Those who are truly contemporary, who truly belong to their time, are those who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. They are thus in this sense irrelevant. But precisely because of this condition, precisely through this disconnection and this anachronism, they are more capable than others of perceiving and grasping their own time.?

—Giorgio Agamben,

from “What is the Contemporary”

Why is poetry #trending in contemporary art?

POETRY is having a moment. Pasted on walls, crammed into press releases, and crawling across your screen, the word poetry seems to be everywhere lately. At MOCA and MoMA, at the New Museum and the Whitney, in commercial galleries, performance spaces, and underground venues you’re likely to find grand invocations of a literary form few people actually read. The combination is a strange one. The art world is restless and poetry slow; the art world is rich and poetry laughably poor; there must be a catch. In these contemporary art spaces, poetry has appeared in many guises: as object, installation, conceptual exercise, artist book, press release, digital experience, performance, and inter-relational happening. Yet, if you relied on press releases and wall text alone, it would seem as if each show’s version of poetic art or artsy poesy were new and groundbreaking, when in truth, most contemporary artists and curators have been recycling the same material.

So why then is poetry #trending? As the Pil and Galia Kollectiv point out in the e-flux symposium, “On Claims of Radicality in Contemporary Art,” galleries and big institutions are “frantically searching” for “credible artists, like a colonial arms race to find the last remaining unexploited continent.” Perhaps poetry is that last continent. Its apparent lack of market value lends it anticommercial credibility that is readily exploitable. It offers artists and curators a mode of communication that seems the opposite of artspeak SEO because it has no instrumental value. Amidst an atmosphere of commercial frenzy, historical amnesia, and geographic myopia, I’ve attempted a kind of critical survey of the contemporary scene, and hope to highlight other thinkers who are doing the same. This is an effort to connect the dots, to ask: why poetry — why now?

DRY GOODS

It is not difficult to imagine a painting as a poem. Museumgoers have become accustomed to letters on canvas since the turn of the 20th century, from Picasso to Marienetti to Broodthaers, so the leap from the page to the gallery wall is a relatively easy one. In 2011, MoMA curator Laura Hoptman brought together a show entitled “Ecstatic Alphabets/Heaps of Language,” drawing on MoMA’s vast permanent collection and assembling 12 contemporary artists and artist groups to “represent a radical updating of the possibilities inherent in the relationship between art and language.”

Unlike the other shows I plan to discuss, this one included equal parts contemporary and historical work. The tropes, gestures, and preoccupations represented in “Ecstatic Alphabets” are the basis of so much of the current “poetic” work appearing today, but because critics and curators operate in the paradigm of contemporary art, they have to find a way to demarcate the work earlier iterations. Even if we’ve abandoned progress, we’re still attached to novelty.

In his review of “Ecstatic Alphabets” for Artforum, Tim Griffin attempts to find a fissure between the old intersection of contemporary art and poetry and the new one, tracing a shift in emphasis:

If artworks from earlier times here suggested an ordering of space effectively being unlocked by language, such more recent pieces then suggested how language is always imbricated in social context and inevitably gives rise to kinds of signification — and, further, the possibility to write in space anew.

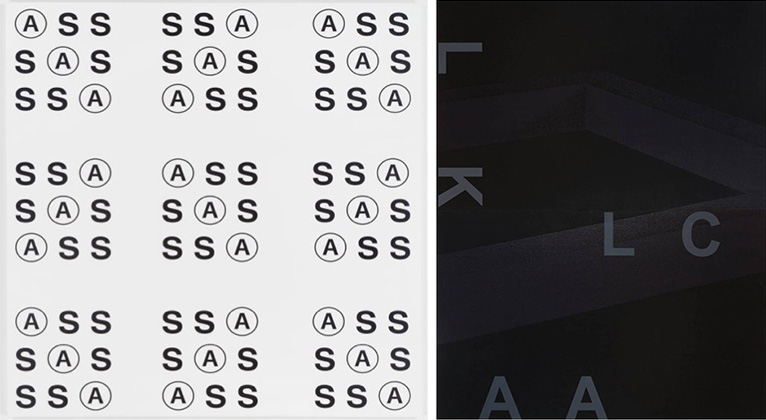

As Griffin sees it, the first wave in “Ecstatic Alphabets” is mostly concerned with the conceptual structures of language and its spatial arrangement or dissolution, while the next batch is going beyond materiality to a consideration of power relations from which the work emerged. Two artists from the show, Karl Holmqvist (b 1964) and Adam Pendleton (b 1984), appear to diverge along Griffin’s lines. According to Hoptman, Holmqvist “dimensionalizes his poems very much in the way of the Concrete poets 60 years ago.” He combines text cribbed from pop-cultural icons like Beyoncé with advertising flotsam and the language of the everyday — sometimes in mad all-caps scrawl — and collages it onto paintings or wallpaper pasted to gallery floors. Repetition and sophomoric language games abound, as in the scrambled grid of “BIG ASS PAINTING.”

