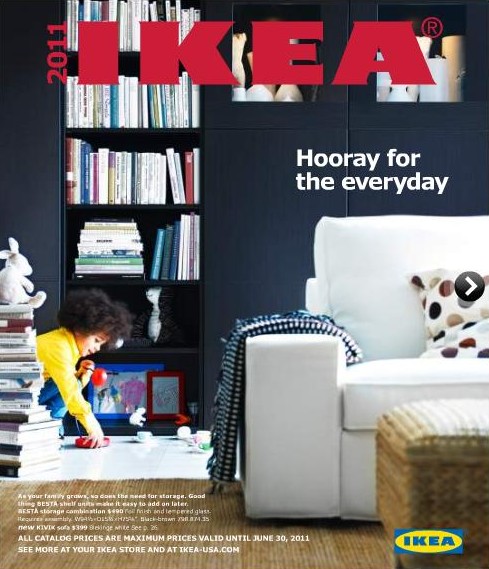

I was about to recycle the Harry Potter-length 2011 Ikea catalog when the copy on the cover caught my eye: “Hooray for the everyday.” Next to a shelf of decorative Scandinavian literature and a child of indeterminate ethnicity, the white words hang like an inexpensive piece of Ikea art — a sort of postmodern crocheted plaque, only instead of “Bless this home,” there is a cloying embrace of the quotidian. In the midst of economic crisis and sinking uncertainty, what is Ikea trying to say? When Ikea shouts “Hooray for the everyday” from its catalog cover, I fear today’s everyday is different than yesterday’s.

One of the consequences of crisis is that the everyday ceases to exist as such. No one knows what will happen tomorrow or the next day. These kind of conditions make it hard to shop or construct your new Scandinavian furniture in peace. Thomas L. Friedman, in a recent New York Times column summed up the present moment well: “It’s like this: things are getting better, except where they aren’t. The bailouts are working, except where they’re not. Things will slowly get better, unless they slowly get worse. We should know soon, unless we don’t.”

He concludes with a plea for an answer — any answer! — from the Obama administration. With all this uncertainty and sky-high unemployment, it’s a tough market, even for cheap-and-stylish furniture businesses. Orthodox economic theory tells us that people who don’t know if they’ll have a job in six months are less likely to buy couches. Even cheap and stylish couches.

Considering the threat of falling consumer demand, Ikea and the federal government find themselves engaged in the same task: convincing us that things have returned to normal, even if that normal isn’t the one we are used to.

This idea of the “new normal” has entered popular discourse, mainly through the work of Nobel laureate economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman. In his August 1 column “Defining Prosperity Down,” Krugman predicts that authorities could declare current levels of unemployment “structural” and make no further effort to deal with the problem. He attacks the Federal Reserve – an organization that has the distinct honor of attracting the ire of Congress’s only open socialist (Sen. Bernie Sanders) and its fiercest Randian (Rep. Ron Paul) – for failing to aggressively pursue full employment. The counter-argument Krugman critiques, that unemployment is due to the business community’s fear of coming regulations and therefore not the Fed’s responsibility, reeks of the same conservative ideology that left former Fed chair Alan Greenspan apologizing on the House floor to the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. New chair Ben Bernake has proven less “change we can believe in” and more Greenspan with a cool beard.

In ocean ecosystems, heavy metal contaminants concentrate in the upper trophic levels as predators accumulate from their prey. The new normal is the inverse, limiting the effects of the demand crisis to a swelling class of unemployed. The 2011 Ikea catalog contains a short essay called “We’re all from Småland.”

We’ve come a long way from being a one-store company in the stony fields of Småland. At the same time, nothing at all has changed. It’s still about doing more with less, challenging convention and not letting a single thing to go to waste (good for prices and the planet)… . We’ve found people all over the world who hate to throw money down the drain. People who know that value doesn’t come from big price tags and are willing to work a little harder. People who are Smålanders at heart, just like us.

There is no language of crisis here: “nothing at all has changed.” Even though that phrase ostensibly refers to the company’s founding, it has a menacing firmness to it that sticks in my throat. “Nothing at all has changed” is an injunction as much as a history, as if followed by “Am I understood?”

We Ikea customers have been under this injunction all along: the crisis acts as a reminder of our true selves, and we are — despite all evidence to the contrary during the boom — thrifty at heart. The new normal is thus positioned as a comforting return to the Protestant work ethic, to harmony with nature. Chris Farrell describes this “new frugality” in his book of the same title in almost aesthetic terms. Being thrifty, he argues, shouldn’t be about poverty, but about feeling good in your relation to the Earth and your possessions. Farrell answers the pressing question of what to do with all the extra money you will have left over – he suggests Yoga lessons. This kind of optional frugality not only hides those most affected by the recession, but presents itself as a commodity. While the actual consequences for the demand crisis fall on the growing ranks of the unemployed, Ikea shoppers pay to simulate thrift, just as they always have.

The perfect example of the new normal may be the Ektorp three-seat sofa. The catalog explains that the sofa is now a “customer assembly piece” — also known as a “you have to build it yourself, with only tiny Allen wrenches that will totally break piece” — which has made the Ektorp more environmentally sound and cheaper. It’s listed for $599. In the 2010 catalog, though, the same couch without the self-assembly was listed for $499. Even though the Ektorp really is less expensive this year (online the base model is listed for $399, it’s an extra $200 for the pictured gray cover), Ikea doesn’t bother to list the cheaper price. One might think customers affected by a recession would be more enticed by a $200 price differential than a handsome gray cover, but the catalog isn’t for them. In the new normal frugality isn’t a simple function of cost, but an independent product feature. Despite all the rhetoric about their customers being thrifty Smålanders, the Swedes know you don’t really remember last year’s price. The guy who goes to shopping excited to pay only $599 for an Ektorp and the chance to Allen-wrench his way to environmental sustainability isn’t a sucker, just normal.