A conversation with not-novelist Masha Tupitsyn about her new book Love Dog

In November 2011, the writer and critic Masha Tupitsyn started a blog called Love Dog. Like she said at the time, her stance was Hamlet’s: “You don’t let go of your object.”

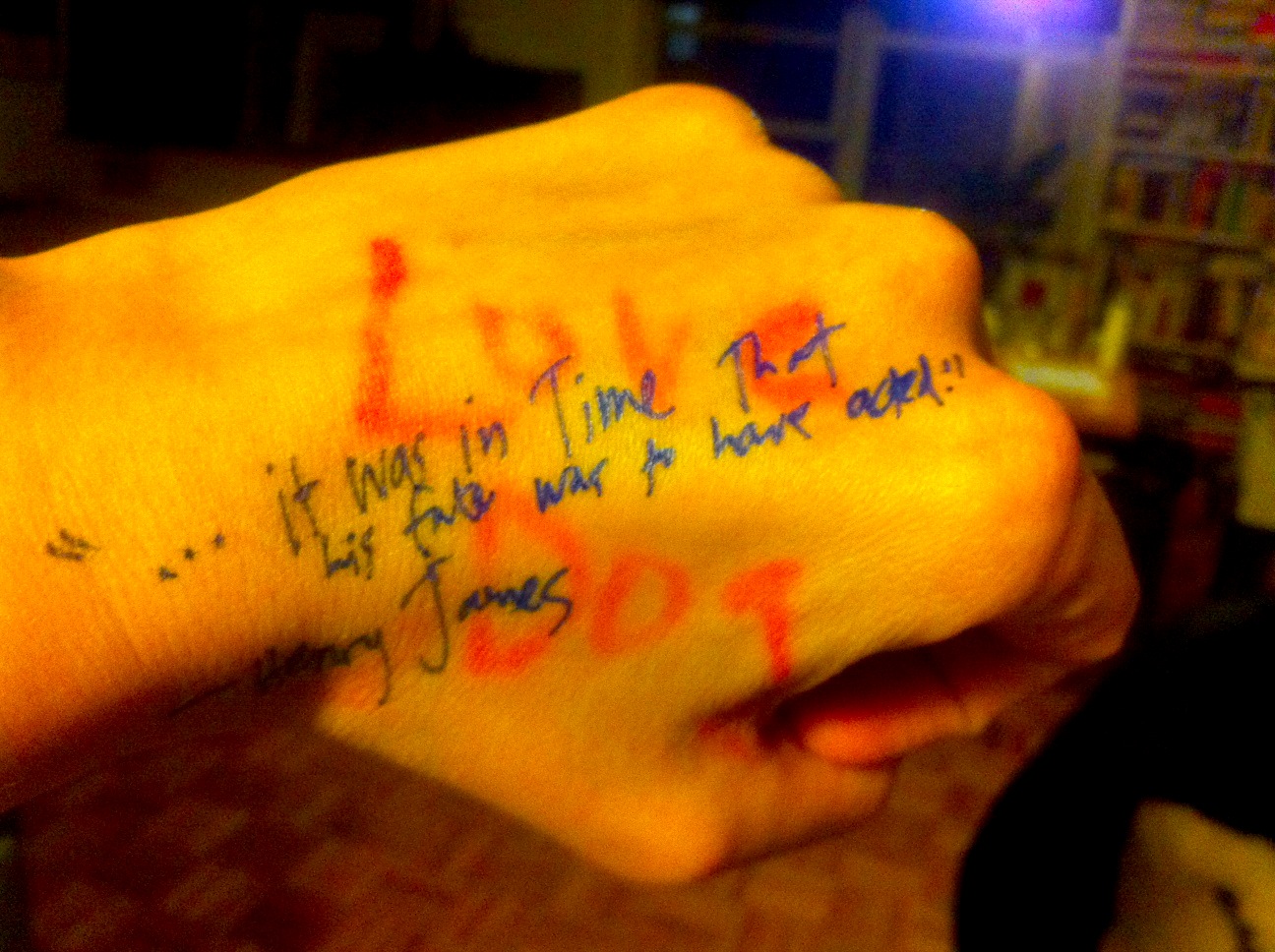

Love Dog — now also a book coming out soon from Penny-Ante, and the second volume in Tupitsyn’s trilogy of immaterial writing — is a project about love in the digital age, feminist love, and mourning. It is also a good read, lit through with '80s songs, red and green, tarot’s fool, screenshots, time jumps, and a tough, elegant shyness. (Like Bowie, Tupitsyn knows “when to go out and when to stay in.”) It is a multimedia notebook, pieced out in day-sized chunks like it was originally, on Tumblr. First, though, Love Dog is a call to love, all the stronger and wiser because Tupitsyn’s heart has been broken too.

Her object is X.: “The person for whom I read everything now and will write this year, making the ‘you’ into a world.” Tupitsyn’s X. is not foggy, or a narcissistic cipher, but an actual person who is never named. And as Love Dog picks up speed, Tupitsyn writes too to her mother, to her dear friend Elaine Castillo, to books, cities, and others.

Though I see why Tupitsyn does not call herself a novelist, I’m going to keep Love Dog on my shelf next to Chris Kraus and Herta Müller anyway. Like their books, Love Dog is one you can enter at any point, yet is still cohesive and wholly of itself.

Masha and I chatted by email in late May and early June 2013.

Mairead Case: Two summers ago, we talked about LACONIA: 1200 Tweets on Film, your first piece in this digital trilogy, for Bookslut. I complimented you on how connected your books are. They are all obviously in conversation with one another, even when their form and tone are different. You said the seamlessness of that process is an illusion — that while you do make lists of the books and essays you want to write, you don't always know how you're going to get there. That you come to things in a roundabout way and don't always see the arc until later.

I get that, as both a reader and writer. But still, Love Dog seems to braid your interests together more than ever before. You quote your short fiction, you add codas and footnotes to previously published books and essays, you find epigraphs for future projects. I was struck by how much you mention faces, and John Cusack, two projects I know you’re working on for the future. How do you decide where one project begins and another ends? Has this process changed at all since we last talked?

