“A color which would be ‘dirty’ if it were the color of a wall, needn’t be so in a painting … There is no criterion by which to recognize what a color is, except that it is one of our colors.” —Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on Color, 1951

The first time I walked into Erik den Breejen’s studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn, I didn’t know what to look at. As with many artists’ studio spaces, there’s a precarious mix of order and disorder: canvases (blank and full) leaning up against the walls, books, LPs, coffee cups, ashtrays. The sense of domesticity, intimacy, and industry are palpable.

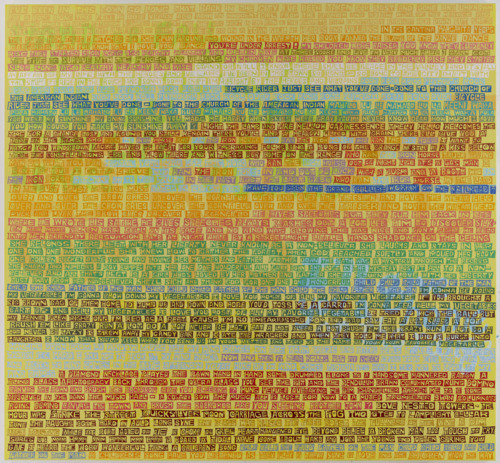

What caught my attention was a large painting hanging on the wall, seven-by-nine feet, a blue and grayish hologram that from the doorway looked like part of the wall. Facing the painting, it became clear: These were blocks of words and letters, all familiar to me, as I slowly began to decipher them:

If you should go skating on the thin ice of modern life…

Mama loves her baby …

It was only fantasy…

VERA! VERA! What has become of you…

I had known for weeks that den Breejen had been at work on a piece related to Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Nonetheless, its canvas manifestation took me by surprise. Directly facing the wall of words, I felt at once, Yes, this is how the album looks. “One of the things that occurs to me when I make a painting of all the lyrics of an entire album, is that I can see the whole album at once,” he says. “You can never hear an album all at once, which can be frustrating. It can lead one to listen to an album over and over again, whereas an object can be taken in all at once.”

Pop music is a source of inspiration for den Breejen that is both primal and spiritual, though his relationship to the music he works from is ambiguous at times. Den Breejen, a musician in his own right (currently the lead singer of Big Game), uses musical experience as the subject of much of his painting, but the lyrics are the only element he appropriates. The colors, shapes, textures, and size are completely his own.

Born in Berkeley, California, in 1976 to a painter and legal indexer, den Breejen studied fine arts at UC Santa Cruz and California College of the Arts before leaving for New York in late 2000. New York City was decidedly different 11 years ago, den Breejen says: “There was still something unexpected and unpredictable. Maybe it’s because I was young, but it wasn’t as privileged or as safe or sterile or bratty or obnoxious.” An oscillation between feeling trapped and indebted to the city keeps him there, as does the development of his work.

Even then, den Breejen drew on the experience of music fandom in his work. “It was still very much the Magnetic Fields’ 69 Love Songs era for me. I told a roommate that I wanted to make stickers that said ‘Listen to the Magnetic Fields’ and stick them around where [Magnetic Fields’ Stephen Merritt] lived. My roommate was sort of perturbed that I would want to expend creative energy honoring someone else’s work, instead of making my own.”

As a precursor to The Wall painting, den Breejen performed a recital in a small gallery of all the lyrics to the double album. “I kind of wish I’d worn a suit or looked professorial. It may have been a bit too casual. I liked to clarify at the time that I hadn’t memorized the lyrics but that I simply knew them, which is true.”

Such intensity of fandom has since found more direct outlet in den Breejen’s paintings. Only because den Breejen has internalized the music so thoroughly can he re-express it visually. The beauty of popular music, in its very ubiquity, is that it doesn’t belong to anyone, but rather to everyone. There’s more space and sympathy for interpretations in different mediums. A cover of a loved song can often seem banal if it’s not transformative, but den Breejen adds to the work by painting it rather than merely covering it.