Following Griffin’s analysis, what distinguishes a younger artist like Pendleton is not so much the operations he uses but the ends to which he puts them. Pendleton’s phrases are explicitly political, or art-historical, or borrowed from African-American writers and thinkers. His word choices creates strong associations, but don’t seem to denote much, as in the wall-size installation, “Notes on Black Dada Nihilismus (proper nouns),” from 2009:

?MONDRIAN JESUS HERMES

TRISMEGISTUS MOCTEZUMA

WEST SARTRE GERMAN GOD

TAMBO WILLIE BEST DUBOIS

PATRICE MANTAN JACK

The problem with billing these word-heavy works as poetry is that they are not poems — at least not good ones. They are objects first, and texts second. Many of the works in “Ecstatic Alphabet” fragment language to create a glossy but opaque linguistic surface — just so much visual matter. In her curatorial statement for the show, Hoptman writes that poetry “runs like a subtheme through the exhibition, adding the ecstatic element to each works’ alphabetic plainness.” Yet that ecstatic element remains ill-defined, a numinous window dressing.

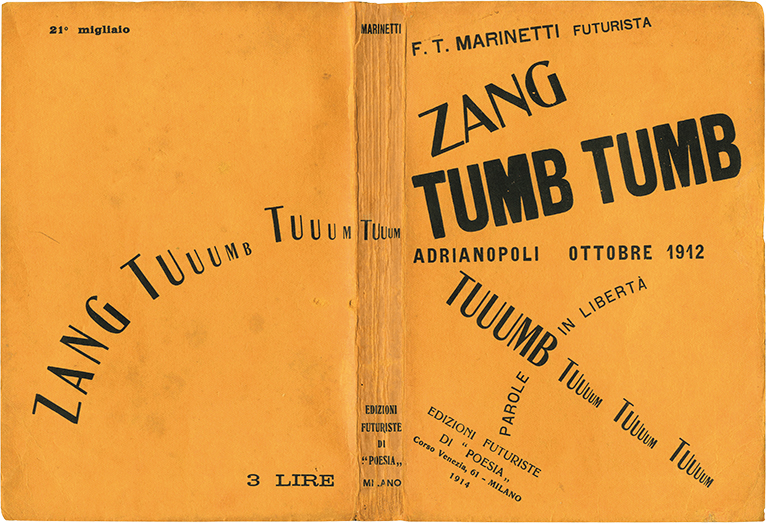

The most interesting pieces in the show resist the concretizing impulse (John Giorno’s 1970 “Dial A Poem”) or attempt Fluxist strategies of diffusion, as in Dexter Sinister’s $5 exhibition catalog. Works initially intended to circulate freely, like Lennon and Ono’s “War is Over” poster, were instead riffed on and rarified, as in Experimental Jetset’s 2003 “Zang! Tumb Btumb, (If You Want It),” which was tacked to the wall in a group of six and later bought for MoMA’s permanent collection. Holmqvist shows at Gavin Brown, while Pendleton is represented by Pace. In short, much of the poetic art included “Ecstatic Alphabets,” new or old, aims to sell, which runs counter to poetry’s essential properties of immateriality and worthlessness.

CONCEPT

Until a few months ago, contemporary avant-garde poetry was dominated by a group of writers dubbed “conceptualists.” The poetry that came out of this movement may have seemed about fifty years behind the art world, but to many lyric poets, the disruptive agenda of conceptualism was a cold and unfeeling heresy. For decades, MFA programs have been churning out well-wrought urns of prosaic confessionalism, catalogues of bodily function, and sincere paeans to departed family members. The speaker will be washing the dishes when suddenly transported to a dusty country road and a childhood memory of Grandma. This is a generalization, but not a gross one. Billy Collins and Natasha Trethaway were recent U.S. poet laureates.

Opposed to all these feelings, poets like Vanessa Place and Kenneth Goldsmith made their careers by dismantling the notion of a poem having a speaker, a voice, or even an author. This type of appropriative work was positioned as a departure from earlier found-text poets like Charles Reznikoff or William Burroughs, because the poetry proceeds from an idea, as in Goldsmith’s The Weather, Traffic, and Day, or Place’s lengthy, unaltered domestic-abuse transcriptions in her trilogy, Tragodía. The poem is secondary to the idea, merely execution.

