Secessionist petitions are not a rejection of, but a desperation for, an intimate union with the state.

At first glance, the neo-secessionist movement that has sprung up after the president’s reelection appears to fit neatly within the allegorical interpretive frame established by an image that went viral in the days following the November contest. Comparing the electoral cartography of 2012 with the geographic distribution of slavery in the antebellum U.S., establishing a continuity between slave states and red states, the image’s emphasis on historical repetition makes secession make sense. Armed with this antebellum allegory, liberal responses to the obligingly forthcoming petitions wrote themselves: neo-secessionists are the ugly inheritors of an ugly history, proponents of a racial and racist anti-democracy premised on a lack of faith in electoral mechanisms of participatory governance. But despite the substantive continuities between sectional crises in antebellum and contemporary U.S. political life, such critiques ignore a striking formal and generic difference between secessionism then and secessionism now. Whereas antebellum secessionists used state legislatures as their instruments of separation, today’s secessionists, strangely, have relied on petitioning the White House itself.

The right to petition sits in the First Amendment as an appendix does in a human body—benign but vestigial, the trace of a history that the Constitution itself helped render anachronistic. As legal scholar Gregory Mark writes, “Petitioning was a vital element in a political and constitutional culture that is not coming back.” The desuetude of petitioning seemed assured to Mark—he wrote this line in 1998—precisely because the vitality of petitioning depended on a particular cultural, institutional, and political matrix that is inoperative today. Petitioning once functioned as a mechanism by which varied subjects otherwise lacking access to political institutions could secure some kind of political being. It was thus a crucial instrument for those colonial polities under British imperial rule that, while only virtually represented in Parliament, nonetheless wanted to make demands on the state in a legibly legal form. Within the early post-independence republic, as well as within the broader Anglo-Atlantic world, petitioning would remain central to the political imaginations of non-franchised subjects of all kinds: women, free blacks, even slaves. Petitioning was also a primary tool for advocates of unpopular causes unlikely to be introduced for legislative consideration. Antislavery activists in the U.S., for instance, filled the House of Representatives with abolitionist petitions throughout the antebellum period. Indeed, the frequency of their petitioning led congressmen from the slave states, alongside northerners eager to maintain consensus and peace, to initiate a gag rule that prevented such petitions from being read or discussed.

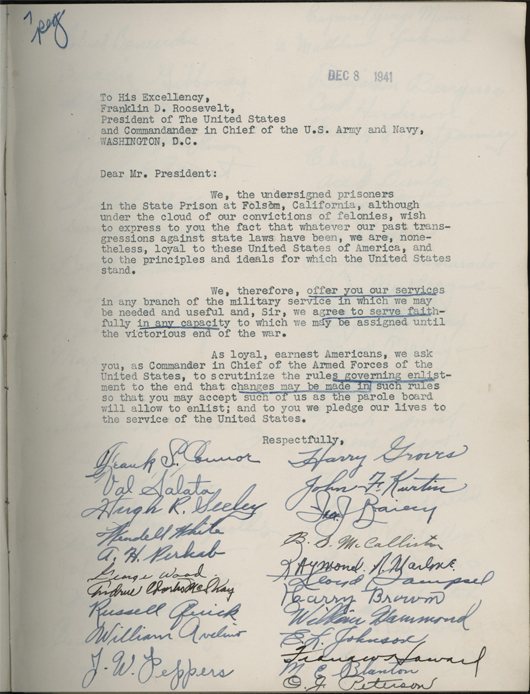

Petitioning has its roots in an imperial world in which opportunities for effective political speech were unevenly distributed throughout the polity. The very textual form of the petition derives from this unequal distribution of political power. Consider the “Olive Branch Petition,” sent by the Second Continental Congress in 1775 in the hopes of avoiding war with Britain. It begins: “Most Gracious Sovereign: We, your Majesty's faithful subjects of the Colonies […] entreat your Majesty's gracious attention to this our humble petition.” Note, first of all, the deferential tone. Whether the petitioners actually felt deferential is beside the point; the act of petitioning automatically positions petitioners as deferential. This condition of automatic deference obtains because petitioning assumes the non-sovereignty of the petitioner even as it posits the sovereign power and the potential effectiveness of the addressee. One does not petition impotent powers. Also note that the first request of the petition is about the text of the petition itself: before anything else, petitions petition for the careful attention of the sovereign. The petition conjures up an intimate scene in which a sovereign might generously recognize and respond to supplicants as political subjects worthy of attention and care.

