The distance between Juzo Itami's Tampopo and David Chang's Lucky Peach shows how far American food culture has come since the movie was first released

When Roger Ebert first reviewed the film Tampopo, perhaps still the only “Ramen Western” since its American release in 1987, he saw the unfamiliar flavors of its obsessions in a favorable light. A collection of vignettes about the food in Japanese life, the movie takes its name from its central story about a charming woman named Tampopo

Ebert was right to relate the film to more blue-collar tastes, as the obsessive food culture Tampopo both mocks and exalts is far more democratic than the American take on Japanese food in the last years of Regan.

These unique, nuanced relationships each of Itami’s characters have with food save Tampopo from looking like a black-or-white dichotomy, two poles of hedonistic have-not desire and palate-deadened bourgeoisie. Food is cast as emotional, sexual, and intellectual, something to savor, lust after and debate. I was a vegetarian when I first watched it, so the movie didn’t have the predictable effect of making me crave a bowl of meaty tonkotsu, pork-bone broth cooked to milkiness—I wanted to consume Tampopo’s food culture whole. In recent years, something more akin to that culture has developed in America. The profusion of ramen connoisseurs has dislodged instant noodles from the status quo, yes, but the obsessive drive to cook or eat excellent noodle soup has implications that go beyond simple consumption. Chefs and diners are now hungrily engaging in a hierarchy of influence that functions like that found in art or film or music, and the increasingly intellectual nature of that relationship is changing both the way we eat, and food’s place in our understanding of culture.

The paper of record

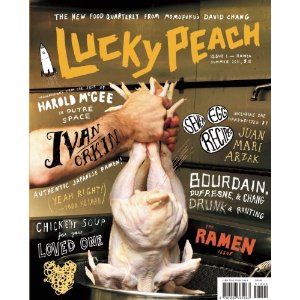

for the noodle-shop-hopping, food-porn-Instagraming slice of the population is undoubtedly Lucky Peach, the quarterly “journal of food and writing” edited by Momofuku chef David Chang and published by Dave Eggers’ literary outfit, McSweeny’s. The first issue, released in the summer of 2011, was entirely devoted to ramen, its pages filled with a plurality of voices: those of chefs, scientists and novelists exploring the various elements that make up the platonic bowl of Japanese noodle soup. In his introduction to the second issue, editor Peter Meehan aptly describes the debut as “the magazine equivalent of throwing an m-80 into a bowl of ramen and taking a crime-scene photo of the results.”The journal takes its name from Chang’s restaurants. Momofuku is Japanese for “lucky peach,” but before Chang began to link together his empire with those four syllables, the name was most strongly associated with Ando Momofuku, the inventor of instant ramen, who is profiled in the first issue. So even if Lucky Peach has put ramen behind it as an overt theme, the publication is always operating under the influence of noodles. In subsequent issues, which have focused on themes like “the sweet spot”, the relationships and differences between chefs and cooks, the food culture of America, and Chinatowns, there are still echoes of Tampopo in both theme and structure. Both magazine and film are tangles of narrative, the disparate voices ultimately adhering in order to describe, in detail, the particulars of food culture. But why?

Anthony Bourdain, Lucky Peach’s resident movie critic, writes about ramen on film in the first issue. The column starts off with Bourdain recounting the basics of Chang’s biography: “After becoming disenchanted with work in the financial-services sector, Chang traveled to Japan to teach English and study the art of Ramen.” Bourdain seems to find the record too dull, so he tosses it aside and instead fabricates a new narrative in which “Chang fell under the influence of Juzo Itami’s maniacally fetishistic ode to ramen, Tampopo.” This kind of mythologizing, and Chang’s omniscient presence throughout the pages of Lucky Peach, make the chef into something quite different than an editor; he functions more like the magazine’s semi-fictional protagonist, and, in a larger sense, a cumulative symbol tasked with representing the entire food culture he has had some hand in creating. It could be tempting to call Lucky Peach a vanity publication, especially in the face of Bourdain’s weak fantasies of Tampopo’s influence, but the fact that Chang maintains something of an everyman air makes his presence in the magazine more like Tampopo’s in the film—the reader is rooting for him.

