On April 9, 2009, fourteen peace activists were arrested for trespassing onto Creech Air Force Base (AFB) in Indian Springs, Nevada. Following a week-long vigil critical of drones flown around the world from control trailers on the base, guards stopped the protesters as they attempted to cross into the military installations. Wary of the United States’ increased reliance on remotely piloted aircraft, both in and outside declared war zones, this act of civil disobedience aimed to disrupt public ambivalence toward remotely piloted aircraft. Reminiscent of anti-nuclear actions that occurred in nearby Mercury, Nevada, the arrested activists included anti-war protesters whose work spanned over 40 years of American military engagements. They kneeled just beyond the gated entrance, watched by three armed guards, while the base went on red alert.

Located forty-nine miles from Las Vegas, it took over an hour-and-a-half for the Las Vegas County sheriff’s department to arrive to arrest the trespassers. After some time, a drone appeared overhead, circling just above the base. The MQ-1 Predator looks awkward, in part, because of the bulbous head, which carries the system’s camera and sensors that can continuously collect information and relay it to computers via satellite. Powered by an engine also used in high-performance snowmobiles, the unmanned vehicle is driven by a pusher propeller, both of which distinguish the system from planes. Was the drone watching the protesters? What would be relayed to those inside the base? Would the protesters condemnations of unmanned war have been visible to the operators inside the control trailer? The drones circled a few times and were gone from the sky by the time the police arrived.

In Pakistan, drones are called bangana, a Pashto onomonopia variously translated as wasp or thunderclap. Over two-thousand people have been killed by these systems during the past five years. Bangana refers to the sound drones make and their humming might stand for their omnipresence above certain communities, as the aircrafts’ snowmobile engine emits an ongoing buzz. Unmanned systems often fly in groups, the multiple systems providing around the clock video surveillance in real-time. For their operators, consequently, drones exist in terms of sight, while, for those surveyed, they are known through their noise. The separation between what is seen and what is heard maps onto uneven geopolitical relations carried out, in part, through drone systems.

As far as the state is concerned, unmanned systems are an unquestioned ethical good, charged with both protecting the lives of American soldiers and pursuing terrorist threats. Republicans and Democrats alike support their development and the new forms of surveillance and targeting they enable. The sanguine view of drones sees the system as disconnected, focusing on the effects for the United States and its people, while ignoring how they are seen (and heard) by their intended and unintended targets. This was expressed in an exchange between an activist and a soldier entering Creech AFB. In a description of the activists’ vigil, Gene Stoltzfus wrote: “[A] man yesterday rolled down his window and shouted at me, ‘Do you have any idea how many American soldiers’ lives are saved every day by these aircraft?’ […] I remind[ed] him that the drone aircrafts create enormous hostility in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq that will take generations to overcome. He was not impressed.”

This brief conversation shows the limits of public debates about drones, precisely the conceptual gap that drones are designed to create. An encounter through a rolled down window stands in for an important political conversation that should examine the multiple concerns raised by unmanned systems. Similarly, in spite of the unprecedented connection which allows soldiers based in the United States to survey, track, and kill targets in countries on the other side of the planet, no exchange seems possible through the system. Shrouded in secrecy, especially in the case of drone attacks in Pakistan, the American public lacks knowledge about the drone warfare and the challenges to these strikes in the Middle East.

To support drone technology, the American government insists on the accuracy of unmanned systems and their role in protecting the country. Meanwhile, these accounts are widely contested both by international observers, as well as by people in the communities that are targeted. Yet, to focus on the accuracy of the strikes may overlook broader questions about the role of unmanned systems globally. What does it mean to rely on a system that negates the role of humans intimately involved in its operation to carry out killings on the other side of the planet? What forms of justice can be enacted through missile strikes from an unmanned vehicle? More than just killing innocent people, drones raise concerns about how politics is carried out and the role of humans in these processes.

The fourteen protesters arrested at Creech AFB were briefly jailed in Las Vegas before being released and charged with trespassing. At a local pizza joint later that evening, the waitress complained the vigil had turned bad, altering an otherwise ordinary day at Creech by putting it on high alert. The next day, trucks continued to rattle by on Highway 95 and the soldiers arrived without any interruption. Almost a year-and-a-half later, on September 14, 2010, the activists went on trial for their trespasses. In the courtroom, the prosecution explained how the protesters illegally crossed onto military property, while the defendants called on a range of experts to question the legality of American drone strikes. In this way, the trial paralleled the political and geographical disjuncture described above. In the end, the Creech 14 were convicted, although, they were credited for the time they served in jail and received no other penalty. The judge told them to “Go in Peace.”

***

Two recent artworks about unmanned systems also trespass drones, highlighting how the powerful modes of tracking and targeting associated with remotely piloted aircraft are also fraught with fallibility. Like the activists’ action, they question ambivalence to unmanned systems and serve to critique the ethics with which they are associated. 5000 Feet is the Best, a 2011 video by Omer Fast and the 2010 video, Drone Vision, by Trevor Paglen interrogate unmanned systems through systemic failures that connect technical flaws, human error, and political misjudgments. The artworks re-deploy images to highlight the limitations of what can be seen through drones and, correspondingly, the ways power is exercised through them, challenging the accuracy and objectivity the American government typically attributes to unmanned systems.

