The imaginary guns that white people perceive in black hands reveal a longstanding fear of black resistance

On a recent road trip we made a stop at gun range in Austin, Texas. I posted a picture on Instagram of myself aiming a Beretta pistol down the range, and a white friend posted a comment that read, “You’re scaring us.” The picture had no menacing intent; I felt it joined many images of men, women, children and even blind people with guns. This Instagram comment may have come from a sincere place. But it made me think about how guns are viewed in black hands.

Imagine a sweaty muscular white man kicking a door off its hinges with two machine guns in his hands. He pulls the triggers, massacring everyone in the room. Out of context, this moment is psychotic and disturbing. But reflected off many faces, premiered on televisions and smartphone screens, appearing in countless action movies, thrillers or even comedies, this Hollywood scene is a reflection of a nation with around 270 to 310 million civilian firearms. That’s the most in the industrialized world. It’s inevitable for children to look up at adults and want to gesture guns with their fingers, or play with water guns, paintball and laser-tag. In Cleveland, Ohio, police responding to a 911 call found Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy, playing with an empty BB gun. He was shot and killed two seconds after the police arrived.

At a young age I was taken away from my parents because of their drug addiction and put into the custody of my grandparents. I remember the pictures on their living room wall: a drawing of Martin Luther King Jr with a quote from his “I Have a Dream” speech; a reproduction of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper, and a portrait of an uncle stone-faced in fatigues. His portrait stood out. My parents were the misfits, the perceived embarrassment, so my own immediate family was nowhere to be seen on the wall. To my young eyes it seemed that my uncle had gained the respect of my grandparents and his military service gave him the honor of being displayed near the last supper with Jesus and a portrait of our great-great grandmother.

There are guns everywhere. There are black soldiers, black gun-store owners and black gangsters, and there are white bank robbers, white mercenaries and white South American guerrillas. There are the movies Scarface, Terminator and the Hunger Games trilogy. No one will know what Tamir Rice was pretending to be when he was killed because of it.

American guns are meant to represent the white man’s freedom to protect himself from government and from the colored hordes that surround him. As black men living without dignity through slavery, Jim Crow, and discrimination, for many a gun feels like redemption, allowing us to feel momentarily equal to the oppressor who holds all the rest. But this feeling of redemption is fraught with danger: when a black man handles a gun of his own accord, he reverses the gun’s supposed purpose, and white people get scared. Even when black women pick up guns as a last resort against systemic violence from men—women like Marissa Alexander from Florida—they are punished. When Alexander used a weapon to fire a warning shot to frighten her abuser, she was threatened with nearly 60 years in prison, and now must pay for her own tracking bracelet during a two-year house detention. Meanwhile, in a video chat session in 2013, Vice President Joe Biden shared a story about telling his wife to shoot a double barrel shotgun in the air to deter attackers. The most oppressed cannot take such advice. We must remain vulnerable and look helpless, and when we are abused it’s perceived as our own fault. Guns in black hands are seen as a threat to white supremacy unless they are used to fight its wars to protect its property.

While white open-carry activists and white vigilantes are often discussed as mere isolated incidents, the Cliven Bundy standoff in Nevada showed that white militia groups continue to gain new members, practice their aims, and adjust their sights and tactics for a war against black people, Mexican people, and the government—a war that may only happen in their heads. The majority of the armed groups that arrived to Bundy’s aid came from Nevada and California. The latter has the highest number of white supremacist groups in the country: 65. Texas has 49 and Florida has 45. These groups walk through fast food restaurants, K-marts and government buildings armed and ready for violent conflict. Black men are killed over wallets, pill bottles and other items. We are killed by police over imaginary guns.

These dream guns indicate the depth of white America’s fear of black resistance. But black people are allowed to take part “safely” in gun culture if we agree to become the avatars of respectable, state-sanctioned violence, with military recruiters in our high schools and colleges, and police recruiters outside subway stations and unemployment offices. Over the phone I talked to a relative of mine who lives near Atlanta, Georgia. He owns two pistols and now works at an Internet diagnostic company. He served in the Army for over 10 years, including in the airborne infantry and military intelligence. He fought in Panama and in the Philippines. He was also armed security for the largest nuclear power plant in the United States. As an army veteran, he was trained in assault rifles, 40-caliber pistols and other military-grade weapons. Unlike proud white gun owners all over the country, he chooses to remain silent, worried about harassment for being prepared to defend himself in a state that does not have hate crime laws. He didn’t want me to disclose his name. “All my illusions about serving my country… I’m proud to be a combat veteran, but I don’t expect that to protect me,” he said. Black people can be trained to protect our national security, to be snipers, to be killers, yet if we attempt to protect ourselves from a history of violent white supremacy, we become enemy combatants.