Tampopo opens with Goro and Gun, a salt-of-the-earth trucker in a cowboy hat and his goofy, neckerchief-wearing sidekick,

From left: Goro (Tsutomu Yamazaki) and Gun (a young Ken Watanabe)

From left: Goro (Tsutomu Yamazaki) and Gun (a young Ken Watanabe)“What it is, Mr. Bourdain hopes, is a new type of cooking show, a kind of intellectual biography,” pronounces The New York Times about his new PBS show, The Mind of a Chef, based on footage shot for the shelved Lucky Peach iPad app. As such, attribution is an idea that’s mulled over on many a page of Lucky Peach. The important developments in ramen are carefully mapped out in terms of time, place and innovator. Tsukemen, a dish of cold noodles that are dipped into an aggressively seasoned, concentrated ramen broth, was invented in the 1950s by Kazuo Yamagishi. The double-soup style of ramen, in which the distinct elements of the broth are prepared separately and then combined in exacting proportions to make each serving, was developed at the restaurant Aoba around 2000. Bourdain summed up the relationship between this historical approach to understanding influence and the creation of new ideas for the Times, claiming he’s

exploring the creative process, the anatomy of a style of cooking. Not just what inspired this dish, but where did it come from, what are they thinking about, what’s intriguing to them. How did we get here? The end result is often the end of a long story and from early on we’ve been looking at Chang’s food as part of a long and very interesting story.

In other words, the obsession with influence is wrapped up in a desire to create new dishes along with new narratives, the characters of food and chef imbued with a rich backstory.

The attribution theme is carried on in Issue 3, the chefs-and-cooks volume, where an entire article maps the spread of the molten chocolate cake. Rachel Khong charts its drift from Michel Bras’ restaurant in Laguiole, France, where a single-serving cake with a liquid gânache center was first served in 1981, to Disney World, then to the freezer isle of every chain grocery store. Bras’ gargouille, a much-aped salad of countless vegetables served in edible “soil,” and the many techniques Ferran Adría developed at El Bullí are noted for their outsized influence and both attributed and unattributed mimics. Bras’ innovations are approaching their thirtieth anniversaries, and Adría first envisioned sauces whipped full of air instead of leaded with cream and butter in the 1994. Yet to many American palates this kind of cooking is still new and novel; even to those familiar with it, it still scans as modern. The trickle-down of influence is as old as codified cuisine, but the rate of the drip is picking up. With ideas moving from kitchen to kitchen more rapidly, attentive diners are becoming increasingly literate in reading a dish’s influences.

Such interpretation of influences falls to food bloggers nowadays, and the fact that the online dialogue doesn’t require purchasing $20 appetizers has broadened the audience of high-minded dining in an odd and, at its best, intellectual manner—one that involves reading dishes rather than eating them. It’s now possible to have a relatively informed opinion about such wallet-denting restaurants as The French Laundry or Alinéa, for example, without having dined there. We judge food we’ve only watched being cooked on television, and menus and photo of dishes are analyzed like literature or works of art. In the eyes of an obsessive diner, a dish at the inventive hipster joint with pickled rosehips is as obviously indebted to René Redzepi’s Noma as any art school kid’s splattered canvas is to Jackson Pollack.

Having an intellectual understanding of culinary influences makes for a different dining experience, especially in the case of less well-off diners, for whom actually tasting the cooking of Keller or Chang or Redzepi would be a significant occasion. This can be seen in a vignette in Tampopo showing an office underling attending a business luncheon with a group of executive suits. Sole meunière, consommé and Heineken is the bland menu selected by the entire table—save our young assistant, who, rather than defer to the choices of superiors, pours over the menu like a book, asking astute questions of the waiter—Boudin-style quenelles? Doesn’t Taillevent serve the same dish? The waiter explains that the restaurant’s chef had previously worked at the famed Parisian restaurant, and had brought that novel preparation back to Tokyo. While it’s clear that the businessmen at the table will be picking up the bill, our more knowledgeable diner is able to engage with the narrative of the restaurant, of the chef, in a more intimate manner than the suits’ transactional, economic relationship—and that’s apparent both in the more personal interaction the ingénue has with the waiter and in his enjoyment of the meal. In the homeless encampment scene we see a similar approach of augmenting experience with knowledge: the vagabonds rattle off the best recent vintages of Bordeaux, opining on the ways in which weather affected harvests, on which appellations are home to the best vines—all of which is prelude to sipping the 5-centimeters of left-bank Boudreaux decanted from the dregs of a tossed bottle.

But despite its growing size, pace, and increased media coverage, today’s culinary influence chain remains thoroughly dominated by men—just as Tampopo’s cabal of ramen advisers is all male, just as that table full of Sole meunière and one order of pastry-wrapped escargot is surrounded by men. Tampopo, a single mother and business owner, is something of a feminist character, even with Goro, the old ramen scholar known as The Master, and others whispering soupy secrets in her ear. The dying mother from another brief vignette is far more subject to the patriarchy. She rises from her deathbed when her distraught husband commands her to cook dinner. Having obediently served her last supper, she slumps to her death without even tasting it.

