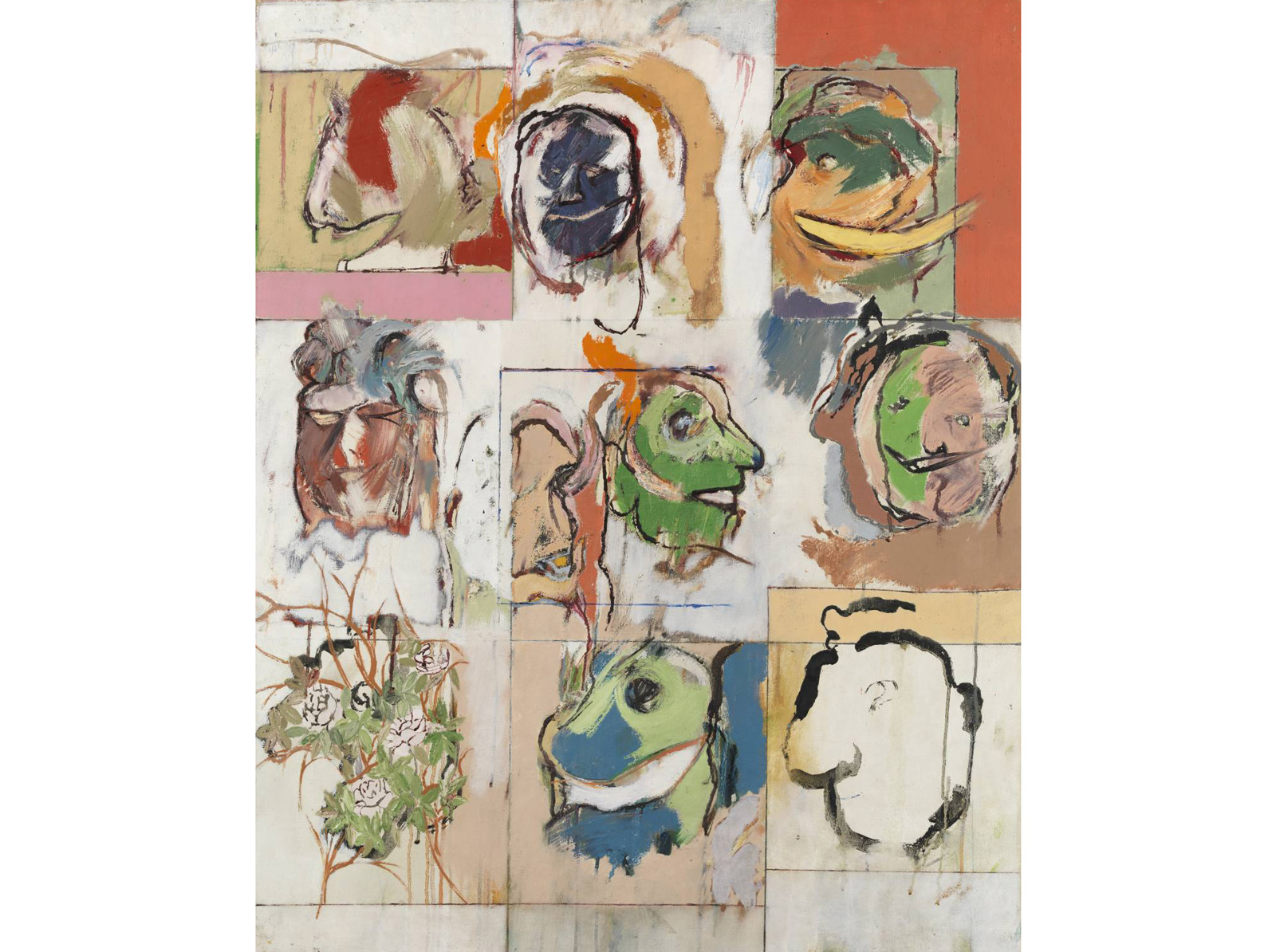

In 1989, the Jewish painter R. B. Kitaj published his aesthetic philosophy in his book, First Diasporist Manifesto. In the manifesto, he describes “diasporism” as “an unsettled mode of art-life” rooted in the rootlessness of a diasporic artist. The diasporist’s experience of dislocation becomes a creative resource for an art form that embraces restlessness and dispersion, treating the diasporic condition not as a deficiency but as a realm of possibility. Diaspora is creatively generative; diasporist art—for Kitaj, both a way of painting and a way of living—is what it generates.

Bruno Schulz (trans. Madeline G. Levine), Collected Stories. Northwestern University Press, 2018. 288 pages.

