Abrahamian explains why a salon revival may be the best way to fight epistemic closure in the digital age— where the internet is a medium that never forgives, and never forgets.

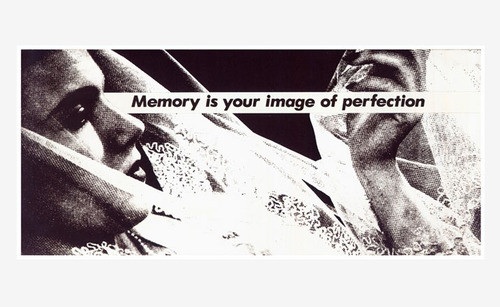

Before the digital age, we took for granted that a social faux-pas, a bad night out, a simple mistake would be eventually forgotten; in fact, our youth was wagered on the premise that awful haircuts and embarrassing behavior in our formative years wouldn’t be held against us later on. Forgetting allowed us to fully experience the lexicon of adolescence: we grew out of the tantrums and into our noses; we grew tired of the circus and fond of the theater; in short, we were given the freedom to grow up and not look back.

Today, we air our dirty laundry in real-time; we haven’t even a moment to reflect before it becomes a part of our virtual D.N.A. In The New York Times Magazine’s July 19 cover story, “The End of Forgetting,” Jeffrey Rosen laments the Internet’s capacity to systematically archive personal identity, arguing that the threat of lifelong searchability makes it increasingly difficult to reinvent ourselves and that our society is experiencing a “collective identity crisis” as a result. He invokes a familiar cast of characters in the narrative of online privacy: the schoolteacher fired for her Facebooked drunkenness; the teenager laid off after admitting she was “so totally bored!!!,” the Canadian senior citizen who once dabbled in hallucinogenic drugs and now cannot cross the U.S. border. These stories were once quite shocking; today we hardly bat an eye and blame the subjects for their lack of savvy.

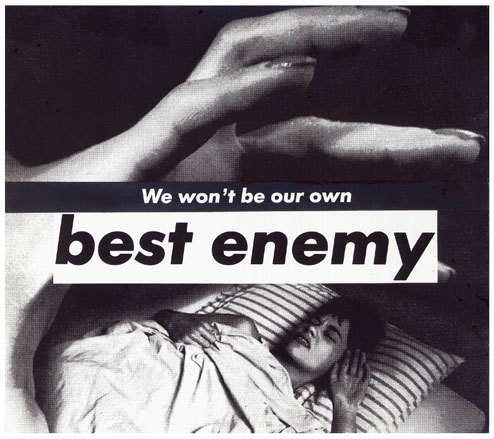

We can add to that list the participants in Ezra Klein’s Journolist. In early 2007, Washington Post journalist Ezra Klein started the e-mail forum to discuss politics with colleagues and acquaintances off the record.According to Klein, the list was meant to use the Internet’s connective capacities to create “an insulated space where the lure of a smart, ongoing conversation would encourage journalists, policy experts and assorted other observers to share their insights with one another.” Membership gradually grew to include 400 prominent writers, editors, academics and reporters, for whom the list was something of a safe haven – a place to talk without the burden of adding to the public record or putting their career at stake.

But in a trackable, Googleable, searchable world, it has become very easy to speak one’s mind, but increasingly difficult to change it. Journolist was originally meant to remedy this. Its informal, spontaneous, and spirited e-mail discussions ranged from health-care reform to foreign policy to local news. Though most members admittedly leaned toward the left, they still frequently disagreed. This isn’t to say that the list was a raging hotbed of disputes and denunciations — Politico’s Walter Shapiro compared it to “cafeteria chatter.” Journolist, after all, was an e-mail listserv, tedious to read and all-too-easy to ignore. Even so, Journolist allowed members to test out half-baked ideas for soundness before transferring their thoughts to their columns, articles, blogs, or lectures. Privacy, wrote Klein, was “essential” and could “only be guaranteed by keeping these conversations private.”

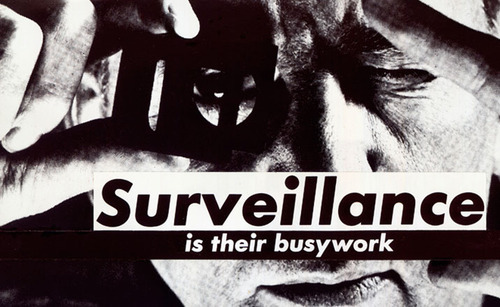

The list was active until early this summer, when an anonymous member leaked to FishbowlDC and The Daily Caller, a conservative online journal, strings of emails that Washington Post reporter Dave Weigel had written to the group. Weigel’s private messages, as well as retorts from other members, were published without context, purporting to expose Weigel – who had just been given a Post column — as biased and unfair. Enraged conservative commentators labeled Journolist a “liberal conspiracy.” Weigel resigned (he now writes for Slate.com), and Klein shut down the forum the same day. Journolist’s downfall suggests that despite the frequent celebration of the Internet as an interactive, democratizing medium — a digitized public sphere, a meritocratic forum of ideas – it is a medium that never forgives, and never forgets.