It’s thus understandable why legal scholars tend to ignore the Petition Clause of the First Amendment and why we might think petitioning won’t (or can’t) come back as a viable political genre. Liberal mechanisms of parliamentary governance ensure the responsiveness of the sovereign to the citizen. Moreover, the generalization of voting rights has negated the non-egalitarian situation in which subjects lacked a sure means of accessing political life. The petition has fallen away to the extent that freedom has progressed, to the extent that the liberal-parliamentary state ensures the political subjecthood of all.

Despite this, the petition has returned. It has a new lease on life, and it lives this life in both right and left U.S. political cultures. The secession petitions are a dramatic example, but many who, say, participated in Occupy somehow ended up with an inbox filled with emails from Change.org. Corporatization has meant the potential addressees of our petitions have vastly expanded in number. We no longer limit our petitions to obvious sites of political power, such as the King, Parliament, the House of Representatives, or the President. We now approach other forms of corporate power as if sovereign, as if potentially responsive in the way that a sovereign might be. We live in a world where petitioning Wal-Mart seems not only reasonable but necessary.

This return of the petition marks something deeply troubled and troubling about the current structure of U.S. politics. Its return is in part a symptom of the proliferation of non-state quasi-sovereignties, and so indicates that massive accumulations of capital function as massive accumulations of political power. At the same time, the return of the petition demonstrates the felt bankruptcy of liberal modes of parliamentary governance. The impersonal anonymity of voting is no longer adequate for generating an intimate relation with the state; parliamentary modes of politics no longer feel political. And with good reason. If capitalism’s personifications have accumulated enough power to dictate that Republicans and Democrats alike embrace neoliberal doctrine and implement it in all branches of government (including the judiciary), what meaning, value, or even effect can participation in electoral politics have?

We come, then, to the secret meaning of the secessionist petitions: They evince not a rejection of, but a desperation for, an intimate union with the state. They solicit a relationship with the state in an era when neoliberal reforms mean that the presence of the state makes itself felt by vanishing—even if the petitioners themselves would consider their political desires aligned with an agenda of austerity. These petitions are so invested in the state that they grossly exaggerate its powers, deferentially ascribing a sovereign power to President Obama (a peaceful “grant”) that he obviously does not possess. I’m sure most of the signatories are well aware that there is no constitutional mechanism for dissolving the union, but realizing the petition’s explicit aim isn’t really the point. It does not matter if Obama responds positively or affirmatively to the substance of their demand. What matters is that he carefully read their words and caringly respond to them. What matters is that, however briefly, Obama’s eyes will have looked over their words, over their names, and taken time to think out a reply. What matters is that Obama will recognize them as political beings worthy of attention.

The very poverty of this desire indicates the depth of liberal-parliamentarianism’s crisis. Liberals have negotiated the crisis implicit in the aftermath of the 2012 election by ignoring it, by insisting that liberal-parliamentarian modes of governance work. The racists lost, after all, and the media assures us that the GOP will need to pursue, well, a less racist way of generating a voting bloc in the future. The rise of the petition, however, suggests that the capacity of the liberal-parliamentary state to grant subjects a meaningful political identity has become attenuated—if, indeed, it ever had that capacity. It suggests that neoliberalism’s peculiar articulation of governance and capitalism has decimated the diamond-shaped model of popular power distribution assumed by liberal parliamentarianism. The state—however austere—survives as an imaginative relation, as a projection of an impossible intimacy, as a fantasy that organizes the political lives of even those conservatives who fancy themselves some kind of libertarian anarchists. A truly anti-state politics would begin by unlearning our need for the state to care with the unfortunate knowledge that the liberal state will never be responsible to anything but the accumulation requirements of capital, that there’s no one to vote for, no one to petition.