His newest show, Smile, which opened December 10 at the Chelsea gallery Freight + Volume in New York, is a more ambitious invocation of his previous approach: more than 10 paintings that honor and decimate the lyrics of Brian Wilson’s ill-fated SMiLE album, a solo project of sorts complicated by decades of strife, delay, and painstaking attention. Den Breejen’s Smile is inspired by the original 1966-67 Beach Boys recordings, long bootlegged and recently released by Capitol in two-disc and nine-disc editions after many tracks had trickled out over the years.

Den Breejen’s new paintings are a combination of old and new techniques of his, based on a loose system of changing color as the music changes and creating word blocks that create an image. As with The Wall painting, they begin with the ritual of language. The result is painting that is very literary; in its appropriation, it changes tiers. “I’m not consciously nostalgic, but I am aware that I am more involved with music from the past than the present,” den Breejen says. “Maybe I have fallen into a time warp from listening to too much ‘60s music for too long. It’s like these guys are my friends or something. Seriously, I guess it might have affected my brain listening to Beach Boys records every day for a year and not much else.”

His attunement to the collaborative process suggests why he would be attracted to an artist like Brian Wilson and to SMiLE, an album that allegedly drove the Beach Boys apart, drove Brian Wilson himself insane, and ultimately required the subsequent recruitment of passionate admirers of the unfinished masters to be completed: “Does a building lose authenticity because the architect did not build the entire thing alone?” den Breejen asks. “Should every builder who worked on it be credited? There persists a very attractive romantic myth about the lone artist, the suffering artist. Why should an artist have to create alone? Because they sign their name to it?”

Wilson embarked on SMiLE with the intention of beating the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to the punch, and the album’s eventual shelving and delay is the stuff of legend. Wilson wanted to create a “teenage symphony to God” but the result is more a symphony to America’s adolescence. “Good Vibrations,” the song that encapsulated the direction Wilson hoped to go with SMiLE, “is brilliant because it is accessible and difficult at the same,” den Breejen explains.

With SMiLE, Wilson was developing a form of “modular music” similar to that of musique concrete, one of the foundations of electronic music. “Wilson would record endless pieces of music and edit and re-edit them until he got what he wanted. It was a very unusual way to work at the time,” den Breejen explains. Wilson’s work with lyricist Van Dyke Parks also lent the album some its arcane, dark, and mysterious wordplay, an antidote perhaps to Wilson’s “cartoon consciousness,” as Parks has described it.

The most overwhelming aspect of den Breejen’s work is the color — there’s something assaulting, almost abrasive about it. You don’t know what to do or say in face of such exuberance — so maybe laughter is appropriate. Yet den Breejen’s enthusiasm is also there. It is one thing to be naturally enthusiastic; it’s another to allow it to come across in paint. Den Breejen describes an “element of synesthesia” in his work — the conflation of the senses. One sees color when hearing music or thinks of different words as having volume. “One of my aims is that the formal qualities of the paint — color, surface, shapes — would act as a stand-in for the music, and you would still have the words, except this time instead of words melded with sound, they are melded with image and shape. I don’t know how effective it is. That’s kind of what art is in some ways — ongoing research.”

Like the Beach Boys, den Breejen comes from California, but his work harbors little nostalgia toward ’60s-era California as a sublime promised land. Just like the lyrics of the songs, the California depicted in Wilson’s music seems more than ever a place of the mind. Wilson’s “cartoon consciousness” is confronted in den Breejen’s complicated color pieces, a painting antidote that reveals some of the preternaturally darker corners of the most cheerful demeanor, like a biofeedback scan. “It can drive one a bit crazy,” den Breejen says about immersing oneself in the Wilson Smile world for too long. He extends this to even more confessional examples of pop music’s ability to ruin: “I think that confessional, personal songwriting acts as a kind of therapy or some bizarre transcendent identification.