Like their antecedents in the fine art world, Place and Goldsmith use appropriation to simultaneously elevate and equate the banal and the grotesque — either through cunning selection, or by relying on sheer volume to overwhelm readers with the immensity of their archives. But because their works have been primarily published as books rather than as paintings, conceptualist poets were able to operate under the rubric of literature and thereby claim that their enterprise was new.

The poetry community accused them of laziness, insensitivity, and provocation. The art world was more receptive. Their hijinks could be assimilated to the moves of 1960s conceptual artists like Sol LeWitt or Ed Ruscha, but with the added media savvy of a David Salle. The feelings their work provokes, too, are akin to the alienation and discomfort one experiences when viewing a something like “Workers Paid to Remain Inside Boxes” by Santiago Sierra. In 2013, Goldsmith launched his self-explanatory gallery project, “Printing Out the Internet” and became the first poet laureate of MoMA, while Place has performed at London's Whitechapel Gallery and the 2012 Whitney Biennial, among many others.

Majorie Perloff, a critic and defender of Place and Goldsmith’s, invokes John Cage to claim that avant-garde poetry is not interested in feeling or voice and certainly doesn’t take them as the defining features of the form. Through Cage, she writes, “Poetry is not poetry, as he put it, ‘by reason of its content or ambiguity but by reason of its allowing musical elements (time, sound) to be introduced into the world of words.’”

Of course, all poetry is attuned to time and sound. Poetry is merely aestheticized language. The aim of conceptualists like Place and Goldsmith is to expand that world of time and sound to encompass all kinds of other texts, much like Duchamp wanted to expand the world of sculpture to urinals. The problem they face is how to keep their choices interesting.

Conceptual poetry’s cozy association with museums came apart in March of 2015, when Kenneth Goldsmith read aloud the autopsy report of Michael Brown at Brown University’s Interrupt, a gesture widely regarded as sensationalist and racist exploitation. On Facebook, he subsequently attempted to frame the piece as part of his larger, Warholian Seven American Deaths and Disasters series but failed to explain why he made the choices he did (ending with a description of Brown’s genitals, for instance) other than “to make the text more literary.” Place met a similar fate for tweeting the entirety of Gone With the Wind, ultimately prompting groups like The Mongrel Coalition to accuse her of racism and white supremacist appropriation. Place has since been disinvited from AWP. Goldsmith has gone into self-imposed exile.

PERFORMANCE

Perhaps seeking to avoid the taint of conceptualism, contemporary art institutions are choosing to present poetry as performance. At MOCA, in Los Angeles, senior curator Bennett Simpson has begun inviting poets like Claudia Rankine and Maggie Nelson to participate in a monthly reading series. “I wouldn’t say I curate poetry,” Simpson told me. “I think that’s blurring things in a way that’s unnecessary. I’d say that I organize readings. Maybe that dates me.”

As Simpson sees it, the aims and effects of this kind of programming are straightforward. Poets appear on a stage and read to an audience. The readings plug into the same format as musical performances, lectures, and other voice-based durational events. Hopefully the readings play against the architecture and the work on display.

At the same time, hanging behind the windows of MOCA’s storefront space is a separate cross-contamination of poetry and art, an installation of two poems by Nathaniel Mackey as part of a collaboration with Public Fiction: “Song of the Andoumboulou: 148” and “Sweet Safronia’s Wave Unwoven.” The show, curated by Lauren Mackler combines an installation, reading, film series, live online platform, and a physical publication. This multimedia extravaganza directly — rather than obliquely — puts poetry into conversation with other art forms and uses the figure of the poet as a theme for the show. Mackler even makes a point of commissioning the poetry in advance and paying poets the same honorarium as any other participant. “I consider it a really important political act to pay the people for their intellectual exercise,” says Mackler. “Not just for whatever capital they produce that can be turned into more capital.”

MOCA is also bringing in younger poets such as Kate Durbin, Juliana Huxtable, Trisha Low, and Felix Bernstein as part of their annual performance series, Step and Repeat — the same loosely affiliated millennial crowd whose work has been popping up at the New Museum, the Whitney, and in other major art spaces. This crop has been explicit about positioning their poetry as performance. Huxtable, whose work and visage were featured in the 2015 New Museum Triennial, began her career as a nightlife impresario, DJ, and performance artist. Kate Durbin and Trisha Low both blend visual spectacle into their readings, with elaborate costumes, glitter, and the occasional spurt of fake blood. Bernstein has perhaps gone further than the others, adapting a section of his 2015 poetry collection Burn Book into a full-scale production for the Whitney Museum’s new performance space, entitled “Bieber Bathos Elegy.” Imbued with the improvisational schtick of vaudeville and the alienating creepiness of Klaus Nomi, the opera, despite rough patches, was studded with memorable moments, with a super-size Bieber alternately seducing and rejecting an overwrought Bernstein.

