—Gikuyu Architecture

"Your silence will not protect you"

—Audre Lorde

1. Of Public Bodies, Bodies in Public & the Body Politic

In 1922, Mary Muthoni Nyanjiru led a group of women that stormed a police station in Nairobi, Kenya, to demand the release of the nationalist leader Harry Thuku who had been arrested and detained by the colonial government. The colonial forces had guns and the men who had come with Nyanjiru and the other women were afraid. Nyanjiru denounced these men as cowards, stripped naked to shame them, and walked into the police bayonets. She was among the first to die in the ensuing bloodbath, but her bravery roused her people into active resistance.

In 1992, Wangari Maathai led a group of women that occupied “Freedom Corner” in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park, demanding the release of political prisoners arrested and detained by the Moi regime. The government sent armed police to evict the women, who stripped naked in protest and defiance. Wangari Maathai was beaten unconscious and hospitalized, but the women of Freedom Corner eventually won.

Kenyan women have been laying their bodies on the line for years. A group of women stripping naked in public is one of our most potent political practices. Women’s bodies work as a potential and latent public space in Kenyan modernity because they usually appear in public only under cover: a frightening secret weapon everyone knows about. In many African communities, there is no stronger curse or taboo upon men than seeing “the mothers naked.” There is no stronger way for women acting together to register political dissent. Deployed in this way, women’s bodies have the power to make (something) public, to create “a public” around this action, and thus to produce both public-ness and publicity from the ground of their own corporeal materiality.

As political action, this is not only a public mode of power and a specific form of public voice. It is also a critical public voice of dissent against the all-encompassing patriarchy.

These women’s bodies are subversive bodies. Women’s power deployed in this way can only be oppositional, always a challenge, always-already embodying and performing the power to refuse. Yet, women’s bodies do not have to be unclothed for significant utterance. A woman’s daily clothing is already a mode of speech about her life and about her relationship to the situation of her embodiment. In contemporary Kenya, even the banality of women’s everyday clothing appears to pose a threat to masculinist domination.

The Kenyan post-colonial social contract is not a political agreement between allegedly neutral individual citizens but a patriarchal and ethnicist order based on the domination of all Kenyan women by all Kenyan men. The seemingly unsayable political problem in Kenya is the post-colonial dominance of the patriarchal ethnic Gikuyu elites, whilst the ethnic virulence of Kenya’s patriarchal politics threatens our constitutional democratic opening. The bodies of women speaking from different horizons of political possibility create generative conditions of dissent and democratic renewal. It is very much to my purpose to pay homage to the lineage of Gikuyu women’s political protest, in which I include the historical acts of Muthoni Nyanjiru and Wangari Maathai and of contemporary women who continue to use their bodies powerfully.

In 2008 Kenya’s Post-Election Violence, Rachel Kungu, protected only by her commitment to the work of social repair, walked up to barricades of burning tires erected by angry, armed, and violent young men, to negotiate for peace. In May 2013, Muthoni Njogu wrote a poem the day after she participated in a demonstration outside Kenya’s Parliament:

yesterday, i was hit.

yesterday, my heart, hurt.[…]

right now.

there is a swelling at the back of my right leg,

beneath the ankle,

i cannot sleep.[…]

nothing prepares one to be on the receiving end

of a riot police baton.nothing prepares one to sludge through itchy

eyes, coughing phlegm

& seemingly random state of confusion hours

after the violent dispersion.nothing prepares for the experience of running

solo

while a band of armed, club welding, tear canister

holding men run after you shouting for you to

stop.

I oppose the exclusionary and false Gikuyu-centric narrative and the ideological erasure of the many other ethnic communities in the Kenyan story as told by Gikuyu men. Here, I also want to insist on the strong tradition within Gikuyu women's culture of resisting tyranny, oppression, domination, and hubristic upumbafuness by the men. The multi-generational trajectory of Gikuyu women’s political embodiment and ethical public action contradicts the version of Gikuyu culture enforced by misogynist male interpreters and patriarchal narratives.

I use layered juxtapositions of "bodies" and "publics" and the metaphorical sutures between corporeal bodies and "the body politic" to look at how public space has been marked and defined, which bodies impose their forms on the public, and which other bodies are denied a public presence. These questions are not only theoretical concerns. Having endorsed Majubaolu Olufunke Okome that “as a woman, there are conditions under which one is legitimately able to exercise power,” I also mark the violent masculinism acting in the name of public "decency" which has launched a pedagogy of violence and terror against Kenyan women using women’s bodies as its teaching instrument.

