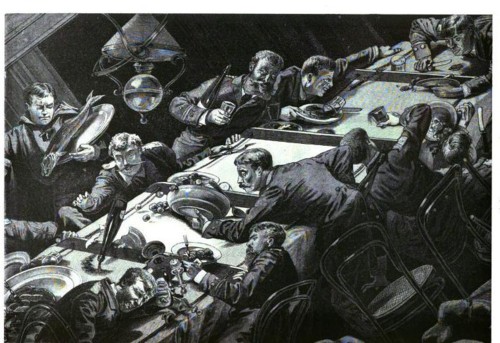

Dinner on a Man-of-War, Anonymous, ca. 1893

Baron Thomas Babington Macaulay’s sharp, scintillating 1856 biography of British author Samuel Johnson turned out to be quite a labor of love. Macaulay dedicated the last six years of his life to completing it, and even his editor, Mr. Adam Black, couldn’t convince him to accept payment after its publication, even though it proved immensely popular with readers and critics alike.

Macaulay’s Life of Samuel Johnson owes its popularity in part to its author’s apt deployment of unusual details and peculiar metaphors. Readers learn that “Johnson dressed like a scarecrow and ate like a cormorant,” and that Johnson’s biographer, lawyer and diarist James Boswell, had a mind that “resembled those creepers which the botanists call parasites.” Together these imaginative and fantastic descriptions make for a book that charms in its presentation of one of Britain’s most fascinating literary figures.

One of Macaulay’s more colorful descriptions touches on Dr. Johnson’s insatiable appetite for rotten meat and expired dairy. “Even to the end of his life, and even at the tables of the great,” Macaulay writes

the sight of food affected him as it affects wild beasts and birds of prey. His taste in cookery, formed in subterranean ordinaries and alamode beefshops, was far from delicate. Whenever he was so fortunate as to have near him a hare that had been kept too long, or a meat pie made with rancid butter, he gorged himself with such violence that his veins swelled, and the moisture broke out on his forehead.

Spoiled hare and rancid butter are certainly acquired tastes, but the old Latin maxim teaches us that you can’t debate such things, especially when your disputant has the tastes and “anfractuosities” of Dr. Johnson, qualities which, as Macaulay writes at the end of his book, “[serve] only to strengthen our conviction that he was both a great and good man.”

____

The Austerity Kitchen, like Walter Benjamin’s chronicler, hews to the principle that she ‘who recounts events without distinguishing between the great and small, thereby accounts for the truth, that nothing which has ever happened is to be given as lost to history.’ The Austerity Kitchen applies this principle to matters culinary and gustatory in the interest of bringing to life the context, aesthetics, and practices of our cultural heritage past and present.