So we pick up a copy of New Directions’ new edition of Frederic Tuten’s The Adventures of Mao on the Long March at the Strand and we’re floored. It’s everything we’ve been looking for, and there it was, all along. Reading Mao aloud comes naturally: It is a theatrical text, a literary collage dramatizing its own assembly, a recipe for a good time. It is the story of the Long March, that most heroic episode of the Chinese Revolution, a mythopoeic odyssey, a fable, a newsreel, an avant-garde manifesto, a political pamphlet.

Read aloud, it has all the qualities of great theater: the capacity to simultaneously transfix the imagination and expose the apparatus of representation; the seduction by which it induces a visceral feeling of the reality of one’s co-presence with real bodies and real forces in a real space in real time; the simmering sense of potential possessed by the living act, in which we glimpse something more untimely. There are no rehearsals for this kind of encounter.

So we got together one rainy October afternoon, some of us friends, some of us strangers, all gathered in sympathy, in a smoky living room in Brooklyn. We passed out drinks and passages of text. The Long March begins.

The New Inquiry is honored to host a public reading of Frederic Tuten’s The Adventures of Mao on the Long March this Sunday, December 4, 2011, at the Jane Hotel at 113 Jane Street in Manhattan. This event, which TNI is co-presenting with BOMB Magazine, ForYourArt and sponsored by Google Places, marks the 40th anniversary of Mao’s release and the 75th anniversary of New Directions Publishing. With this event, we commemorate a work and an author who inaugurated our cultural present and may yet prove its eventual savior.

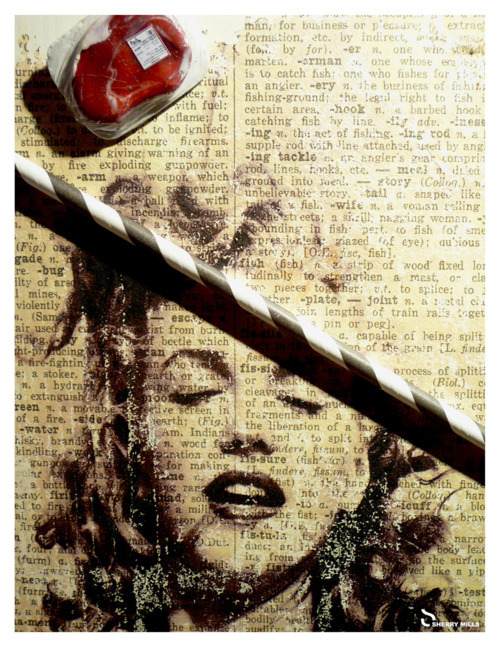

First published in 1971, Mao presents the story of the Long March in a radically experimental narrative style that freely mixes fiction, fact, citation, and parody to create a literary collage that does to the novel what Godard did to film. Separated into paint-by-numbers-like episodes, the central narrative provides a historical overview of the Chinese Civil War through the Long March that, with its openly pro-Communist perspective, reads something like C.L.R. James’s Black Jacobinsin miniature. At the center of this “history” is Tuten’s fictionalized Great Helmsman, a poet-warrior, very much the angry young man, whose titular (mis)adventures include being tempted by a talking snake, encountering Greta Garbo behind the gears of a tank, and having his artistic pretensions shattered by a literary critic. At times, Mao is ventriloquized by Pater, Ruskin, and Wilde for lengthy digressions on art theory, and the novel concludes with a 20-page imagined interview between Tuten and Mao. Interspersed throughout these sections are passages of rumbly Americana ripped from the pages of Faulkner, Hawthorne, Cooper, and London, as well as parodies of Hemingway, Kerouac, and Malamud. Also within are Yoko Ono-esque concept-art recipes and fake art reviews in which the text not only comments upon but arguably adapts to literature the great visual arts movements of its time—Pop, Minimalism, Conceptualism, and Process Art. And because no revolutionary pamphlet is complete without at least one interminable citation of Engels, dear reader, Mao will not disappoint.