Masha Tupitsyn: It's true, my texts are woven, both thematically and formally. That's how they get made. The form weaves the content and the content dictates the form. Both Love Dog and LACONIA also archive the work of work — the making of work, the preparation of future work, the meaning of past work, which can sometimes only happen in retrospect. So themes and ideas naturally recur. I don't want there to necessarily be any hard or clear line between each book. I want things to mesh and overlap. And it's a trilogy, so it's precisely about not knowing where something begins and ends, or what beginnings and endings are anymore. With my forthcoming book, Screen to Screen, I could not write that book head-on, in one shot. I tried, but it didn't work. Because my criticism has been evolving over the years, and also because I had to write these other books in between in order to write Screen to Screen. So those books trained and prepared me. The Hamletian "readiness is all" is sort of the key here.

As far as my writing process since LACONIA is concerned, it hasn’t changed all that much, just crystallized. LACONIA set me on course. My writing approach became clearer to me with that book. I still have my list of projects that I want to see to fruition. But I often have to work my way up to being able to write something. The more I understand the way I think and work, the better I become at doing what I want to do. I have more control and craft and confidence now while also trying not to exploit those techniques, discovering and exploring them instead. I always want to be surprised by what and how something happens. This may sound cryptic, but you have to do a book when you feel it can be done. And sometimes, most times, writing one book makes another book possible. You have to pass through one to get through another. Some texts are more pressing and press harder on us than others. So part of writing is figuring out when and how to write. Writing a book is an intuitive process. You have to be rational and disciplined about it, but you also have to feel your way around.

MC: One wonderful thing about your digital writing, especially for readers like me who follow online first, is its proximity and, as you write early on, its polyphony. For example, I've connected to scenes in Robert Bresson movies I'm actually watching for the first time, because you posted clips on your blog. Even while prepping for this interview, I shut off the computer for a quick thinking nap while looping Daft Punk's "Make Love," which you write about falling asleep to in Love Dog after a night out with X. It's like the book was surrounding me.