These "lessons" are administered through public media showing public spectacles enacted in public spaces and fueled by public commentary. Kenyan public spaces are defined and punctuated by monumental forms of homage to powerful men while by contrast an imaginary symbolic woman without a body who used to represent social justice is now said to be dead. A suggestive resonance links Kenyan forms of masculinism to the spaces and artifacts of Kenya’s patriarchal domination by ethnic political elites.

2. Entanglements & Ululations: A note on theory and methodology

Micere Githae Mugo:

Where are those songs / my mother and yours / always sang / fitting rhythms / to the whole / vast span of life/? […] Sing Daughter sing […] sing/simple songs/for the people/for all to hear/and learn/and sing/with you.

—Where Are Those Songs?

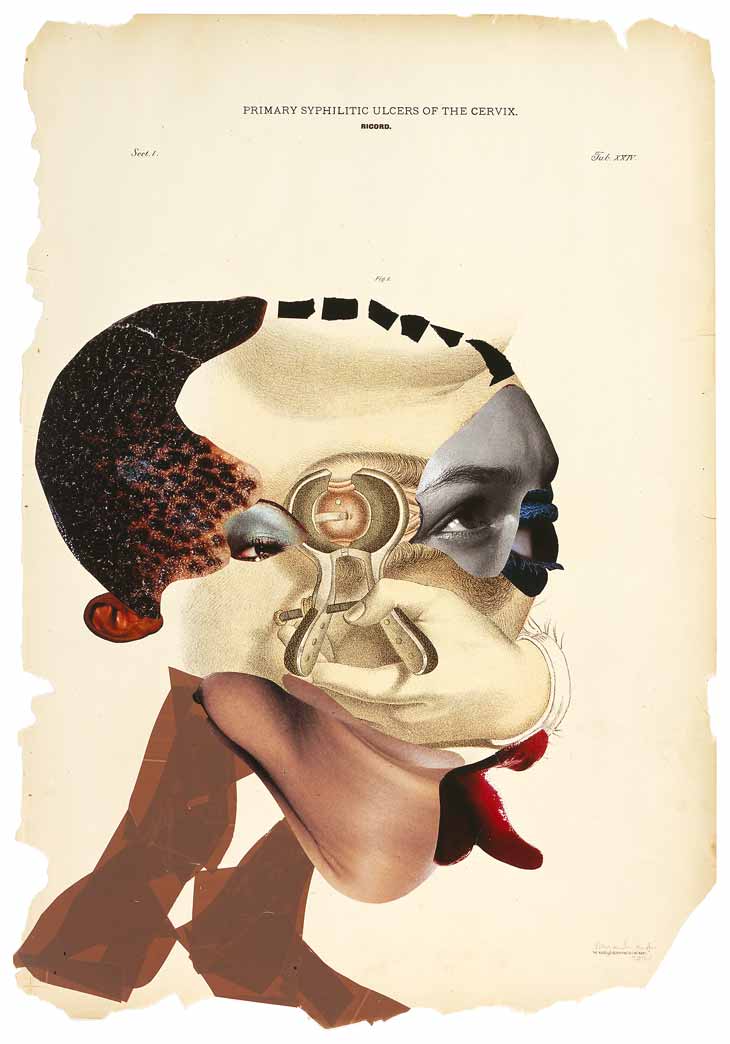

Marziya Mohammedali:

Adrienne Rich:

Whatever is unnamed, un-depicted in images, whatever is omitted from biography, censored in collections of letters, whatever is misnamed as something else, made difficult-to-come-by, whatever is buried in the memory by the collapse of meaning under an inadequate or lying language — this will become not merely unspoken, but unspeakable.

