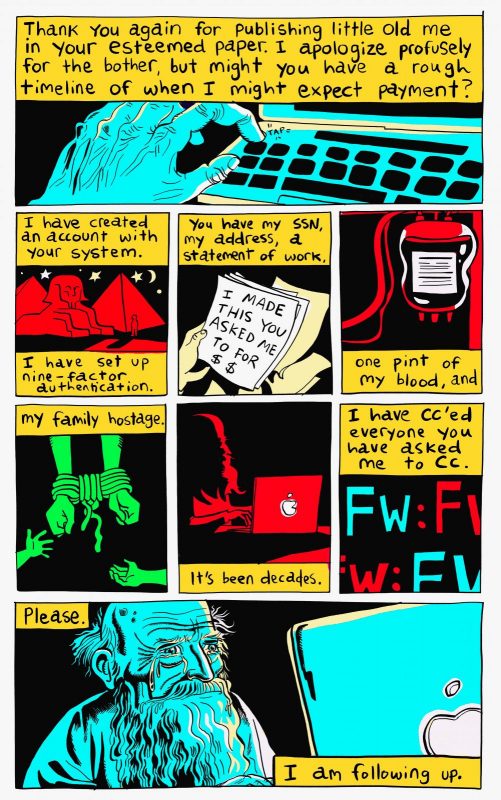

2013 comic from The Knife: End Extreme Wealth

In 2013, Berkeley Professor Emmanuel Saez wrote that income inequality in the United States was the highest it had been since the Great Depression, and due to the modest policy response, “it seems unlikely that US income concentration will fall much in the coming years.” Swedish electronic music group The Knife echoed the same sentiment in a companion comic to their 4th studio album, Shaking the Habitual. To shake up the habitual rhetoric of patronizing, top-down NGO-ified “global poverty” initiatives, the duo worked with artist Liv Stömquist to produce “End Extreme Wealth.” The comic treats extreme wealth as what it is: an increasingly confused symptom of a deeply sick system. In reversing the thematic considerations of an institution like the UN, “End Extreme Wealth” lambasts the unipolar focus of such bodies on poverty reduction without so much as nodding to the co-constitutive phenomenon of wealth accumulation. It also derides the presupposed moral deficiency of people living in poverty in its satirical re-education classes for the extremely wealthy. The comic, and the excellent album that it accompanies, calls for a new type of structural adjustment.

One year of Sex Is as Sex Does

In Sex Is as Sex Does (2022), published just over a year ago, Paisley Currah forgoes decades of trans studies discourse on what sex is to look at how sex is crafted by the state. Currah’s descriptions of state offices like the DMV thus combine tedium and drama, like a soap opera about administration. They are the “lesser noticed (and much less sexy) apparatuses and domains of governmentality that even Foucault found too dull to look into”; they are also sites of muted fear. The DMV, after all, is where name and sex changes are ratified. For trans people, these markers help determine whether you can be stealth at your job, get healthcare, or public space. Like marriage and inheritance laws, the DMV is thus just one of many ways that the state allocates violence and resources.

As Allison Brown notes in her smart and thorough review, the most directly helpful part of Currah’s book is actually his analysis of prisons. While Currah “acknowledges the comparative harm that trans prisoners experience, he emphasizes that there is a much greater gap in treatment between trans non-prisoners and trans prisoners than in the treatment of trans prisoners and cis prisoners.” Discarding a trickle-down analysis of oppression, Currah instead foregrounds prisons as cites of exceptions where, for instance, the invisible hand is substituted for government access to your life. “The reality of the institution of prison is so abject and inhumane that the best policy development for trans people is the same as it would be for the majority: abolition.”

Free Ebook: Can’t Pay, Won’t Pay: The Case for Economic Disobedience and Debt Abolition

In light of the Biden administration's continued mismanagement of the student debt crisis, Haymarket has made this landmark work available for free. The book argues for "economic disobedience" against the debts people are forced to take on in order to effectively participate in society. Predatory student loans and medical debt are both examples of the financial injustices covered in the book, as is the question of undocumented workers’ unpaid wages and people paying for their own incarceration. The Debt Collective was formed in 2012 and this book, published in 2020, offers answers to the crushing economic violence of debt that has only grown in aggression and urgency over the last decade.