When you jump from Twitter to manuscript or Tumblr to manuscript, how do you decide what to cut or focus? And because writing is your life, as you've said, even as a private person, do your books ever surround you like this too?

MT: I love the idea of the book having a sound and jumping, like a leap of faith. And it did surround me. That’s really the best way to describe the experience of not only writing the book but also why I needed to write it. Ears, listening — receptivity — are recurring tropes in the book, as you know. In the first half of Love Dog — Part I (Hope), I was surrounded by and immersed in the ontology of signs: the things I was seeing, hearing, and reading. Everything felt inspired and magically aligned. So I wanted the book to reflect that attunement. I think of Love Dog’s musical playlist as giving tonality to the book’s ideas and feelings. That’s why I state in my note to the reader that Love Dog is a book you have to listen to, watch, and read. Also, as Godard put it, “To me there is no real difference between image and sound … You have to listen to the image and look at the sound.”

It was easy to edit Love Dog because I was pretty obsessive about its construction from the start. Because I have no interest in using social media without staging some kind of critical/creative intervention, everything was weighed carefully. Second, in order to execute this series of immaterial writing, I had to establish some rules and principles of writing, a Oulipo influence (freedom in the form of constraint). I had a system while also making discoveries along the way. I deliberated over each post, allowed myself only to post once a day, made lists of the order the posts would go in advance. Long posts were queued in my draft box. Sometimes entries were totally spontaneous and sometimes it took me a few days to finish an essay. During the first big edit for the book, I edited out maybe 50 posts — anything that felt thin or nonessential. Then, once I saw the first proof and it was all laid out for me on paper, I fine-tuned the arrangement even more because I could really see the shape then. In a few cases, I moved things around slightly because I could see a better fit and I wanted everything to slide into place.

I never thought I would have a blog and resisted it for a long time. And yet despite my ambivalence about the Internet, I wanted to write about love in some roundabout, multi-track, uncategorizable, contemporary way, which is how I was experiencing it, and Tumblr allowed me to write the kind of multi-modal and discursive criticism that I have always wanted to write. Writing in the digital age is a very bittersweet practice for me. On the one hand, I feel excited and liberated by the possibility of form. On the other, I use the form precisely to locate and enact cultural mourning. Both LACONIA and Love Dog are digital ripostes as well as thought catalogs. I wanted to write a book that would respond to the digital structure that organizes our daily lives today: a fractured, multimedia love narrative that reflected the fall of narrative. When all we have is precarity and the present, there is no catharsis, resolution, or stability.

How do you see Love Tests/Love Sounds, the final installment in this, your trilogy of immaterial writing? How do you think future audiences will know this trilogy as a whole, since it incorporates so many different media?

That’s a good question, I don’t know. Technology is in such rapid flux, so I don’t know what exactly will be possible in the future. The trilogy’s wholeness might be more conceptual than tangible. It is an immaterial series, after all. My dream is for Love Dog to exist in print and as an app, so that people can download the book and read it in its digital form. Love Tests/Love Sounds is an audio history/montage of love in cinema. Formally, it’s inspired by Andy Warhol’s silent film series, Screen Tests, as well as Warhol’s late '60s novel, a: A Novel, made from audiotapes recorded in and around The Factory. Conceptually, it will consider not only the way people think about and experience love but the way love sounds. This is interesting if we think about courtly love in medieval Europe, tropes that Love Dog plays with in a number of ways. In the tradition of courtly love, nobility was tied to expressing love — performing it, speaking it, declaring it. While there is a lot of emphasis placed on the visual representation of love in cinema and TV, with the exception of music, which is more atmospheric than conscious, there is very little attention paid to the aural aspects of love as it exists today. The project also takes its cue from the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy’s important question in his book, Listening, where he asks, “What does to be listening, to be all ears, as one would say, ‘to be in the world’ mean?” I think listening is where we need to be heading at this point. We’ve been far too invested in scopophilia, and we’re very near sighted as a culture because of it.