—On Lies, Secrets, and Silence

Sitawa Namwalie:

Let’s speak a simple truth:

The average man can

without much planning

take by force

most average women in the world,

all average children

—Let’s Speak A Simple Truth

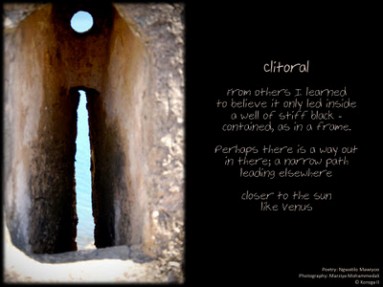

Ngwatilo Mawiyoo:

Ng’endo Mwangi:

First, it is thought. Like this, do you see? Then it is found. Like this. Then it is spoken and said in this way. You do it just so, like this and here, just so. After, it is sewn. Do you see? Like this. When it is built, then it is sung. Now, you try.

—Life

3. In The Name of The Father and of The Son and of The Ethnic Spirit

“It’s a father’s duty to give his sons a fine chance.”

—George Eliot

In Kenya, the business of politics is patriarchy. All the bodies that matter are male and the “House of Mumbi” is a congregation with a powerful political punch. The Republic of Kenya has had four presidents in the 50 years between 1963 and 2013. Three of Kenya’s four presidents have been from the Gikuyu ethnic community. The first was Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, who assumed power in 1963; in 2013, Uhuru Kenyatta, his son, moved his lineage back into a State House first occupied by the man known in life and in death as the “Father of the Nation.”

In Kenya, control of the state means control of the patronage on which the political elite’s accumulation of public resources depends. The crucible of Kenyan politics is the capture of the state by a constellation of Gikuyu elites, their relatives, and their financial cronies, the resulting Gikuyu dominance in politics, economy, and society, and the consequential Gikuyu ethnic privilege. The political hegemony of the Gikuyu community and the Kenyatta family’s dominant position within it combine to create both a deeply ethnicized and also a near-personalized relationship with the state.

Thus, in Kenya, the public is privatized as the political is ethnicized.

2013 is Kenya’s 50th Jubilee, celebrating 50 years of freedom from colonialism. In Kiswahili, “freedom” is 'Uhuru.' In the capital city Nairobi, there is an Uhuru park, an Uhuru highway and now, an Uhuru president. The “Jubilee Coalition” was Uhuru Kenyatta’s political vehicle for his presidential campaign. When Jomo Kenyatta was president, his face was on the Kenyan currency. It still is. Jomo Kenyatta's official photograph was prominently displayed in every Kenyan office and home. In the manner of such power, it came to pass that the largest airport in Kenya is Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. The iconic Nairobi landmark is the Kenyatta International Conference Center, the largest hospital is Kenyatta National Hospital, and a major road bifurcating Nairobi is Kenyatta Avenue. There is both a Kenyatta University and a Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

This metonymic association between “Kenya” and “Kenyatta” is no accident. The first president gave himself that name. He was also the author of Facing Mount Kenya, which he wrote as his doctoral dissertation in anthropology and in which he examined at scholarly length the working of Gikuyu society and cultural practices. This work is so iconic in post-colonial Gikuyu culture that now it does not so much describe as generate Gikuyu identity. In the Gikuyu language of Jomo and Uhuru Kenyatta’s core supporters, “mutumia” is one of the generic words for a woman. The literal translation of “mutumia” is “the silent one” or “one who does not speak.”

Melissa Williams cogently argues that “if justice requires the expression of the different experiential perspectives of different social groups, then one must go a step further to argue that justice requires that these different voices be heard and responded to.” Similarly, according to Aristotle, a political being is a speaking being. Political participation requires the possession of a “voice.” The valorization of women as silence by Gikuyu culture raises questions about their political participation in the democratic processes of post-colonial Kenya.

The usual gloss of ‘mutumia’ is that Gikuyu womanhood is a reserved dignity and composed serenity. This gloss is unsurprisingly the one enforced and circulated by patriarchal and misogynist cultural interpreters. The natural condition of a woman is to dwell in silence, to persevere mutely, and to communicate speechlessly. Silence becomes a woman. Silence is what a woman, in be-coming a woman, becomes. Silence is becoming in a woman because silence is the be-coming of a woman. A woman is silent. The presence of a woman is the presence of silence. Silence is a woman.

Moreover, Gikuyu women are encouraged to misunderstand the mytho-political significance of Wangu wa Makeri, the powerful matriarch who once briefly ruled the Gikuyu. We are told that Wangu was overthrown because the men plotted to impregnate all the members of the women’s council simultaneously. The implicit rapes necessary for this forced synchronicity of pregnancies notwithstanding, we are also taught that nine months later these same men staged a noble coup d’état and Wangu’s viciously oppressive matriarchal rule was ended, forever.