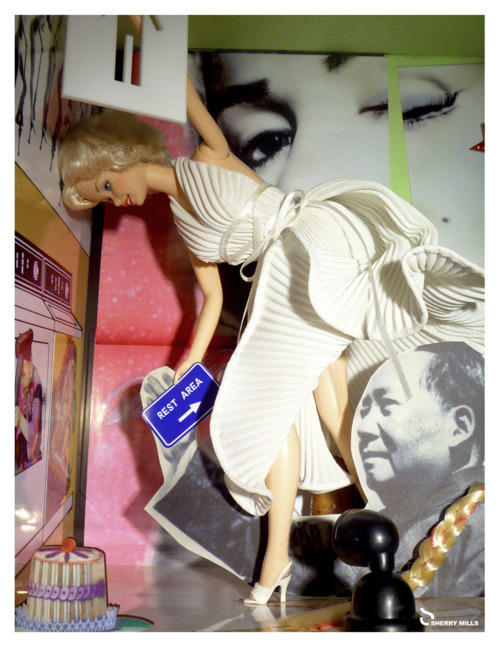

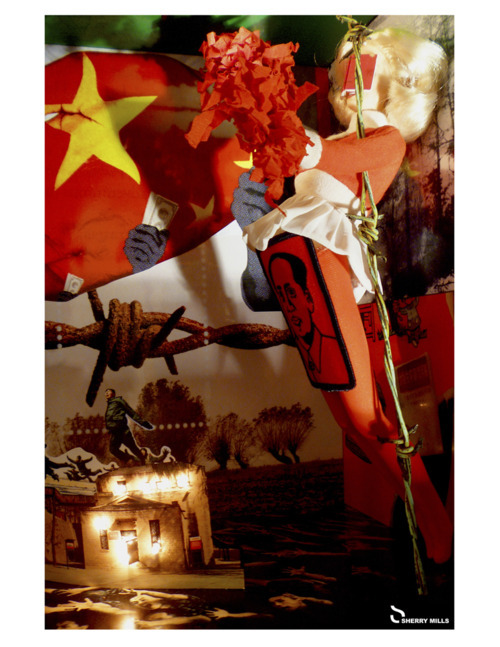

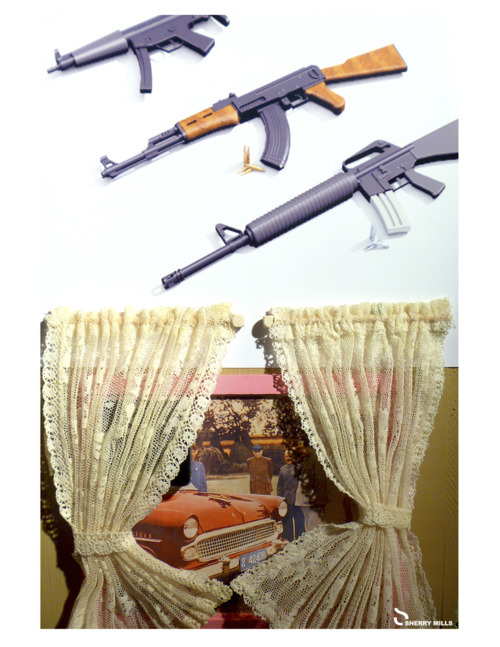

If one of the roles of art is to inject into the world what experience alone does not provide—a story, a picture, a song, a representation—and the usual role of criticism is to interpret the mess of art into concrete, intelligible meaning, thenMao represents a third way. The book does not analyze or comment on the world from the cool distance of representation; it is a stone over which the reader trips, a brick through the windowpane of the senses. Like a tornado run wild on the cultural landscape, it indiscriminately sucks into its vortex the signs, icons, and golden calves of both high and low culture, strips them of original contexts to repurpose and accelerate their semiotic punch: a roving, nomadic insurrection of art against the everyday. Mao’s lasting contribution to American literature was the realization that in the United States, riven by inequality, infused with consumerist libido, and saturated in media, such ecstatic bricolage is the art that most resembles lived experience and, therefore, is the artistic method most capable of changing it.

Mao is revolutionary as art, but it is also art in the service of revolution—that is, of a politics of liberation. It may invite the reader to take pleasure in fantasizing that Mao subscribes to October, but it also invites the reader to take an equally genuine pleasure in its account of the Red Army’s capture of the Tatu Bridge. As John Updike put it in his 1972 review of Mao for the New Yorker, Tuten likes Mao (John Updike, “Satire Without Serifs,” originally published in The New Yorker, 1972). For Tuten, Mao Zedong and the Red Army are clear, if not unambiguous, heroes.

In this respect, Mao is a document of that fleeting historical moment when Mao and the Chinese Cultural Revolution symbolized the insurrectionary desires of Western youth. The breadth of Mao’s historical imagination intensifies rather than diminishes this identification: passages from Whitman and De Forest on the American Civil War, as well as from London’s socialist sci-fi The Iron Heel, urge us to consider the far-flung struggles of peasants of the Global South in sympathetic vibration with America’s own revolutionary struggles. Mao dissects this process of identification without ever repudiating it. It is, as Tuten put it, “an ironic work impervious to irony,” and in this precise sense we might say that Maohad the courage to be a symptom of its time (Frederic Tuten. “Twenty-Five Years After: The Adventures of Mao on the Long March” . Archipeligo. Vol. 1. No. 1. ).Mao is evidence that whatever chain of misunderstandings led American youth to identify with the Red Guards, what counted was the world-historic unleashing of transformative energy that this imaginary alliance made possible.