Thinking about your epigraphs, from Mishima and Kathy Acker, did you ever consider yourself a novelist? And as a whole, how do you see Love Dog connecting to Acker? You talk about her a lot in all different parts of the book.

I never considered myself a novelist in any classical or literal sense, no. Having said that, every book or film can be read against its own self-declared genre, and will be, and is. Things are culturally determined and (per/re)ceived, so regardless of what a writer actually calls their book, someone else can call it something else. It’s the problem of genre — giving something a name doesn’t always mean that it’s its only and proper name. It’s the name it goes by in order to exist in the world. It’s the identity card it uses. But everything has a secret or double name, too — a name people can’t always recognize right away. I talk about self-naming at the beginning of Love Dog, in relation to the title.

I’ve also talked a lot about how categorization often changed the way people received Beauty Talk & Monsters, my first book. That when I called Beauty Talk a collection of essays, people accepted the book more than when I called it a book of stories. Non-fiction created a wider net of acceptance. That was strange to me. So what’s in a name? Everything apparently. Some people called Beauty Talk a novel when referring to the book, and that makes sense, because the pieces are certainly interconnected and thematized. There’s a strong thread. So honestly, every book of mine can be read as an experimental novel, of course, just as my book of modern-day aphorisms, LACONIA, can ultimately be read as one long essay or manifesto. It’s also an autobiography, as Chris Kraus pointed out.

So the rules we continue to apply to the novel no longer make sense. They’re antiquated. If you want to read traditional novels, by all means, read them. But why should we be expected to keep writing the way we did in the past when the world is a different place and therefore requires a new language to describe it? Those books were responding to their time, so today’s books should do the same. The novel, like the rest of the world, has become completely unstable, and it should reflect that in order to stay relevant. And while we accept new ideas that use old forms, when it comes to literature, which is behind the other arts, we are resistant to accepting old (and new) ideas in new forms.

In the book, I am a woman in love, on a quest, wounded, a thinker in pursuit of truth. These are all genres of truth procedure and inquiry and becoming-subject that have been historically monopolized by men. But I am also a critic grappling with the content of the world I live in. For me, mass media is the allegorical battle of today.

When we talked for Bookslut, you said your dream was to teach a class you designed yourself. Is that still a goal, now that you're earning your doctorate? What would the class be about, if you taught it tomorrow?

Teaching itself is not the dream per se. But teaching certain ideas, texts, films, and approaches is. As of late, I’ve been making a list of films for a class on screen doubles. The course would look at cinema as an uncanny zone by pairing two films together as if they were a couple. Considering things like influence, haunting, echo, return, repetition-compulsion, and cultural memory, we would look at what connects films in a deeper sense; how two movies can work as an aesthetic or political couple — or anti-couple. It would ask students to read things in discursive and associative ways. To see what isn’t (obviously) there, not just what is purported to be there. The Portuguese filmmaker Miguel Gomes takes the title of his film Tabu from F. W. Murnau’s 1931 Tabu because, he explains, “I have the sensation that when I’m making films, there is the memory of other films, but in a very diffuse way, not a conscious way.”

I loved "One-Dimensional Women on One-Dimensional Feminism," one of the essays in the book, which is a response to Nina Power’s One-Dimensional Woman. In your essay, you write "Feminism is no longer a lifelong struggle or commitment to social justice. It's something you have to be until you no longer have to be it ... loving ourselves in the way that loving ourselves has come to be defined is overrated, privileged, and self-indulgent." I love too that you wrote this when you call yourself a feminist, in a book where you quote writers like Judith Butler, bell hooks, Fanny Howe, Jeanette Winterson, Kathy Acker, Audre Lorde, Sarah Schulman, Sarah Ahmed, and Avital Ronell.

Thanks. The title could work in reverse! I think feminism needs to be racially, politically, sexually, and culturally diverse, but it has to have some set criteria in order to be a common struggle that remains critically vigilant. If feminism is everything and anything, then it’s nothing. Then you can exploit anything in the name of feminism, as Power points out. As I write in the essay, the word feminism has been so bastardized and deflated — used for everything and by everybody for the most cynical, self-serving, and often incompatible reasons. So I think both the word and the struggle as a whole have to be reimagined, radically repoliticized, and rescued from the miasma of consumer capitalism. Feminist capitalism, for example, is a total oxymoron to me, as what can be radical or liberating about capitalism in its current disastrous and criminal form?

