An orphaned moppet in pursuit of a daddy, a pet in search of a warm lap, no one is more a child than Shirley Temple losing value

It takes a great deal of effort to manufacture and maintain any star persona, and that labor is particularly stark in the case of children, who grow tall, lose their baby teeth, and shed the babyish manner that is at the core of their appeal to audiences. Childhood is ephemeral by nature, and the specter of obsolescence haunts every child performer.

Shirley Temple’s persona was more or less frozen at six years old. At the moment of her earliest success in 1934, Temple had exactly 56 golden ringlets, round eyes, chubby cheeks, and stocky legs.

The first image in the 1935 film Curly Top is that of a child’s overturned head of glossy ringlets. Holding her head still for a beat, the child looks up, gazes into the camera, and breaks into a toothy, dimpled smile.

In continuous close-up, she shakes her head of curls for several seconds and giggles, never once looking away from the viewer. Temple is the only lead actor whose name doesn’t flash atop her still portrait as the credits roll — it appears marquee-style above the name of the film — but it doesn’t matter, of course. By 1935, Temple hardly needed to be introduced by name. Her face and curls identified her readily enough, just as they more or less embody the plot of Curly Top and most of Temple’s other movies: a small child performs her cuteness for us in a variety of locations, and we cannot look away.

The legend of Shirley Temple, who died on February 10 at the age of 85, is well known by now. After beginning her career at three years old, Temple became the No. 1 box office draw in the U.S. from 1934 to 1938, and starred in more than 20 highly profitable films by 1940. Her success effectively saved Twentieth Century Fox from bankruptcy, and Franklin D. Roosevelt credited her with perking up Americans at the height of the Great Depression. She remains the youngest performer to have received an Academy Award and one of the greatest examples of effective cross-merchandising in U.S. history. During her reign as box-office darling, Temple’s films were geared toward adults as much as they were to kids. Only in the era of Sunday morning reruns have her films become children’s movies.

But the cute precocious ideal she represents, her wide-eyed innocence and hearty vitality, has also spawned critique. There is a small academic cottage industry devoted to dissecting the troubling sexual politics of Temple’s oeuvre, in which the star appears always as a motherless or orphaned moppet in pursuit of a daddy, a pet in search of a warm lap. Claudia MacTeer, the black protagonist of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, wishes to dismember her Shirley Temple doll to discover the source of its cultural power.

Temple’s first role was as the recurring lead in the Baby Burlesks series of 1932–33. In these deeply exploitative one-reel shorts — they make Toddlers and Tiaras look like Reading Rainbow — she and the rest of the three- and four-year-old performers spoof famous films on a miniature scale, structuring cuteness as the staged collision of opposites: pairing grown up, risqué costumes on top with diapers fastened with huge safety pins on the bottom. Temple shines as Morelegs Sweet Trick, La Belle Diaperina, and Madame Cradlebait.

In Temple’s full-length films from 1934 on, all cuteness lies in similar contrast: Temple wears either short dresses that show off her underwear and emphasize her stubby legs or oversize men’s clothing and military apparel that highlight her tiny size through sheer incommensurability.

All of Temple’s films delight in the visual spectacle of diminutive Shirley craning up her neck to speak to her white male companions, or being scooped up, tossed around, or carried about like a baby. (She danced but never cuddled with Bill Robinson, the black performer who co-starred in four of her films.) Temple’s cuteness is structurally dependent on her being dwarfed by adults and kept remote from other white children onscreen, who studio executives believed threatened to “dilute [her] aura of uniqueness and thereby diminish [her] professional potential,” as Temple herself put it in her autobiography, Child Star. Black children and the tall, dark haired Jane Withers, however, were exempt from this rule. In the racist logic of Temple’s films, these children did not threaten her “aura” at all — they only affirmed it, using the same logic that placed her alongside adult men.

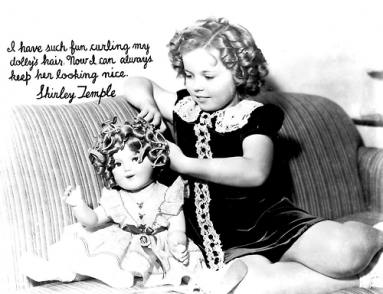

While Temple’s talent was undeniable, her performances in films and in photographs are surprisingly ritualized, characterized by a limited set of gestures and poses that signify as reliable indicators of cuteness. If you have ever looked at pictures of her, you’ll know them already. In print, she raises her eyebrows and purses her lips; raises a know-it-all finger; issues a military hand salute; plays with a toy or small pet; or sits in a dreamy, angelic pose. Onscreen, Temple frequently pushes back her head, implants it in her neck while bracing her shoulders and making several chins, and then shakes her head while making proclamations. She talks though a pout, widens her eyes to signal vitality and “spark,” and of course, she sings, tap dances, and cries real tears like a champ.

There’s an uncanny quality to Temple’s persona that partly stems from the way she repeated these same tropes over many years — Temple’s contract with Twentieth Century Fox stipulated that she pose for studio portraits near-daily, sometimes while also holding a doll that looked just like her.

As a cultural ideal of white childhood perfection, Shirley Temple was heir to a modern understanding of individual children as subject to objectification and comparability, composed of qualities that could be “scientifically” measured, evaluated, and compared. Beginning in 1911, “experts” used growth charts and physiognomic tests to measure infants’ physical and mental development in Better Baby competitions. After the U.S. Children’s Bureau founded National Baby Week in 1914 in an effort to lower infant mortality rates, infants duked it out in Perfect Baby contests — capstone events that relied upon eugenicist criteria of childhood health and beauty. Such standards would help bolster Temple’s status as the smallest and sweetest white girl in the world, and they suffuse the visual culture that surrounds her.

