn, Estonia to support the band drew several notable politicians, including President Toomas Hendrik Ilves.

On the flip-side, counterprotesters have attacked supporters in Moscow, focusing on removing the masks of female supporters. An anti-Pussy Riot rally was held the same day is Krasnodar, drawing an estimated 10,000 calling for a “moral revival” in the “fatherland.”

The band has derived their success — and scorn — by turning contemporary punk culture on its head. Where punk was once relegated to musky basements, squats, and other shabby makeshift venues, Pussy Riot makes all public spaces — the streets, the metro, the church — their stage. While punk bands play for punks, Pussy Riot plays for commuters, police, and clergy. While punk bands seek fame with glamorous pseudonyms and outlandish rockstar antics, Pussy Riot is masked. While punk bands engage in nihilistic lyricism, Pussy Riot’s songs are direct attacks on the confines of their authoritarian state and patriarchy. Since punk fell from the pop charts in the early 80s, it has been sent on a quest to define and sustain its own identity, creating punk houses, venues, record stores, and community centers, resulting in the introverted and self-obsessed situation of the sub-genre today. Pussy Riot does precisely the opposite.

It is fitting, then, that one conservative Russian website translated Pussy Riot to “Uprising of the Uterus.” What was once scandalized, forbidden, subaltern, rises from its rightful caste hidden and below and speaks in the very locations of its oppressing power. Who are these women, these punks, to perform, to pray, to protest in sacred locales? To desecrate is one of punk’s existential tasks. The smashing of sacred relics conjures society’s most archaic reactions: in this case, imprisonment, public shaming, flogging, concerns of Satanism, witchcraft, hysteria.

Punk has needed a Pussy Riot for so long. In many ways, it is the literal projection of the riot grrrl movement, which employed satire and third-wave theatrics to intervene in the traditionally macho and misogynist punk scene. It succeeded in creating a new type of punk — the grrl — but, until now, it had never successfully caused a riot.

Through the 2000s, bands have unsuccessfully attempted to wreck cultural terror. There was San Diego’s the Locust, who wore masks and bodysuits similar to Pussy Riot, played noisy and aggressive punk, but were not actually anonymous, nor were their lyrics directly political. The band shocked a lot of punks and sold a lot of records, but had very little cultural impact outside of their genre. Black metal-heads became enamored with the “Cultural Terrorist Manifesto” which also has had seemingly no effect. In 30 years, punk had perfected only gestures.

Perhaps part of the reason punk has begun to lash out so effectively in the former Soviet Union is the nature of the extreme oppression in Russian society. I spoke to Moscow anti-fascist Kostya about the dual dangers to the Russian anarchopunk — the right wing and the State:

I came up with the scene when it was possible to organize a strictly antifascist show, and you could be sure that only the right people will visit it. But still there was a danger of being attacked by Nazis before or after the show. Today it continues, but the situation is even worse. First of all, nobody fights with the fists, you’re more likely to be stabbed or shot with a traumatic gun. Secondly, and what is worse, there is strong oppression from the state and police. The situation in Russia isn’t stable, that’s why the government tries to control all the young people who can be dangerous today or in the future. They always try to put the same number of Nazis and anarchists in prison.

Kostya tells me Russia has its own anti-activist police force, called the “Department of Fighting Extremism.” Along with the threat of right-wingers burning down political squats or punk venues, the result has been a neutralized public face for the punk scene. All radical politics have been forced underground. It is no surprise, then, to see it return masked.

In 1977 the Ramones toured America like an Armed Struggle cadre of cultural terrorists, all dressed alike, playing the simplest and loudest music yet formulated. They not only invented punk that year, but they planted it everywhere they went. Punk’s success was its virility; reproducing with such ease that soon there were Ramones at every corner of the globe.

Reacting to increasingly technical progressive rock, the Ramones liberated the guitar to the world. Pussy Riot has taken this communization a step farther. To be a "member" of Pussy Riot, you don’t need to be able to play guitar or even to know the original band. As one member, Garadzha, told the newspaper Moskvkie Novosti: “In principle anyone can join.” You don’t even need to sing very well, she continues. “It’s punk, you just scream a lot.”

What would be the shape of punk outside the confines of the world of rock music? If Pussy Riot is any indication, it appears at scenes of intense banality or oppression. They have appeared on the catwalk, on top of a prison, and of course at the altar. They sound something in between a streetpunk band (Blatz’s Fuk Shit Up is the first thing to come to mind) and an battle-worn activist giving an impassioned speech through a megaphone. The precarity of their performances gives a new spin to the typical speedy bursts of punk — the songs need to be so short because they could be apprehended any second.

Everything about the band is similarly practical. The rawness of their sound reflects the semi-improvised site-specific nature of the songs. Their masks obscure their identities from police detection. Their bombastic performance (use of fire, flares, and the iconic punch-dancing) makes up for the lack of amplification. While other novel punk bands form their own stylized front against the limits of society, society’s limits seems to have fully formed Pussy Riot.

Perhaps antagonistic counterculture, once self-ghettoized within the margins of society, is beginning to coalesce into a new political form, one that transcends both its anti-social roots and the populism that activism too often demands. The Occupy movement is the most obvious example, but disruptive feminist and queer situations similar to those created by Pussy Riot have occurred in the United States over the last several years. The radical queer group Bash Back! disrupted service at a Lansing, Michigan Megachurch, making out on the pulpit and dropping pro-queer flyers. Repetitive comments by law enforcement official that rape is a result of women’s attire lead to massive anti-rape and sex-positive “Slut Walk” protests last year. With a new right-wing offensive against women escalating to the withholding of contraception and forced trans-vaginal ultrasounds, the coalition between the Church and authoritarianism is as relevant in the United States as in Russia. Could time be ripe, then, for some of the aforementioned agitators to arrange a Pussy Riot U.S. tour?