Equally, I don’t feel that self-esteem should be about loving oneself. Rather, it should be about self-worth and self-actualization. It should be about loving the Other, which requires self-vigilance. My job as a human being is to take care of myself and others. To value myself, not to self-destruct, and not destroy others. But it’s not to love myself. It’s for other people to love me, and for me to love other people.

At the beginning of Love Dog, you explain how you need "an addressee — someone to whom I write, and just one is enough—because everything I write is really just a letter to one." This refers to X., the book's romantic muse, the catalyst for the project, who at first I understood like Barthes’ X. in Lover’s Discourse (a key text for Love Dog along with his Mourning Diary, just as Notes of a Cinematographer was key for LACONIA). But then of course your X. is also someone you know. He is real, despite being absent. So the question of the addressee concerns your approach to writing as well as your approach to love. The two are fused — the text as lover and beloved. Can you talk a bit more about your X?

Like LACONIA is an ode to the laconic, Love Dog's One is a nod to minimalism, to less is more, to Bresson’s “To have discernment (precision in perception).” Writing for one, having an addressee, sets up an intimate relation and critical discernment that is important in a book about radical love, I think. But one doesn’t literally mean one. It means that in the process of writing I am trying to create a model of relational intimacy. It doesn’t mean that only one person will read the book or connect with it. It means that whoever is reading the book will hopefully feel that the book is for them — or for their one, whatever and whoever that one is. That the book itself is a gesture of closeness.

And ideas are treated similarly. This is why I show the texts that I am working through, reading, and thinking about. The footnotes, addendums, quotes, running commentaries, references, recurring motifs, links are all meant to show that I am not interested in creating a hermetically one-dimensional text that leaves its construction at the door, as it were. I’m interested in diegesis and assemblage as well as the thinking process itself. Using a multimedia format makes Love Dog a text of interstices and marginalia. Love Dog goes behind its own story, it footnotes it, tells it and retells it from different angles and times; sometimes textually, sometimes visually, sometimes in song, sometimes in quotes. The book wants to remember, mourn, yearn, archive, catalog, and dissent all at the same time.

But you are also writing to your friend Elaine and your mother, which made me remember how your teacher Avital Ronell wrote about Kathy Acker in Lust for Life. I also like how this intimate One dovetails with your critiques of the Internet: how it's endless and promiscuous, and you’re working against that. How people forget to say things to people.

Autobiography, confession, etc., today are sort of useless to me without a relation to the Other. A lot of Internet writing operates as a space of purging. In most cases, there is only an “I.” Not even an “I,” a “Me.” I know that is seen as a positive, transgressive, and feminist thing for many writers and readers at the moment. But it isn’t always, and it isn’t inherently. I am not advocating the symbolically anorexic model of feminist writing either — deprivation vs. excess. But why does it always have to be one or the other or to the extreme? And why does the space of writing have to be so egotistically lawless? The Internet has radically changed the domain of writing and the poetics of creative space, so that it's more often about the where and when of writing, and less about meaningful or radical content.

I feel like a lot of writing (and people, too) is so antisocial right now, and one of the downsides of blogging, and the Internet, as liberating and inventive as it's been for writing, is this throwaway relation to language, thinking, subjectivity, time. That was yesterday, this is today. I was this person, now I’m this person. There is no consistency or integrity much of the time. It’s very juvenile and self-indulgent. Antisocial doesn’t simply mean you don’t want to see anyone. You can be intensely antisocial within your sociability and vice versa. That’s why so many people think it’s okay to stare at their cell phones while they’re with company. Or live with partners without talking to them. All this writing and utterance is sort of in place of the material social we’ve lost — what you describe as people forgetting how to say things to each other, how to listen, how to take things in, how to be present with others.