Magazine and newspaper articles focused, often obsessively, on the objective criteria by which Temple had achieved her “perfect” qualities, explaining her diet and exercise regime as instruction for readers hoping to shape their own offspring’s development. One 1938 article from Screen Guide magazine performed a “scientific” analysis of Temple’s physical development, charting her growth and weight statistics against those of the average child. Articles like these insisted that Temple’s curls were absolutely real, each ringlet occurring naturally and requiring no upkeep, and reported on her genius IQ of 155. As a corollary, Temple’s first studio contract skipped over her extensive early training in dance, making her appear like a natural talent with an inborn facility for tapping.

A major conceit of the child star is that because a child’s talent is innate, her work in a film is therefore play. The successful child actor is by definition a natural, her performance as spontaneous and unwilled as it is convincing. (Recall how filmmakers describe the sheer luck of stumbling upon gifted child performers like Quvenzhané Wallis, or Dakota Fanning in her early years.) The media blitz surrounding Shirley Temple erased all visible signs of labor — both the work Temple performed six days a week since she was three years old, and the considerable work that went into training her and maintaining her image.

Historian Charles Eckert has argued that Depression-era discourse demanded that Temple’s labor be overwritten as a narrative of love and play, making her status as a worker “self-obliterating.” And so the mythology goes: Shirley did not memorize lines and dance steps and spend hours posing for still photographs each day — she simply played. Witness Time magazine: “Her work entails no effort. She plays at acting as other small girls play at dolls. Her training began so long ago that she now absorbs instruction almost subconsciously.” Witness Temple’s mother, Gertrude: “I was afraid she would begin to act for me. I want her to be natural, innocent, sweet. If she ceases to be that, I shall have lost her — and motion pictures will have lost her too.” Lionel Barrymore expressed awe at his young co-star “artless art.”

And yet this effort to reinscribe Temple’s work as play co-existed with a media narrative about the economic relief she instigated in the midst of the Great Depression. One article in Modern Screen, “Shirley Temple: Saver of Lives,” describes how Temple’s success put thousands of people on the payroll. She made millions for the film industry and uncountable merchandisers, even if her father lost through poor investing all but $44,000 of the money she made for herself.

Why do we need Shirley Temple to be a miracle? It hardly needs repeating that her image was micromanaged by her parents and Twentieth Century Fox, her birth certificate forged to make her one year younger and thus always apparently in advance of her peers (a fact she learned on her 12th—no, 13th birthday), and her hair rinsed with vinegar and set in pin curls nightly. Indeed, Temple was obligated to do everything possible to keep herself young and innocent. Her 1934 studio contract included clauses meant to pre-empt spoiling, specifying that her co-workers were not allowed to praise her, that she should isolate herself on set from adults who might not be able to resist flattering her, and that she was forbidden to watch films other than her own lest her famous capacity for absorption and imitation should distort her own natural style. If Temple became spoiled, executives reasoned, you would be able to see it in her face.

Even as Temple stuck to her formula and grew as an accomplished actor and dancer, you can see the strain in her eyes begin to outshine their sparkle around 1938. By 10 (9 to the public), Temple had lost all her baby teeth, subtly matured her hairstyle into two pigtails, and grown several inches, and her impression of an adult’s vision of a six-year-old white girl had become unconvincing. The tension is obvious in Temple’s 1938 movie Little Miss Broadway, in which she plays Betsy, an orphan whose singing and dancing saves the hotel she lives in and secures her some parents. Facing the crisis of Temple’s obvious maturation, Little Miss Broadway resorts to desperate camera angles, often angling down at her from extreme heights to exaggerate her childishness as she peers powerlessly upward. Temple’s choreographic strategies remain the same, yet her childish tricks — dancing on tables and countertops, being scooped up and thrown about, generalized cuddling — do not carry the same charge. Betsy simply has no cute power; her powers are more womanly. When she smiles at an older boy and begs him for a nickel so she can take the subway, he grumbles, “Oh, you dames are all alike.”

Temple retired from the screen two years later. Her parents bought out the remainder of her studio contract and sent her to school for the first time. She would go on to make a handful of movies in her teens, but the love affair was plainly over.

As early as 1937, author Graham Greene perceived the end of Temple’s childhood as a crisis of temporality. Greene’s infamous review of Wee Willie Winkie in Night and Day magazine flagrantly eroticizes her — for which he was sued for libel — even as it critiques the way her audience fetishized the young star. And yet it also expresses a curious sense of nostalgia for Temple’s disappearing girlhood. “The owners of a child star are like leaseholders — their property diminishes in value every year. Time’s chariot is at their back,” he writes. Greene adds to this (libelously) that infancy was always Temple’s disguise; with a “well-developed rump,” “agile studio eyes” and a “well-shaped and desirable little body” she had always held a specifically adult appeal for audiences. The “mask” of Temple’s childhood, while clever, could not last.

Nostalgia has always been at the heart of Temple’s appeal, as much at the height of her career as it is now upon her death. Nostalgia, after all, is a kind of resistance to progress; it’s a mode of connecting with a time and place that has never truly existed but which endures as fantasy and which grounds national and cultural projects of all kinds. It’s true that Shirley Temple was a pretty marvelous performer. But nostalgia can be a sinister optic in adult viewers gazing upon the young. All too easily, it cloaks the sexual objectification of children and obscures the role of cuteness as a commodity that is destined to decline in value. Temple was at odds with real time from the start.

She knew it too. “When I was fourteen, I was the oldest I ever was. I’ve been getting younger ever since.”