It's a dog-eat-dog world down there at the South Pole

The morning of January 4, 1909 found Ernest Shackleton and his crew on the vast and desolate Ross Ice Shelf. Hell-bent on reaching the South Pole, they had faced some tough going. Fierce winds buffeted them. An ice chasm had swallowed their sole remaining pony, and the lost animal's burden thus became theirs. Each crew member pulled a sledge loaded with some 70 pounds of supplies, straining muscles left cramped by nights spent in ice-rimed sleeping bags.

Yet frostbite and charley horses pained them less than the hunger they felt. Their rations nearly exhausted, they knew starvation loomed. "The end is in sight," Shackleton wrote that bleak January morning. "Short food and a blizzard wind from the south." In four months they had enjoyed only one full meal. They subsisted on crushed biscuits, rancid pony meat, pemmican (meat mixed with vegetable matter and fat), the occasional seal or penguin -- and these in portions barely able to sustain them. How long they might continue to sustain them, no one could say. In much the same state a month later, Shackleton would write, "Feel starving for food.... Talk of it all day."

If ever a place existed where it was better that food be had than talked about, it is Antarctica. The continent boasts no forests, pastures, prairies, or rivers. Its frigid wastes cover an area larger than India and China combined. It is quite literally like no other place on earth. To find its nearest equivalent, you have to look to outer space -- to Europa, the icy moon that orbits Jupiter, to be exact.

For a place so utterly blank, Antarctica has made for many inked pages. Each year sees books published on any number of Antarctic-related topics. Two recent releases, Jason C. Anthony's Hoosh: Roast Penguin, Scurvy Day, and Other Stories of Antarctic Cuisine,

and Wendy Trusler and Carol Devine's The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning, take up the subject of hospitality in an inhospitable land, which owed as much to luck as to invention or proper planning. What comprises "Antarctic culinary history," Anthony writes, is "a mere century of stories of isolated, insulated people eating either prepackaged expedition food or butchered sea life."It helped if some of these isolated, insulated people knew their way around the kitchen. "The cook, however good or bad, is an artist whose simple vocation is to make others lives happier," observed chef Raymond Oliver. More magician than artist, a cook with an Antarctic expedition ranked as one of its most important members. His kitchen little more than a Primus stove, his ingredients either canned or scrounged, he conjured nourishing dishes as if from the gelid air.

The annals of Antarctic exploration abound with colorful depictions of beloved cooks. Rozo, the popular cook of Jean-Baptiste Charcot's 1903 French Antarctic Expedition, offers a fine example. An air of mystery surrounded him. No one knew his true name or age because he fraternized little, preferring the company of Toby, the expedition's pet pig, to that of his fellow crew. He read widely and had a quick wit. Yet he hated to wear socks and would instead pad about in old house shoes that he slipped over his bare feet. The moist croissants and sweet patisseries Rozo whipped up, however, more than made up for any eccentricities. Indeed, his quirks and culinary skills combined to make him seem larger than life. "He was like someone from a novel," Charcot recalled, "and we almost expected him to arrive one day and announce ... that he knew a very easy way to the Pole itself."

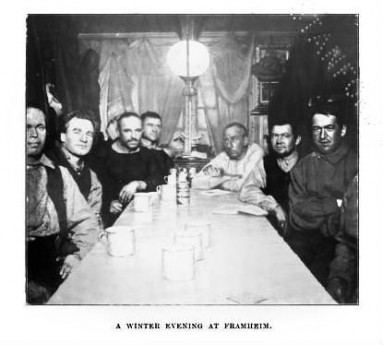

But Rozo knew no way, easy or hard, and the French expedition penetrated no further than the Antarctic coast. The Norwegians were the first to reach the South Pole in 1911. Led by Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian expedition featured its own treasured cook, a man by the name of Adolf Lindstrøm. From his tiny hut standing at the foot of the Ross Ice Shelf issued savory seal stew and stacks of buckwheat pancakes slathered in cloudberries. Lindstrøm took care to cook in such a way as to preserve as much of the food's nutritional value as possible. "A better man has never set foot inside the polar regions," wrote Amundsen in praise of Lindstrøm. "He has done Norwegian polar expeditions greater and more valuable service than anyone else."