This carefully circulated and re-narrated cultural "knowledge" re-inscribes alleged contradictions about women’s bodies, power, and political possibility. It reminds women that all our bodies are always available for physical degradation by all men. It threatens while inscribing the illegitimacy of women in political authority. It destroys the public power of women’s bodies by destroying women’s power to use our bodies in a public way. It inscribes the collective memory of matriarchal rule with the mark of illegitimacy and perversion. This repressive discursive construct supports Sylvia Tamale’s perceptive demarcation of women’s cultural history as a rights-infused territory of potential justice-claiming publics and publicity precisely by the vehemence with which it denies such a possibility.

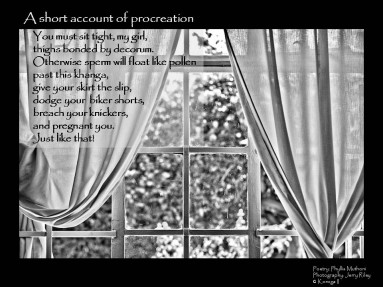

Phyllis Muthoni:

4. The Pedagogy of the Body Strippers

Matatus are Kenya’s predominant form of public transport. Matatus drivers are infamous for their aggressive driving style, propensity to speed (and crash), and their hostile and dominating attitudes to almost every other type of vehicle and road user. Either despite or because of these frightening aspects, these matatus—especially driven in this way—are also iconically Kenyan. Matatu stops and vehicles are a dynamic public Kenyan space. They are where all Kenyans meet, mingle and often deliberate our politics in the course of our ordinary lives. Matatu culture is also belligerently masculinist. As Keguro Macharia observes, violence against women in Kenya is so entrenched as to be unsurprising, un-extraordinary, banal.

In January 2013, a 13-year old girl returning home to Dandora in a number 42 matatu was abducted by a group of men who took her to an unknown location and gang-raped her repeatedly. On the 16th of February 2013, the Nation Television Network reported that a woman had been attacked and stripped “by matatu touts” at a bus/matatu-stop in Kitengela, a town in Eastern Kenya. The reporter said that while the lady escaped relatively unscathed from the incident, she “did not seem remorseful.” The reporter also interviewed the area parliamentary representative, who described the incident as “shameful” but “urged women to dress more decently.”

On April 1, 2013, a woman passenger got off a matatu at the bus stop in Nyeri, a town in central Kenya, and was assaulted by men variously described as “a group,” “a crowd,” “a mob,” or simply as “matatu touts.” The media report was that the woman was attacked and raped because the men judged her “indecently dressed.” The “matatu touts” tore off her outer clothes, ripped apart her underwear and forcefully inserted their fingers, sticks, mud, and dirt into her genitals. They taunted her that they were helping her achieve her goal, as the way she was dressed showed that she had wanted to show off her body.

Kenya learned of this incident because it was broadcast on national television and the video was placed on the network’s website. After protest from individual women and women’s groups, this casual depiction of humiliation was replaced with a marginally less alarming video of other women helping the shattered victim salvage her belongings. The text under the adjusted video clip reads:

Drama ensued at the nyeri bus termini when a crowd descended upon a lady they claimed was indecently dressed. The angry mob undressed the lady saying that the short dress top she had worn reflected badly on the women of nyeri. the lady who was not given a chance to defend herself was stripped and left in her birthday suit as her inner garments were kicked and thrown about by angry men. The women who were equally scorned warned mothers against letting their daughters leave the house without approving their dressing. A good samaritan who witnessed the saga saved her embarassment by giving the lady a long dress as an alternative approved by the men. [sic]

In the adjusted text, these words were removed: “Traders and other passers-by had a free movie to watch as they gathered to witness as the drama was unfolding…Women and mothers were warned not to let their daughters walk out of the house without their approval. What a lesson!” Like most of the world’s corporate media, Kenyan news-media anticipates and transmits to a dominant male gaze. The on-air anchors displayed an unattractive admixture of prurience veiled by spurious professionalism. The framing of this incident suggests, also, that a submissive female public—the everywhere-threatened subject of violence—is not so much anticipated as in the process of construction. This incident is not likely to be the last in Kenya; nor has the public lesson been lost.