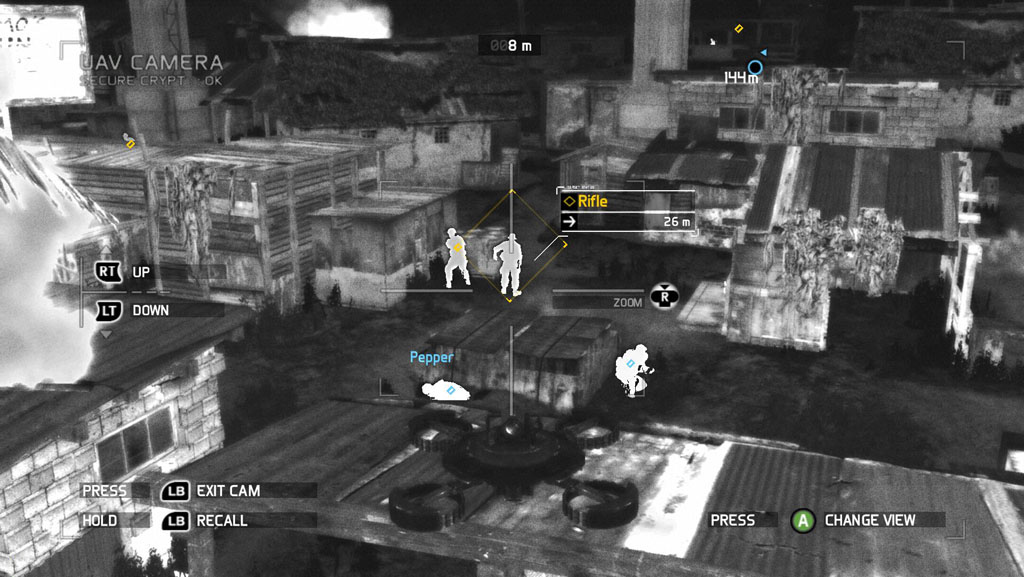

The title of Paglen’s piece, Drone Vision, at first seems to uphold the powerful view associated with remotely piloted planes. The sharp imagery suggests unmanned systems could be mechanical eyes that spy everywhere, providing close-up views of interiors and lingering on an official clock. But these images are transformed when one learns that Paglen acquired the video from an unsecured satellite data-link. Taken with the artwork’s silence, this gives the well-defined images of the video a layer of opacity, raising doubts about what can be known by sight alone. Iraqis were able to use similar tactics to watch images from American unmanned aerial systems. With software available on the Internet for $26 called SkyGrabber, insurgents were able to capture unsecured video transmissions sent from drone aircraft via satellite on their computers. This footage troubles the power the American government imagines is exercised through unmanned systems’ real-time surveillance, suggesting the video link might be more open than expected and, consequently, may extend beyond American control. Rather than trespassing across property lines, Drone Vision transgresses the hegemony the American government claims over unmanned systems and the information they collect.

Omer Fast’s video, 5000 Feet is the Best, is drawn from an account given by a drone operator with post-traumatic stress disorder, confronting questions about both who targets and who is targeted. At first, this is not apparent, though; rather, the video appears to be a staged interview between two characters, one who portrays a drone pilot and the other who acts the role of a journalist. The artwork's narrative moves back and forth between the operator’s story and the staged conversation, intertwining what is known and unknown.

The staged interviews occur in a hotel room, where a film crew is recording the conversation between the pilot and the journalist. The space is cramped and the drone pilot is uncomfortable. After abruptly leaving the interview, he walks into the hall and looks at the ceiling. The camera angle shifts to the texture of the ceiling paint and then the scene shifts to an aerial view of the desert, looking down from the sky. The video then cuts to the account given by the MQ-1 Predator operator. His face is blurred and the only distinguishable features are his eyes, contrasting with the sharp images found in the rest of the work. His narrative provides the voice-over for a series of aerial shots. As the images slowly move below the viewer, he recalls, “One time, I just watched a house for a month straight, for eleven hours a day.” But then, he also remembers moments of stress: “There are some horrible sides to working Predator. You see a lot of death […] doing this, you had to think there is so much loss of life that is a direct result of me.”

Death haunts the last staged interview. The pilot tells how “Mom, Dad, Johnny, and little Zoe are going on a trip.” A white, American family packs their things into a station wagon and leave, traveling to the countryside. On a lonely dirt road, they see a group of men in the distance and stop the car. The men are planting an improvised explosive device and the image cuts to the view from a drone. The family’s car drives slowly by the men and, at that moment, a Hellfire missile strikes, “almost vaporizing the men on impact.” The family emerges from the car like ghosts. With an American family in the target, the viewer is asked to question the view of drones that separates “us” from “them,” while the narration observes, “Seeing the world from above doesn’t just flatten things, it sharpens them, making relationships clearer.”

Drone war is about disassociating their people over there from our people over here, forming a wall between the watched and the watchers, those who are heard and those who aren’t. Simultaneously, though, the system transgresses borders, most obviously by targeting and killing outside declared war zones. Trespass, whether onto an air force base, into the drone control room, or into a drone's on-board memory, pokes holes in these barriers, crossing borders and making connections the drone program is designed to obliterate. While unmanned aircraft trace lines across space and perception, it is by infringing on these boundaries that we can find ways to more equitably draw connections, highlighting relations between ourselves and others, rather than upholding separations.