Tree-filled parks in Cleveland, housing project stairways in New York City and other inconspicuous places have become police murder scenes. But there are still more guns than police in the United States, which creates a violent gun culture all across the country and among black communities too. As a teenager walking one late fall night in the black middle-class neighborhood of Canarsie, Brooklyn, I faced a real gun. On a quiet residential street a man approached me asking for the time. Then he pulled a Glock pistol on me, asking me to give up whatever I had in my school backpack and my pockets. Instead I gave him an expired bus pass to distract him and then grabbed his gun. Two shots deafened my right ear. As my finger came close to the trigger, the robber tried to bite it off. Grabbing the gun away from me, he ran away, got into a nearby car and drove off. I ran home as fast as could, my finger bleeding heavily, worried he would come back around looking for me. I faced a black man who wanted to rob me and threatened to kill me, but I would not say this is an issue of “black-on-black crime.” Violent incidents occur everywhere, such as the murders and suicides that happen in white middle-class homes. Yet the idea of a special capacity for violence among black people justifies white extreme force against us. The white obsession with “black-on-black crime” implies that black people live in a world of lawlessness and blight that just comes naturally to us. There are many guns in many hands in this country: in the hands of thugs who wear badges, and the hands of the poor with nothing to lose. But surveys from 1973 to 2012 showed that only around 27 percent of black people in the USA say they own guns, compared to 47 percent of white people. The problem is a society that creates predators and prey over and over again.

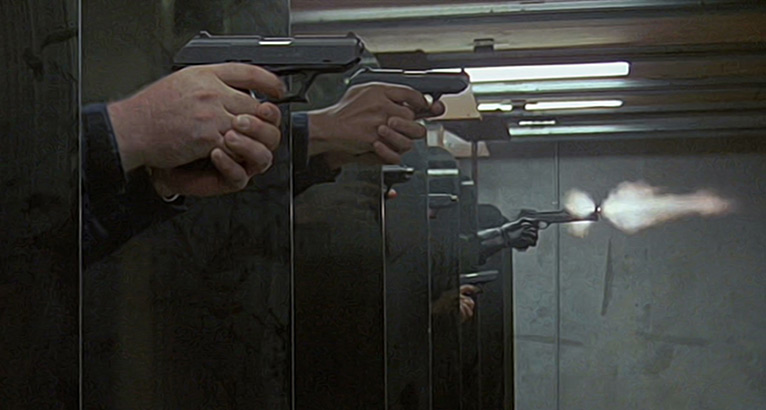

In white war movies like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, and The Deer Hunter, and violent black movies like New Jack City, I'm Gonna Get You Sucka and Boyz in the Hood, the male hero’s gun often operates as extension of his gender, his sexuality, his way of changing the world. A white police officer I imagine lives in this fantasy of power too, maybe takes trips to the gun range, takes time with the family to see the next action flick—we all take part in the exercise of escapism. Obscuring the reality of a poor black USA, a myth persists that there is a gangster enterprise in my community, that police and vigilante heroes must shoot first and the unarmed black victim will turn out to be guilty later. Our lives are the price of escaping reality. The Hollywood illusions of shooting to injure, shooting hats off of heads and cigarettes out of mouths are not what happen when people believe they are in a life-or-death situation. I have fired real guns and from this I know that when you aim, it’s to kill.

As a boy scout shooting BB guns, I was in a space where it was safe to use firearms openly. My black scout troop was among a majority of white ones. I was praised by white boy scout masters for my accuracy and given tips on how to shoot better. As part of a white-approved institution, it was fine for me as a teenager to hold and fire something that looked just like a real weapon. In Ohio, 23-year-old John Crawford was shot and killed by police on sight while holding a BB gun in a Walmart aisle. I performed the same task as John Crawford while visiting Georgia years ago. I walked into a Walmart, bought a long barrel Daisy BB gun and left. The gun was too big for a shopping bag so I walked through the parking lot, armed to shoot bottles on a country dirt road in Georgia. My naivety sheltered me from the reality that I too could have been killed—killed with a last thought of innocence in a culture that heralds guns, torture and war in billion-dollar-grossing video games.

The violent state promotes the idea of non-violent protest but we can’t imagine all of the guns in the USA away with banners and chants. A black America lives in the midst of a white one that aerial-bombed a black town in the 1920s, shot at black protesters in the 1950s and worked to dismantle the Black Panther Party in the 1970s, an overwhelming force that continues to prevent a community from protecting itself even when our calls for justice and equality are non-violent. I believe the imaginary guns that white people use to justify the murder of black people may one day manifest real guns into disgruntled, confused or even organized hands. Maybe my fascination with guns is strange. But America: so is yours.

Comments are closed.