Eight days after the Nyeri bus stop attack, another story appeared about a woman who was attacked by “matatu touts” in Bomet, a town in Kenya’s Rift Valley. The touts said the mini skirt was offending and prompted them to strip her as a lesson to other women. According to the newspaper report:

‘This is how women end up being raped and men are blamed for being immoral yet women dress in a bad way,' said Kiprono Sang one of touts.

At time of writing, there have been no arrests of any of the perpetrators in these cases.

5. Burying Wanjiku: Mystery! Woman’s Body Missing Before Her Death!

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive—Audre Lorde

Social justice activist Rachel Gichinga observed that women "got a shellacking" in the March general elections. She was referring to the minuscule numbers of women elected to the national legislature, but her observation also applies in unexpected domains. On the day after the Supreme Court of Kenya affirmed the victory of President Uhuru Kenyatta, columnist Rasna Warah published an article in the Daily Nation entitled “Wanjiku is dead but who will mourn her when everyone wants to move on?” As she wrote:

Wanjiku died last week. There was no state funeral, no wreaths, no eulogies. She was buried in a quiet ceremony in her small plot of land. They say she died of a broken heart. A note was found next to her body. It read: ‘I am tired.’

When the villagers learnt of her passing, they shrugged and said: ‘That is life. We need to move on. We can’t mourn that which was never ours.’

Warah ensured that we remembered Wanjiku by claiming that we had forgotten her.

To 're-member’ is to make a member again, to bring that member back into the community of imagination, re-awakening past trajectories and giving new momentum along new paths of the present. More prosaically, if your name is in the headline of a nationally-circulating newspaper, you are re-presented, recalled from absence and made present again, millions of times.

Warah’s readers seemed to be acquainted with Wanjiku. The comments section was immediately filled with vigorous dispute about Wanjiku’s health and death. Wanjiku was alive and kicking, and had been seen at a Nairobi market that very day; Wanjiku had indeed died un-mourned and in vain; Wanjiku was dead but not forgotten, the whole country was grieving for her; Wanjiku might be in a coma and would yet recover in a few months or in five years.

Wanjiku is—or was—an iconic representation of “the ordinary Kenyan citizen.” Kenyan artists, intellectuals, activists, lawyers, and politicians invoke her to make arguments in “the public interest” or “the common good.” Wanjiku is Kenyan shorthand for our ‘we.’

In the 1990s, President Daniel arap Moi dismissed popular pressure for constitutional reform by demanding, “What does Wanjiku want with a constitution?” Unwittingly, he created the defiant symbol: Wanjiku was enthusiastically adopted by proponents of constitutional reform as the “anti-Moi.” They demanded social justice and a new constitution on her behalf. Wanjiku became ubiquitous in the Kenyan public imagination, a way of gesturing to “public opinion,” the “common person,” or the “ordinary mwananchi.”

“Wanjiku’s Constitution” passed by national referendum in 2010. Chief Justice Willy Mutunga keeps a half life-size sculpture of Wanjiku on display in his chambers because, as he put it, “Wanjiku is the boss.” The sculpture shows Wanjiku with a copy of the constitution in her kiondo (bag). Gado, the prominent political cartoonist, frequently includes Wanjiku in his satirical images. She is a tiny figure in the corner, commenting wryly on political antics and the quirks of Kenyan society.

Wanjiku represents, or represented, the people whose names never appear in news broadcasts or newspaper pages. She was the voice of those who are subject to the actions of the powerful but never powerful themselves. She was alert to the rising costs of living and the quotidian preoccupations of daily life. Wanjiku was thus the private citizen with a view of public actors, the powerful and famous. By commenting on social trends, Wanjiku was a private critic of the public, of the generalized “society out there.” In this sense, she manifested as the unacknowledged instability between "public" and "private" concerns. As a figure of the democratizing aspirations of a new constitutional order—but attentive to the concerns of its citizens—she straddled the divide separating the valorized and masculine public world from the comparatively undervalued private female world. She was easily translatable into different contexts. Her persona was down-to-earth. Performance scholar Mshai Mwangola observed that Wanjiku "came across as a favorite aunt."