More than two decades earlier, in 1967, Jacques Derrida, too, considered the aesthetic fecundity of diasporic Jewishness. In “Edmond Jabès and the Question of the Book,” Derrida links the figure of the Jew to the figure of the Poet and describes the Jewish relation to language as inherently diasporic. For Derrida, exile is the source of Jewish poetic creativity, which arises from a diasporic longing for a homeland that does not conclude in the attainment of a nation. Because this longing looks forward without the intent of culminating in the return to a homeland, it is inexhaustibly generative—an ever renewable “adventure” of continually deferred fulfillment.

Twenty-five years before the publication of Derrida’s inquiry into diasporic Jewish poetics and forty-seven years before the release of Kitaj’s diasporist manifesto, Bruno Schulz—a writer of the Jewish diaspora—was murdered by a Gestapo officer while carrying a loaf of bread to his home in Drohobycz, the small Polish town where he spent nearly his entire life. During his lifetime, he published two remarkable books of strange and stirring stories. He left behind another book of four longer stories and the manuscript of an unfinished novel titled The Messiah, entrusted to unknown persons he described only as “Catholics outside the ghetto.” All of this work has been lost.

Schulz’s literary legacy is fractured; absence lies at its heart. In Regions of the Great Heresy (first published in Polish in 1967), a collection of biographical and critical essays on Schulz, Jerzy Ficowski—a Polish poet who, after an early encounter with Schulz’s stories, became an expert on his life and a champion of his work—laments this situation. “Most likely,” he writes, “Schulz’s major work would have been the now lost novel Messiah, in which the myth of the messianic coming was to symbolize a return to the happiness of perfection that existed at the beginning of time.” But the incompletion of Schulz’s oeuvre has not undermined interest in it. Rather, it has fueled it. Philip Roth and Cynthia Ozick, two of the major American Jewish writers of the 20th century, each penned novels that stem from Schulz’s murder and the loss of his work. Roth’s The Prague Orgy (1985) concerns Nathan Zuckerman’s journey to Prague in search of the manuscripts of a murdered writer based on Schulz, while Ozick’s The Messiah of Stockholm (1987)—dedicated to Roth—follows a Swedish man who believes himself to be Schulz’s son and who happens upon what might be the lost manuscript of The Messiah. The tragic truncation of Schulz’s life and the destruction of much of his work have given both his life and his work a diasporic incompletion that has proven aesthetically generative.

Most of Schulz’s extant work has been available in English since 1977, when Celina Wieniewska’s translation of his second book of stories, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, followed her translation of his first, published as The Street of Crocodiles in 1963. These translations introduced Schulz’s work to the English-speaking world, but they were always inadequate. In the introduction to her English translation of Ficowski’s Regions of the Great Heresy, Theodosia Robertson writes that Wieniewska’s translations, though “readable,” are insufficient. They succeeded in spreading familiarity with Schulz’s stories only at the cost of simplifying them. “It is time,” Robertson wrote in 2003, “for a more precise translation, one that does not simplify Schulz’s imagery or universalize his references.”

Collected Stories, a new translation of Schulz’s oeuvre by Madeline G. Levine, aims to be exactly this. In an introductory note, Levine praises Wieniewska’s translations, in which she herself first read Schulz, for their “undeniable magic.” But she also identifies the sacrifices Wieniewska made in the name of accessibility. Wieniewska’s translations “convey the visual images and often bizarre events that distinguish Schulz’s stories” while “taming his prose” and by more or less abandoning “the linguistic tics and mannerisms of Schulz’s style.” By naturalizing Schulz’s prose, Wieniewska aimed to ease the burden on English readers. But this choice risks obscuring what is distinctive in the work. By contrast, Levine’s renderings privilege fidelity. She aims to capture Schulz’s prose style by mimicking his frequent use of alliteration and repetition and “by stretching English syntax to make it accomodate the sinuosity of Schulz’s longer sentences rather than reining them in.”

While Wieniewska contorted Schulz to accommodate him to English, Levine deforms English to accommodate it to Schulz. Wieniewska made Schulz’s foreignness familiar in a way that forced his work to assimilate into English; Levine, by reproducing Schulz’s linguistic idiosyncrasies, attempts to preserve his outsider’s relationship to his own native tongue, which is tied to his diasporic Jewishness. (The Jewish thinker Franz Rosenzweig writes in The Star of Redemption that “the Jewish people never identifies itself entirely with the language it speaks,” which gives Jews in the diaspora unique vocabularies, syntaxes, and aesthetics.) And, in a seemingly simple move, Levine’s translation—which comprises Schulz’s two books of stories and four additional uncollected tales—restores to Schulz’s first book, until now published in English under the title The Street of Crocodiles, a direct translation of its original title: Cinnamon Shops. It is fitting, too, that the collection, which could easily have been called Complete Stories, instead bears the name Collected Stories. This choice gestures, however subtly, to the fundamental incompletion of Schulz’s work.