A consistent feature in each Lucky Peach issue so far is a multipage transcript of wandering conversations between Chang and a few other male chefs about food and cooking and restaurants. There’s plenty of swearing and the occasional dude-that-makes-you-sound-gay joke; just chef-bros being chef-bros. All this talk about influence and ideas between men never drifts into any Harold Bloom-like argument about weak chefs and strong chefs—but it comes close.

Thankfully, there are women’s voices present in Lucky Peach too, including Christina Tosi’s, the pastry chef at Chang’s Milk Bar, and Christine Muhlke’s, the Executive Editor of Bon Appétit, who is the strongest dissenter in Chang’s sometimes imperfect democracy. She writes in issue 3 about the ways in which ideas trickle down through the ranks in both fashion and food industries, describing the sharing of ideas between the likes of Chang and his colleagues as “the echo chamber/circle jerk of chefs.” In her less romantic description of the trickledown, “sharing all of their big ideas at conferences” and eating at one another’s restaurants is just a precursor to the moment when “they get drunk together in man-groups and say mean shit about whoever isn’t there before going off to puke up oyster globules.”

It appears that humans were capable of discerning that they wanted the sweet and savory more than the potentially poisonous or rotted foods that tasted bitter and sour before we learned to pursue the pleasurable over the painful in other aspects of life. John Allman, a Caltech neuroscientist who studies the insular cortex, is quoted in “The (Neurobiological) Sweet Spot,” an essay in issue 2, saying that our ability to handle the emotions of life beyond taste “evolved out of neural circuitry that gave us the ability to make food-related decisions.” The outsized attention Lucky Peach dedicated to umami is no refined flight from base sustenance, but intimately related to our very humanity.

Itami makes a similar thesis in the final frames of Tampopo, which takes the form of a lingering shot of a mother sitting on a park bench, breast-feeding her infant child. There are glutamates, the amino acids responsible for the umami flavor, in human milk, but no one needs to know the science for the shot to work. Rather, it would seem that Itami is suggesting that a sort of Oedipal hunger is what truly links his characters, driving them to eat with the kind of fervor they express throughout the film.

And this is where Itami’s logic differs wildly from that of Lucky Peach, so often coolly analytic and reliant on science: In Tampopo, the drive to consume is a form of lust, and the line between eating and fucking is a blurry one. Whereas Chang turns to science to rethink traditional processes in food, Itami’s has his characters, a gangster and his moll, quite literally fuck with the classics. Canonical preparations like prawns cooked in Cognac are turned into sexual foreplay, the flailing of the booze-drowned crustaceans an erotic caress. In a flashback, the gangster is shown meeting the girl as a pubescent oyster diver. She offers to shuck a bivalve for him when he cuts his lip on its shell. Their eyes meet, then fix on the bloodstained mollusk, and he laps it up from her hand.

Conversely, Bourdain’s film column in Issue 3 is titled “Eat, Drink, Fuck, Die,” an odd headline for an essay that examines two films about food and love/lust (Eat Drink Man Woman and Babette’s Feast) and two about food and death (Munich and La Grand Bouffe). He does indeed strikeout the “fuck” in Ang Lee’s Eat Drink Man Woman, which shows a growing divide in Taiwanese society by contrasting the contemporary sexual relationships of three Taiwanese sisters with their father’s gorgeous and very traditional cooking. Instead of digging into the very engaging world of the film, Bourdain uses it as an excuse to question the clichéd idea of cooking as an act imbued with “love” or “soul.” Babette’s Feast gets a similar treatment: After stating that “I’m not so sure that food is inherently sexy—though the body provably reacts similarly in anticipation of both sex and a good meal,” he goes on to decry the reliance of some food writers on cheap sexual metaphors like the coinage “foodgasm.”

Following Bourdain, Lucky Peach only acknowledges the connections between sex and food when science says it’s okay to do so. Presenting that information as fact, as impassive logic, allows the publication to avoid bringing more uncomfortable ideas, like the Oedipal aspects of cooking and eating or the equally logical implication of a postprandial shit, into the conversation. But I find the implicit argument of Itami’s final shot to be more compelling. It may be an oversimplified explanation of human obsessions with food, but it is an appealing revision of the family-rooted arguments so often made about dining and comfort. It’s not mom’s chicken soup or pot roast we pine for, not a Remberance of Things Past. Rather, we’re searching to fill a void left by a more primal pre- memory and its loss.