A speaker begins reading and immediately you know that she is a poet, and she reads the text as if it were poetry. Next, a young man with hair the color of his politics—fire-truck red. As his passage begins, the words of the previous hang in the air, crackling and insistent. Page 21, Fragment 18: “Three thousand enemy troops joined the Red ranks!” The crowd goes wild. Many in the room have waited their whole life to cheer words like these. Next, a man the left side of whose face is paralyzed. English is not his first language. He strains to speak, as does the audience to listen, and a hush falls over the crowd as he solemnly delivers the bad news: Page 31, Fragment 24: “The Communists did not get through… one third of the force was destroyed.” Booo! A professional actor dies on stage trying to make the twenty-page excerpt from Engels entertaining. An intern reads Mao’s proclamations of love to his wife like her own diary. Every reader contributes something of themselves, even if it is only the palpable sense that they do not want to speak the horrors of war. The only way to cross that river in a machine-gun barrage is to read each word in succession and turn the page.

Now it is your turn. You must read the passage. Haltingly, because you do not know the words that you are speaking. With doubts, because though many of the words are familiar to you, when you try to give them voice you question your pronunciation, and your conviction. But as the words accrete and take shape over five minutes, twenty minutes, an hour, you begin to speak them with a confidence that is yours, though it comes from another place. The same incantations pass through the pen of Oscar Wilde, through the lips of Tuten’s Mao, through the pen of Mao’s Tuten, through your lips all at the very same time.

Immediately championed by Susan Sontag, Harry Mathews, and John Updike when it first appeared, Mao marked a rupture between the straightforward American narratives of the early part of the postwar era and the more ambitious literature that followed. Before Tuten, a social novel would mean something likeSister Carrie or Babbitt, but afterward it was anything from Robert Coover’s The Public Burning to the school of minimalist realism championed by Gordon Lish.

Tuten continued the work he began in Mao with a loose trilogy of avant-garde adventure novels—Tallien, Tintin in the New World, Van Gogh’s Bad Café—where the figures of life journey farther and farther into their self-sufficient fictions, a maze of signs and dangling philosophies, ultimately becoming independent of their creators. Alternately as ingenuous as his Tintin and as cunning as his Mao, Tuten has remained a nomad of the cultural landscape, too restless, as Paul La Farge put it, “to stay put in the drafty château of the domestic novel, or any 19th-century literary form; he has to move around, to look for a new story to tell” (Paul La Farge, “The New World, or, How Frederic Tuten Discovered a Continent”. The Believer, May, 2005).

Today the aesthetic strategies of Mao are ubiquitous and have been technologically radicalized, both for better and for worse. In the age of the mashup, everything is stolen, and piecemeal is the main course. Masscult-midcult divisions have become irreversibly bridged and the path to art leads through a bramble of ambisexual pulp icons, digital rock-and-roll stars and fake news. Even as digital technology democratizes access to the means of artistic production, it distorts space and time, fact and fiction, and converts all things into the currency of the image. Personalized marketing threatens the role of criticism and community, leaving readers to languish in computer-generated solipsism as product-recommendation algorithms dictate to them their demographically-determined tastes.

Mao was a harbinger of this postmodern future but is also its remedy. Against the age of enforced hedonism, Mao affirms the arduousness of artistic and political struggle and the superior value of pleasures harder won. Against the false democracy of consumer-created content, Mao affirms the communization of culture. Against the neutralizing instantaneity of digital consumerism and electoral polling, Mao affirms that which is eternally new. On December 4, we invite you to join us in this affirmation.

We read for over four hours that October day. When we came to the end of the words, we realized that we had not come to the end of the book. At that moment, thousands were gathering in demonstration in Times Square. It had become impossible not to join them. A short time later, when we stood in the square bathed in cascades of Coca-Cola and CNN-flavored light, we knew we were not alone—and that reading itself is never a solitary act. Wresting the Chairman from the pages of a novel, we hoist his banner aloft for our own movement. And from there we took to the streets chanting, “Whose time? Our time!” Now is the perfect time. Youth are on the streets. The march of freedom again shakes the earth. Why try to keep a sure footing when you could dance?

-The New Inquiry

Patrick Harrison edits If You Can Read This You’re Lying

JW McCormack is a senior editor at Conjunctions

Andrew Starner is a PhD candidate in Theater Arts and Performance Studies at Brown University

Sherry Mills is an artist and photographer based in New York.