However, Wanjiku’s emergence in the male-dominated Kenyan public sphere didn’t necessarily imply more equitable gender relations, or even awareness to gendered issues. In her translation to a visual form, after all, both the cartoonist and the sculptor are male. The imaginations that shaped Wanjiku for national representation have mostly belonged to men. Wanjiku seems to lack any awareness of her body’s processes—such as menstruation, pregnancy, or the need to eat—and she also has strangely male-inflected concerns. The Kenyan universalism she portrays is coded male.

Not having a body, Wanjiku is unable to experience or mediate the lived politics of a body’s situation and concerns. Without a body, Wanjiku is only a name. Wanjiku might be failing as a avatar of social justice because her name places her in Uhuru Kenyatta’s Gikuyu community. As an angry Kenyan voice proclaims, “There is no Wanjiku in Kisumu.” Kisumu has historically been a bastion of opposition to Gikuyu ethnic hegemony and thus to the Kenyatta family’s rule. The experiences Wanjiku purported to represent are lived experiences by real women’s bodies in the corporeal situations of real women’s lives. Perhaps this Kenyan riff on “Lady Justice” invites resistance to the making of a Kenyan every-body or Kenyan any-body out of an ethnically specific but poignantly disembodied no-body. Perhaps, instead of personifying a national aspiration to social justice, Wanjiku served or was perceived as a disciplinary site for the domestication of gendered and ethnicized dissent. Even so, the traces and cleared spaces of Wanjiku’s possible failure might generate alternative pathways to a more shareable Kenya and a more livable way of building our common spaces of the ordinary.

6. Kethi Kilonzo and The Shackles of Doom

And you shall not escape

What we will make

Of the broken pieces of our lives.

—Abena Busia

In a departure from Wanjiku’s impassive ubiquity, a different Kenyan womanhood has captured the attention of the Kenyan public. Almost by definition, women who make news tend to be not-ordinary and not-average. These extraordinary women in the public eye stand implicitly as the antithesis to Wanjiku, whose power rests in her ordinariness. The Kenyan public’s awareness of these women ironically also includes knowing that they are not-ordinary because of the structural constraints and prohibitive contexts under which and despite which these women have emerged into public visibility.

Kethi Kilonzo argued the petition challenging the validity of the electoral process before the Supreme Court, and though she lost her case, she gained an enormous goodwill constituency. A lively public of supporters, admirers, legal groupies, legal peers, and admiring well-wishers that has been drawn into each other’s orbit by Ms. Kilonzo's affect might sketch the contours of an audience for alternative politics. Watching Ms. Kilonzo before the Supreme Court, I was struck by the dramatic David and Goliath contrast of the proceedings. Light of build and with a deceptive air of fragile vulnerability, Ms. Kilonzo faced an intimidating coterie of highly experienced and very expensive male lawyers representing the Electoral Board, Mr. Kenyatta, and Mr. Ruto respectively.

As a candidate for the Kenyan public’s affections—and as a symbolic hook for constitutional justice—Kethi Kilonzo’s presence in the landscape of the Kenyan imagination might offer several advantages over the Wanjiku Effect. Wanjiku, supposedly an "ordinary" citizen, is possibly either opaque or ethnicized. Kethi Kilonzo is not an average or ordinary citizen. Her position is privileged and particular. Her late father was once Justice Minister and was also the Education Minister in the just-ended Coalition government. Kethi Kilonzo is as materially substantial as Wanjiku was not; a professional woman where Wanjiku was ambiguously occupied; of Kamba ethnic origin where Wanjiku was redolent with Gikuyu origins; wielding constitution law like a sword in a warrior’s hand whereas for Wanjiku the constitution seemed more of a shield; and flesh and blood articulacy to Wanjiku’s inked outlines and imaginary laconic speech.

Class divisions in Kenya have often been intentionally obscured by the elite’s malevolent ethnicization of Kenyan politics. Kethi Kilonzo’s stance in defense of constitutional compliance suggests one ethical form of broaching this impasse to find a workable common ground. To the 49.03 percent of the electorate who would have preferred a different Supreme Court decision, Kethi Kilonzo now has a powerful political credibility. She raises the possibility that social and class privilege might not determine political destiny. Kethi Kilonzo’s substantive argument before the Court was also material to the emergence of "a public of interest" around the constitutional issues she articulated and until her father’s death, she continued to be a vocal public critic of the decision by the Supreme Court. Kenya might now possesses the kernel of a constitutionally literate public as a result of the enthralled attention to the nationally televised Supreme Court proceedings and to Kethi Kilonzo’s subsequent media appearances.