To read Schulz’s Collected Stories is to immerse oneself in the Schulzian cosmos: a fictionalization, even mythologization, of Schulz’s hometown of Drohobycz. Like Schulz’s life, the stories take place almost entirely within the city limits. Nearly all of them are narrated by a young man named Józef, Schulz’s alter ego. They focus on Józef, his father Jakub—a fascinating, domineering figure whose life is split between his occupation as a merchant and his fantastical experiments—and the family’s servant girl, Adela. The tales, mostly short, take the form not of fully developed narratives but of brief glimpses of Drohobycz. They tend to center on some season, character, object, or area of the town and digress from there. Not a few of the tales end with ellipses; those that don’t feel as if they easily could.

Though Schulz’s setting and form are largely fixed, his imagination seems boundless. Levine’s rendering of Schulz’s prose captures its bewildering sensuality. Consider the second, single-sentence-long paragraph of “Autumn,” the first story in Cinnamon Shops:

Adela would come back on those luminous mornings like Pomona from the fire of the blazing day, pouring from her basket the colorful beauty of the sun—the glistening sweet cherries, full of water beneath their transparent skin; the mysterious dark sour cherries, whose aroma far exceeded their flavor; apricots whose golden flesh held the core of long afternoons; and next to this pure poetry of fruit she would unload racks of flesh with their keyboards of veal ribs, swollen with energy and nourishment; seaweeds of vegetables that resembled slaughtered cephalopods and jellyfish—the raw material of dinner with a taste as yet unformed and bland, the vegetative, telluric ingredients of dinner with a smell both wild and redolent of the field.

This blindingly vital vividness is characteristic of Schulz’s fecund style. All is alive, growing, and passing from one state to another. In “A Treatise on Mannequins; or, The Second Book of Genesis,” Józef’s father explains his theory of matter to Józef and Adela. “All matter,” he says, “flows from the infinite possibilities passing through it in faint shivers. Awaiting the life-giving breath of the spirit, it overflows endlessly within itself, tempts with a thousand sweet curves and the softness it hallucinates in its blind imaginings.” Józef’s father—and with him Schulz—embrace matter. They “love its discord, its resistance, its scruffy shapelessness.” Józef’s father explains that, while the “Demiurge was fond of refined, splendid, complex materials,” they instead “give pride of place to tawdry.”

Indeed, Schulz’s tales, uninterested in the synagogue, are enamored with the city streets. There a more pressing, heretical, and appealing divinity arises. Józef is at his happiest wandering those streets in an imitation of the productive purposelessness that Schulz, in the story “Spring,” describes as “the wandering, luminous ravings of matter.” Schulz’s diasporist vision counters the understanding of the diasporic Jew as a cursed exile longing for a return to a holy land overflowing with milk and honey; in Schulz’s stories, milk and honey abound in exile. Appropriately, for Schulz the mundane is redolent with the divine. In “The Book,” Józef discovers in a page of advertisements torn out of a local weekly “the Authentic, a holy original, even though in such a profound state of humiliation and degradation.” In “Spring,” he has an ecstatic experience with his friend’s stamp album, which reveals to him the extent of the world beyond the territory governed by Franz Joseph I. This “vision of the flaming beauty of the world” opens up “the infinite possibilities of being.” The multiplicity of nations reveals to Józef “the possibilities swarming within” God—a diasporist vision of the divine’s diffusion.

But Schulz’s work does not present an uncomplicatedly positive picture of diaspora’s generative beauty. Absence, brokenness, and aberration obsess Schulz. At times the representations of these themes are tragic and horrific. “Father’s Final Escape” finds Józef’s father slowly dying by fading away into a room until he suddenly transforms into “a crab or a large scorpion,” whom Józef’s mother boils and serves on a platter. He returns to life and wanders away, leaving behind a leg in tomato sauce.

In “Birds,” Józef’s father raises a horde of exotic birds that Adela inadvertently releases; in “The Night of the Great Season,” the final story in Cinnamon Shops, the descendants of those birds return, deformed—two-headed or one-winged or otherwise transformed. Józef likens the birds to an “exiled tribe” that has been beckoned back to its ancestral homeland. The citizens of the town—who, earlier in the story, are compared to the stiff-necked Israelites of the Hebrew Bible—cast stones at the birds until they’re reduced to “strange, fantastic carrion.”