Approximately 2400 people have been arrested as France enters the 6th day of protests following the police murder of a french teenager of Algerian descent. On June 27th Nahel Merzouk, a 17-year-old, was shot and killed by a police officer during a traffic stop and police initiated car chase. Since then, French youth of African and Middle Eastern descent have protested state violence with fires across Paris. As of this morning, one French mayor is claiming he was the target of an assassination attempt, as a car was pushed towards his home, eventually reaching an outer wall. President Emmanuel Macron has so far blamed the protestors, postponed a planned visit to Germany, and requested TikTok and Snapchat's aid in suppressing footage from the riots. Following Macron's remarks Snapchat told the BBC "it had "zero tolerance" for content that promoted violence and hatred, and would continue to monitor the situation closely."

If, in alliance with state leaders, tech platforms continue to categorize riots that protest violence as calls for violence, then the public will face greater difficulty in using these platforms as effective communication and information resources. It follows the pattern of American companies like Twitter and Instagram showing leniency to slurs and hate speech, but punishing the targets of both. On Saturday, French police unions released a statement that functionally announced a race war.

They described the ongoing riots as a "civil war," arguing that, when "facing these savage hordes, asking for calm is no longer enough, it must be imposed! Restoring the republican order and putting the apprehended beyond the capacity to harm should be the only political signals to give. In the face of such exactions, the police family must stand together. Our colleagues, like the majority of citizens, can no longer bear the tyranny of these violent minorities. The time is not for union action, but for combat against these vermin."

This word choice echoes the characterization that long preceeded this week's clashes: the year Nahel Merzouk was born, Nicholas Sarkozy successfully campaigned for president by promising to "flush out the vermin," referring to the black and brown youth of France's suburbs, which are largely populated by descendants of nations previously occupied by France. By the time Nahel was four years old, Sarkozy had "declared war" on the urban residents of France, who, at the time, were protesting the police murder of a twenty-two-year-old. Nahel Merzouk was buried on Saturday; at seventeen, he already had fifteen recorded incidents with the police by the time one killed him on Tuesday. A sensitive speaker of English could consider removing the phrase “rule of thumb” from their vocabulary. The term has its roots in domestic violence: a British law stipulated that a man could beat his wife provided he used a switch no wider than his own thumb. This was the history referenced by The Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative in a list intended for use in Stanford University’s IT department, which made the rounds online just before Christmas last year. In a column helpfully labeled “Context,” the authors explained why “rule of thumb” should be nixed from readers’ usage. “Although no written record exists today,” the document reasoned, “this phrase is attributed to an old British law that allowed men to beat their wives with sticks no wider than their thumb.” A similar text—this one circulated in 2021 by a student resource center at Brandeis—references the same claim, linking the phrase to domestic violence. The Brandeis list (which, like the Stanford one, was removed from official university websites following backlash) includes a similar disclaimer that “no written record of this law exists today.” But it suggests, nevertheless, that speakers opt for “general rule,” over “rule of thumb.” The Stanford list favors both “general rule” and “standard rule.”

A sensitive speaker of English could consider removing the phrase “rule of thumb” from their vocabulary. The term has its roots in domestic violence: a British law stipulated that a man could beat his wife provided he used a switch no wider than his own thumb. This was the history referenced by The Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative in a list intended for use in Stanford University’s IT department, which made the rounds online just before Christmas last year. In a column helpfully labeled “Context,” the authors explained why “rule of thumb” should be nixed from readers’ usage. “Although no written record exists today,” the document reasoned, “this phrase is attributed to an old British law that allowed men to beat their wives with sticks no wider than their thumb.” A similar text—this one circulated in 2021 by a student resource center at Brandeis—references the same claim, linking the phrase to domestic violence. The Brandeis list (which, like the Stanford one, was removed from official university websites following backlash) includes a similar disclaimer that “no written record of this law exists today.” But it suggests, nevertheless, that speakers opt for “general rule,” over “rule of thumb.” The Stanford list favors both “general rule” and “standard rule.”

As the hedging about the lack of records hints, there is no evidence that the expression “rule of thumb” has its roots in spousal abuse. In fact, this claim has been consistently debunked by scholars for decades. It’s a folk etymology, and an incredibly persistent one at that, that arises with whack-a-mole insistence as fast as linguists and historians can challenge it.

“Rule of thumb” isn’t the only English idiom haunted by folk linguistic history. Nor is it the only case in which that false history is redolent of past (and present) atrocities: domestic violence, slavery, brutal class inequality. Around the same time the Stanford list came out...continue reading