Another horizon of possibility opens out of a controversy pitting constitutionally embedded hate speech laws against equally constitutionally guaranteed rights of freedom of expression and speech. An original play by Cleophas Malala, Shackles of Doom, entered the Kenya National Drama Festival by Butere Girls High School, and was deemed “hate speech” and banned by the authorities because it depicted and critiqued Kenya’s ethnicized politics. More precisely, the plot is critical of Gikuyu strategies of economic domination. The constitutional injunction against “advocacy of hatred that constitutes ethnic incitement, vilification or others or incitement to cause harm” was pitted against the right to expression, artistic creativity, and academic liberty. Both of these imperatives are enshrined in article 33 of the 2010 Kenyan constitution.

Kenyan social media erupted in vociferous displeasure at the Ministry of Education’s arbitrary decisions and veteran social justice activist Okiya Omtata pursued the appeal before the High Court. Photographs of the students were widely published and circulated, as were ever more detailed engagements with the play’s narrative. Possibly pirated DVD copies of Shackles of Doom found an instantaneous and enthusiastic Kenyan market. The Butere Girls company received several pointedly public invitations to perform at privately-owned venues across the country. The Kenyan Diaspora thickened national Kenyan public discourse with queries and belligerent commentary. All the broadcast media weighed in. The discursive thrum had more political impact than the most successful staged play possibly could. Even from within their enforced silence, these young women’s bodies were articulating a critical facet of Kenyan existence.

The ban was announced a few days after the Supreme Court confirmed Uhuru Kenyatta’s electoral victory. Not many people had seen the play or known about it, and if it had not been censored, most Kenyans would never have heard of it at all. But the news that a high school play had been banned on grounds of causing ethnic offense to or hatred of “a certain ethnic community” generated a storm of public protest and indignation. Artistic creativity in Kenya—especially high school plays—had not been censored since the hateful days of the Moi dictatorship. Activists appealed the Ministry of Education’s ban, and somewhat unexpectedly—given the conservative electoral ruling handed down by the Supreme Court—the appeal was successful. The play was unbanned. Judge David Majanja’s ruling held that:

Artistic expression is not merely intended to gratify the soul. It also stirs our conscience so that we can reflect on the difficult questions of the day. The political and social history of our nation is replete with instances where plays were banned for being seditious or subversive. This is the country of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Micere Mugo, Francis Imbuga, Okoth Obonyo, and other great playwrights who through their writings contributed to the cause of freedom we now enjoy. Some plays were banned because they went against the grain of the accepted political thinking. Kenya has moved on and a ban, such as the one imposed by the Kenya National Drama Festival must be justified as it constitutes a limitation of the freedom of expression. I am not convinced tat Kenya is such a weak democracy whose foundation cannot withstand a play by high school students.

I certainly endorse Judge Majanja’s sentiments, yet, the Butere Girls’ play had already achieved part of its purpose even while the girls and their play were absent from public view. This attempt to remove young women from staging an interrogation of Kenyan society and articulating new political possibilities failed because the public push-back against the ban was instantaneous and impassioned. This was neither a particularly gendered response nor based in explicitly gendered concerns. Nevertheless, these young women’s silenced bodies stirred a public to intervene on their behalf.

Gwendolyn Bennett said, “silence is a sounding thing for one who listens hungrily.” Listening hungrily, I hear women’s bodies speaking in and through the silence. Kethi Kilonzo lost her case, and the Butere Girls did not win a prize at the festival, but as have many Kenyan women who have enacted protest and dissent under conditions of political duress, both created a visible and vocal public by the focused performance and non-performance of their bodies. Generations of Kenyan women have used their bodies to create a new collective imagination and to nurture justice in our political community by showing nakedness, by offering bodily truths and by converting corporeality into transformative speech. As I tell you these stories now, my own back is curved over my desk. My eyes are tired and my arms are cramped. I feel the tension in my neck and between my shoulder blades. In the silence, I hear the loud clatter of my fingers on the plastic computer keys. I hear the songs of my mothers and my sisters. I hear my voice.