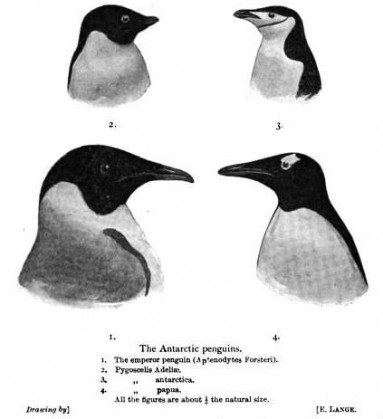

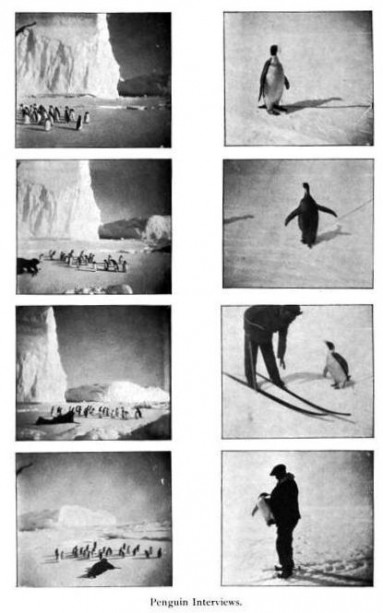

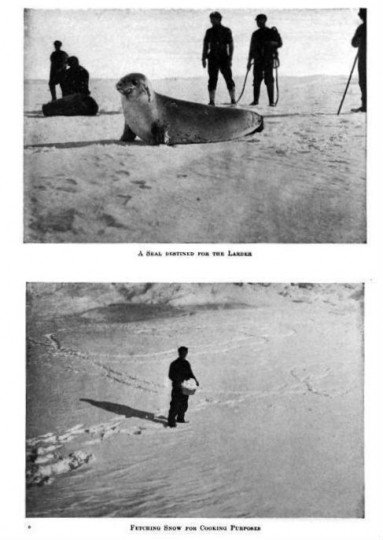

Any cook worth his salt knew how to transform the Antarctic's seemingly unappetizing wildlife into palatable fare. A dish of penguin prepared for the American explorer Frederick Cook tasted to him like "a piece of beef, odoriferous cod fish, and a canvas-backed duck roasted together in a pot, with blood and cod-liver oil for sauce." The Germans fared a bit better. Karl Klück, cook for a 1901 expedition, reliably whipped up seal sauerbraten tasty enough to please any bürgermeister.

T.C. Clissold, cook for Robert Falcon Scott's 1910 British expedition, brought seal meat within kissing distance of haute cuisine. His seal rissoles sent the crew into raptures, and his seal galantine, with its force-meat stuffing and cold aspic glaze, left a sheen of gourmandise on the stiffest upper lip. "It is the first time I have tasted seal without being aware of its particular flavor," Scott wrote of tasting Clissold's handiwork.

Of course, such brave dishes as those by Klück and Clissold represented Antarctic cuisine prepared under the best circumstances. Once the explorers took to their sleds, rissoles and sauerbraten became mere memories and austerity the rule. They dined on whatever they managed to forage from snow drifts or whatever provisions they brought along -- their ponies and sled dogs included. The practice of eating pack animals, while seemingly cruel, was driven by a compelling logic: As the explorers consumed food and fuel, their sled loads lightened. Lighter sleds needed fewer dogs to pull them. Dogs thus made redundant became food for their fellows and the explorers. Amundsen slaughtered 24 healthy dogs during a single expedition. Doing so filled him with a sublime awe. "Great masses of beautiful fresh, red meat," he wrote of the butchering, "with quantities of the most tempting fat, lay spread over the snow," calling to mind "memories of dishes on which the cutlets were elegantly arranged side by side, with paper frills on the bones, and a neat pile of petit pois in the middle."

When not eating their sled dogs and ponies, explorers ate hoosh. Otherwise known as "meat stew of the ravenous," Anthony writes, "hoosh is a porridge or stew of pemmican and water, often thickened with crushed biscuit." But anything, really, might get tossed in the pot -- seaweed to bulk it up or, if Fortune smiled, brains, livers, and kidneys of various Antarctic animals to boost its nutritional value. Anthony notes one rather exotic hoosh made of penguin flipper and rope treated with Stockholm tar.

However bizarre or nasty its ingredients, hoosh enjoyed enduring appeal. Hungry explorers coveted it, and anyone who cheated them of their share had hell to pay. Expedition leaders consequently devised various stratagems to divvy the stuff. Scott, for instance, resorted to playing "Shut-Eye," in which he would assign, without looking, mugs of hoosh to men who themselves had their backs turned.