This story has a neater, more parable-like structure than most of Schulz’s tales, and it’s tempting to try to extract from it a simple moral about exile and return by directing one’s sympathy toward either the physically deformed birds or the spiritually deformed townspeople who hastily strike them down. But Schulz’s celebration of transformation suggests that his own sympathies lie with Józef’s father, who, in his disquisition on the fecundity of matter, posits this heresy: “Every organization of matter is impermanent and unfixed, easily reversed and dissolved. There is no evil in the reduction of life to new and different forms. Murder is not a sin. Often, it is a necessary act of violence against unyielding, ossified forms of being that are no longer satisfying.” Schulz’s fictions seem to mimic this amoral position. The diasporism of Schulz’s stories is not some sentimental celebration of Jewish life in the diaspora but rather an interpretation of exilic existence as overflowing with life, beauty, tragedy, and decay—all interwoven and inextricable.

In the final year of Schulz’s life, his beloved hometown of Drohobycz was transformed into a prison. In 1941, Drohobycz fell under Nazi occupation. Schulz, along with the rest of the Jewish population, was forced to don a yellow star and was forbidden from working. In addition to his writing, Schulz was an accomplished visual artist—he had made his living as an art teacher—and his artwork caught the interest of Felix Landau, the Gestapo officer assigned to manage Jewish affairs in the Drohobycz Ghetto. Landau began commissioning work from Schulz. This earned him the classification of a “necessary Jew,” a designation that protected him from deportation to the camps. But this relationship ultimately led to his death. On November 19, 1942—the very day Schulz, who had just received forged papers to facilitate his escape from Drohobycz, planned to depart—he was shot to death by a Gestapo officer named Karl Günther as part of a long-running feud between Günther and Landau, who had recently murdered a Jewish dentist whom Günther favored. Günther, when he next saw Landau, reportedly proclaimed: “You killed my Jew—I killed yours.”

Of all Schulz’s output that was lost during this period, the only work that has since been recovered emerged from his arrangement with Landau. In 2001, a documentary filmmaker discovered a series of murals Schulz painted, hidden beneath layers of paint in the home where Landau once lived. The murals, which depict fairy-tale scenes, decorated Landau’s child’s bedroom wall. With the aid of art historians and preservation specialists, the fragmentary remains of the murals were authenticated and, to some extent, restored.

But before there could be any serious discussion about where the works would be housed—in now Ukrainian Drohobycz, in Poland, or elsewhere—they were seized in secret by representatives of Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to victims of the Holocaust. A scandal erupted. What right did Yad Vashem have to unilaterally claim ownership of Schulz’s works? In Regions of the Great Heresy, Ficowski describes the argument made by Yad Vashem’s spokesperson, Iris Rosenberg, who insisted that “the paintings are better off in Jerusalem because their proper place is there.”

Yad Vashem’s claim to Schulz’s work over and above the claims of the town in which Schulz lived, worked, and died and of the nation whose language he spoke and wrote in suggests a rejection of Schulz’s diasporic Jewishness and of his work’s diasporism. If Schulz’s work is indeed most at home in Jerusalem, then neither Schulz nor his work were ever truly at home in the diaspora.

The logic that underpins Yad Vashem’s invalidation of Schulz’s diasporic Jewishness is as old as the ideology of Zionism. Indeed, the Zionist narrative denies the very possibility of authentic diasporic art. The rejection of any Jewish artistic flourishing in the diaspora recurs frequently in Zionist discourse, from the early Russian Labor Zionist A. D. Gordon to David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, both of whom argued that the alienation of exile precluded the emergence of vibrant Jewish cultural life. The possibility of profound diasporist Jewish art such as Schulz’s poses a threat to the Zionist narrative, in which Jewish cultural, artistic, and imaginative flourishing is possible only in a Jewish state.

The transportation of Schulz’s murals from the city that was his home and muse—the city that Józef, in Schulz’s story “The Republic of Dreams,” describes as “this chosen region, this singular province, this city unique in all the world”—to the so-called eternal capital of the Jewish people is an attempt to complete Schulz’s work. But that work is essentially incomplete, and it refuses to understand incompletion as anything other than profoundly generative. Schulz the diasporist embraced the beauty in exile, dispersion, and decay. It is no one’s place to bring his fragmentary wanderings to an end. Better that we continue to wander beside him and, in his name, wander anew—awaiting the return of his Messiah, but content with the knowledge that it will likely never come.