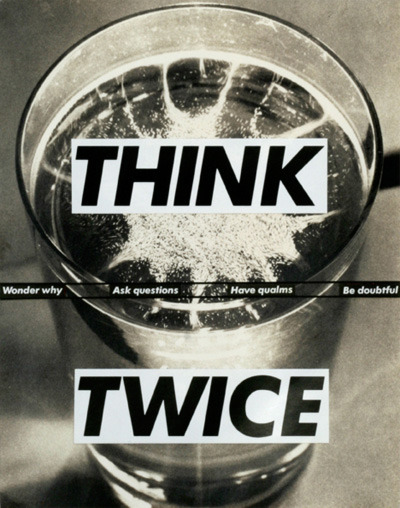

Imagine that you are struck with a curious and rather outlandish thought that you don’t necessarily want to defend for the rest of your life but nonetheless feel compelled to share — if only to see how others react. You write an impassioned paragraph detailing your idea but pause before posting the entry online. Without an editor, you are the sole judge of the quality of your work, and you are aware that by hitting the “publish” button, you would be subjecting yourself to possibly harsh, often anonymous criticism. You must take into account the Internet’s systemic indelibility: that henceforth your entire intellectual stance could be defined by a single, possibly ill-conceived argument.

So you vacillate between killing the conversation before it begins or risking becoming “misrepresented and burned,” as Rosen puts it. Inevitably, this ends in some form of self-censorship. Not every form of online self-censorship is necessarily harmful — if people stopped documenting such things as the intimate details of their breakfast, society would hardly be worse off — but aside from oversharing, what will happen to plain sharing? Withholding inane tweets or provocative photos is one thing, but what will become of intelligent exchange and thoughtful conversation?

In 1981 Jürgen Habermas outlined the ideal circumstances for speech in the “common competitive quest for truth.” Every competent actor must be able to take part in a discourse, introduce and question every assertion, and introduce his attitudes, desires, and without any internal or external forces preventing him from doing so. But because the Internet never forgets, these conditions are impossible to recreate online; its restrictive forces exist not just in the moment but in the indeterminate future too. As a result, ideas become crystallized, locked in time, and indelible.

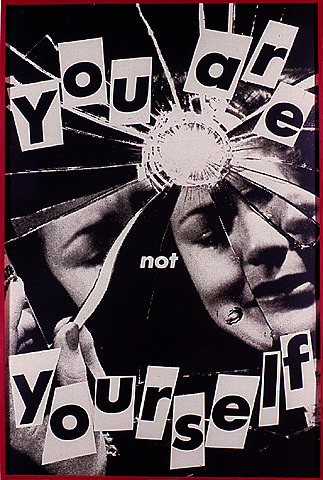

But ideas are not by nature static; to think and to discuss is to invariably change one’s mind. When mercurial acts of spontaneous thinking and feeling move online, they become not just a matter of starting a conversation and nursing a spark of thought between people, but a matter of brand-building, networking, even dating. Online, ideas are permanent; they have no room to change or grow. In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere Habermas argued that individuals need an element of inconsequence in order for ideas to “become emancipated from the bonds of economic dependence.” But at present, ideas are currency, and their exchange a calculated and Machiavellian act.

The online forum is thus overwhelmed by the monetization of information. The lure of instant publication and the dizzying proliferation of gossip gone viral are hard to resist; most publications, hungry for content and desperate for traffic, have no qualms about printing invasive material. This leaves us in an Orwellian atmosphere of suspicion and betrayal. If confidentiality is contingent on not receiving a tempting enough offer, whether it take the form of money, notoriety, or the thrill of shaping Twitter’s trending topics, then who really can be trusted with our digital communications? Post-Journolist, the idea of “private e-mail” is beginning to sound like an oxymoron, and the mandate of constant self-censorship is spreading accordingly.

An example of online mundanity can be found in social media platforms like Tumblr. Tumblr is organized hierarchically – blogs are not valued for the quality of the ideas, but for the amount of “followers” and “re-blogs” they receive. Until recently, users were even ranked by their “tumblarity” – an index based on how much content was generated and re-generated. This encourages the proliferation of unchallenging content, often in the form of puppy photos, 1990s nostalgia, and snark – in short, mere entertainment. Ideas that ought to be seen once and destroyed are now produced at an alarming rate, but no longer have the privilege of disappearing.

If we want to encourage the exchange of ideas, we should not worry, at age 24, if what we say tomorrow will be of any particular consequence ten years later. The need for a private space for conversation without the weight of the web-wide world on our shoulders is more pressing than ever. We need a space to ask questions that Google already has the answers to; where it’s alright make comments only to later take them back; where it’s encouraged to agree, to disagree, to argue, and to play devil’s advocate, all for the sake of the argument. Now more than ever, we need a room of our own to change our minds as often as we choose in good faith.

The concept of the salon – the original journolist, if you will - is a viable alternative to online idea-sharing. Habermas used French salons from the 18th century as examples of “organized discussion among private people” to counteract the insidious forces of the mass media (which, at the time, took the form of our beloved free press.) Loosely guided, spontaneous discussion amongst friends and acquaintances will do more for our minds and imaginations than any number of re-blogs and re-tweets; it will offer a means to counteract the Internet’s “chilling effect” on all peoples’ expressive capacities, and the resultant foreclosure of personal and intellectual serendipity, new ideas, and creative connections. Getting off the Internet might seem a regressive, conservative, and dull suggestion; it is, by all means, a disappointing conclusion to a great experiment in human connectivity. But it is necessary to take conservative action in the name of progress. A small step back could make room for many great leaps forward.