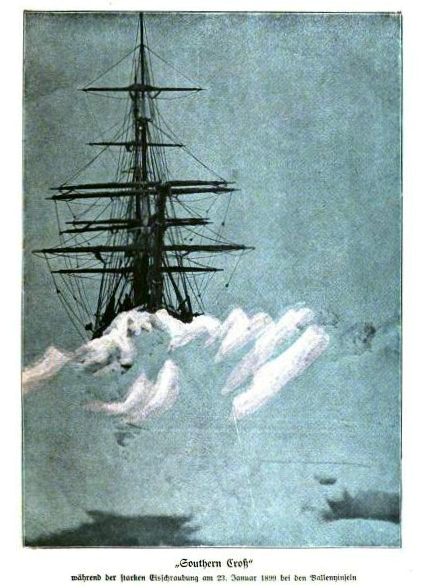

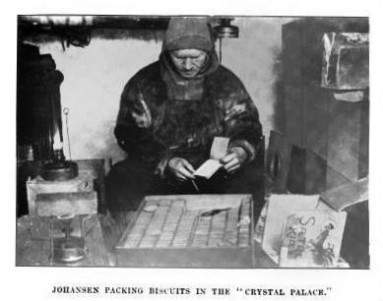

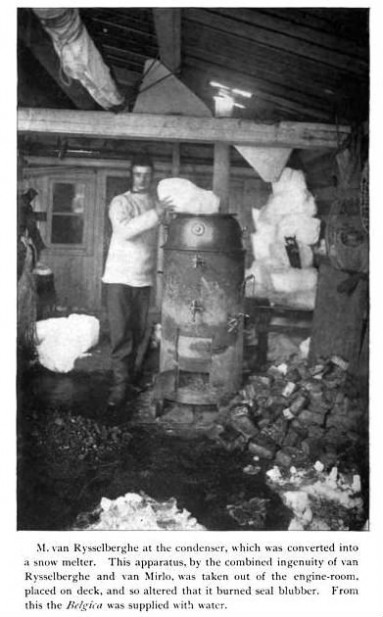

Hoosh was prized so highly because in most cases other options were worse. A diet unsupplemented by Antarctic bushmeat led to scurvy. The fate of the 1897 Belgian Belgica expedition attests to the ravages of this disease born of malnutrition. That ship’s crew planned their polar foray with the expectation that before winter’s onset they would head north. They failed to beat a brisk enough retreat, however, and found themselves locked in ice. Fresh food nowhere available, the men of the Belgica improvised, Anthony quotes one of the crew members as saying, with "laboratory mixes in cans ... hashes under various catchy names ... sausage stuffs in deceptive forms, meat and fishballs said to contain cream, mysterious soups, and all the latest inventions in condensed foods." None of these marvels of modern food processing contained enough ascorbic acid to prevent scurvy. Two sailors went insane, the rest endured bleeding gums, blackened legs, stubborn wounds, and other unpleasant symptoms. Even the ship's cat died.

Worse than scurvy was starvation, as Shackleton's men discovered that cruel winter of 1909. "The group's thin hooshes ... could not compensate for the thousands of calories burned daily while hauling their heavy sledge," Anthony writes. A man pulling a sledge burned more calories a day than does one pedaling a bicycle in the Tour de France. And though the explorers organized their treks along "an umbilical cord of depots," much could go wrong. The worst period of the expedition saw them reduced to four "miserably thin" biscuits per day.

When hunger pinched, Shackleton and his men joked about food. When hunger gnawed, food became no laughing matter. It became, rather, stuff to fill the head if not the belly. "On the march," Anthony continues, "they described previous feasts and fantasized about the banquets they would lay out for each other if they reached civilization." One such fantasy involved six sumptuous meals served in a single day.

When Shackleton's men didn't dream of food, they read about it. More treasured than bibles were penny cookbooks they brought along on the trip. They studied the recipes therein, annotated them, and argued over which ingredients worked best and which manner of preparation produced the tastiest outcome.

As sails ceded to steam, polar expeditions became much less of a gamble. And, as the risks decreased, so too did the savor of the adventure. The history of Antarctic food "loses some of its drama after the heroic age," Anthony admits. "[T]oo wealthy and too well-informed," mid 20th-century explorers traveled on self-propelled ships and sleds and ate nutrient-dense, industrially produced rations. Yet Wendy Trusler and Carol Devine would likely dispute this conclusion. The many anecdotes and accounts they include in The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning suggest that, in terms of diet or anything else, modern-day polar forays aren’t necessarily duller than those of yesteryear.

In 1996, Canadians Trusler and Devine journeyed with several groups of volunteers to a small island 120 kilometers off the Antarctic coast to cleanse it of 28 years’ worth of accumulated garbage. Hence the book’s title. The book itself may be variously describe as a cookbook, a diary, a photo-journal, and tribute to those early explorers who survived on penguin and dog-paw stew.

Devine tells an inspiring story. "I wanted to do something previously untried," she writes of organizing the expedition. Together with a company that "took adventurers to the Antarctic," she established the Volunteer International Environment Work foundation and lead a trip to clean out debris and scientific equipment at the Henryk Arctowski station in the South Shetland Islands. Not long after, she set up a second expedition, Project Antarctica II. Larger than the first, this project was plagued by provisioning fiascoes, cultural misunderstandings, logistical difficulties, and rotten weather. "We knew what we'd face couldn't be anything as serious or tough as the challenges endured by old-school Antarctic explorers," Devine writes, "but despite understanding scurvy and having the benefit of modern communication, technology and flights to the Antarctic, the variables were many."

One constant among the variables was Wendy Trusler, whom Devine hired to be the expedition's cook. As ingenious and stalwart as her Antarctic forebears, Trusler recounts the joys and hardships of kitchen management at the end of the earth. "Pizza night Custard with rum sauce and candied almonds Cooking hell," reads a December 23, 1995 entry from Trusler’s diary reproduced in the book. "Will I get organized?" The answer was decidedly "yes," because two days later she pulled off a dinner of turkey with dressing, roast daikon radish, yams and onions, cranberry sauce, corn on the cob, asparagus with dill butter, green salad with croutons, and, what must have been a divine treat in the polar wastes, a Bavarian apple torte. "The best Christmas ever," she judged the occasion. Given what she was up against, the reader is inclined to agree.

Her skills honed in the "bush camps across Canada," Trusler subscribes to the school of "pitch-and-toss cookery," in which scarce ingredients force instinct and imagination to commingle in a sort of culinary gestalt. She takes the same approach to the recipes in The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning. "You'll find these recipes are written in an idiosyncratic style," she writes, "but I hope they'll encourage you to taste, look for visual clues and develop a real feel for whatever you are preparing."

Trusler's recipes are a charming mix of her own idiosyncratic concoctions and recipes cherished and shared by her fellow activists. There's "Maxim's Moonshine," a potent liquor of yeast, sugar, and water. Trusler got the recipe from a Russian glaciologist who warned that "it is ... absolutely disgusting stuff, which may be consumed at an Antarctic station when nothing else is available." Maxim also supplied an equally dubious recipe for a mixture of kelp, onion, garlic, and mayonnaise he called sea cabbage salad. Trusler juxtaposes these concoctions with more appetizing offerings such as mulled wine, rosemary maple borscht, rosemary-encrusted lamb ribs, custard with fruit compote, cranberry fool, and cheese fondue. (This last dish moved one volunteer to opine, "If Wendy had been along, Scott would have made it.") Containing some the most tempting expedition cuisine I've seen, The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning is a must-buy for eco-conscious foodies.

Devine writes that Trusler's cooking "reflected doing the best with what you have." Her sentiment chimes with the notion, first advanced by French theorist Roland Barthes, that, more than anything else, food "constitutes an information." Contained in that information is "an entire 'world,'" by which he means "social environment." The biggest pot of hoosh couldn't match a tin of peaches when it came to comfort and reassurance. Shackleton understood this. He famously squirreled away jam, chocolate, anchovies, and other treats to give his men whenever he sensed their spirits sink. When Trusler radioed for brown sugar and chocolate chips from one of her supply ships, surely she wanted to recreate a social environment homely and familiar. "[I]t's funny what you can't live without," she observes.

Both Anthony's Hoosh and Devine and Trusler's The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning illustrate the extent to which food nourishes the spirit as well as the body. Anthony's freewheeling account is sometimes difficult to follow. But the chapters detailing the trials and tribulations of the cooks of the heroic age of polar exploration are engaging, and Anthony has collected an impressive amount of information on the topic. This alone makes his book essential for anyone interested in exploration cuisine. The Antarctic Book of Cooking and Cleaning is an enjoyable glimpse into a noble endeavor undertaken in the closing years of the last century, when there still were places that seemed cut off from the rest of the world.

Today the Antarctic stations have Internet access, a development that has undoubtedly made any sense of isolation less than utter. And climate change has spurred a new spirit of exploration, one more dubious than heroic. Various governments and private interests have begun to consider plundering these white wastes for the gold, uranium, natural gas, and oil that lies deep beneath them. If that happens, Antarctica, remote and vast as it is, will surely go to the dogs, leaving none even to eat.