Bieber

… you fag

queer devotion

is dull

all perversion is performance

all performance is banal.

suck my dick, you suck,

suck my dick, faggit

FB

NO, let me be impure, take me far from here

On the page, it doesn’t hold up as well as did in the Whitney. Bernstein’s play with repetition and his delight in switching between theoretical and vulgar registers keeps the piece afloat, but it lacks the force and inventiveness of less formally constrained sections of Burn Book, from which it is adapted. In playing with the boundary of poetry and opera, Bieber really just reads as a libretto, as a kind of shadow or diagram of a performance.

Because of their willingness to experiment and resist categorization, Bernstein and poet-performers like him are more unpredictable than materialists or conceptualists. You don’t know what to expect when they call something “a poetry reading.” “There is still a radical potential with performance,” says Jay Sanders, curator of performance at the Whitney, “to surprise, challenge, and even disrupt our expectations for how art can shape our experiences.”

POST-INTERNET

If conceptualism tried to erase the need for an author, much of post-internet poetry transforms that author into a social media manager, moving the poem from the page or the stage to a tweet, status update, Amazon review, sext, or YouTube confession. Identity, surveillance, Photoshop, social media, and bright colors converge to create an aesthetic that doesn’t just mirror the tropes and values of the internet — it buys into them.

Poetry was integral to the 2015 New Museum Triennial, “Surround Audience,” curated by Lauren Cornell and artist Ryan Trecartin. The New Museum released a poetry anthology to accompany it, The Animated Reader: Poetry of Surround Audience, edited by Brian Droitcour. The poems in The Animated Reader and featured on the walls of the museum vary significantly. Some are by prominent poets, like Mónica de la Torre and Roman Osminkin, others appear to have been included because they imitate the textual field of the internet: the surplus of information, the oscillation between hyperbole and lethargy, the endless buzzword-laden performances of self. The poetic epiphany amid the language of the everyday.

These preoccupations are not inherently tiresome but their ubiquity and repetition in the writings of Trecartin and Durbin (whose work is in the show’s catalogue) makes them so. Melissa Broder, of So Sad Today fame, ends her poem “ALONG" (hosted on the New Museum’s site “Poetry as Practice”) with the couplet “How does it feel with your body gone / Narcissus weeping but the stars like yeah.” It’s all there: the mind/body internet/IRL thematics, the final line deflating itself with a bored shrug. This coterie of poets doesn’t critically engage the conditions of digital life; they just point to them as a means of syphoning off the cachet of critique.

In an essay Droitcour wrote for Art in America three years before he edited The Animated Reader, entitled “The Perils of Post-Internet Art,” he calls much of the art in this nascent movement “boring to be around.” Unfortunately, the same can be said of many of the so-called “surreal or poetic statements” included alongside more ambitious poems in “Surround Audience” and The Animated Reader. As Quinn Latimer writes in “Art Hearts Poetry,” much of this work simply apes “the new linguistic currency of the internet: advertorial, adolescent, content-driven, anxiety-ridden, always appeasing, liking, performing, sharing, driving the shares up.”

Successful post-internet poems should not merely “update confessional poetry for the age of mass surveillance,” as Droitcour advocates in his opening essay for The Animated Reader. Poems that want to mirror or deconstruct the experience of living on the internet need a poetics that address that experience on a structural and material rather than semantic level. Poets like Tan Lin, whose work is often displayed on a screen rather than a page (and and whose poems are also included in “Poetry as Practice”), adopts what he calls an “ambient stylistics.” It’s a poetics that refuses to let the reader concentrate; instead of presenting a static poem, Lin makes his words flash, fade, and wiggle. His texts are set against colored backgrounds, and as in “Dub Version,” sometimes move so slowly that few viewers would bother to or be able to hold the piece together in their minds. In “Eleven Minute Painting,” Lin uses a slightly broken, female computer voice to recite his poem as it appears on the screen. The inhuman speech patterns transform what might be a brittle text into a strange and eerie ars poetica. “It would be nice to create works of literature that didn’t have to be read,” says the voice. “But could be looked at like placemats.”

To my mind, the most interesting convergences of contemporary art and poetry do not occur when the art world dips into poetry but when poets like Lin, Bernstein, Low, Mackey, and others take up the techniques of artists, making work that succeeds as poetry and that can be disseminated as text rather than as rare art object. Publishing initiatives like Primary Information are reviving Fluxist strategies by putting out facsimiles of rare and hard to find artist books, eschewing “collectors who are dominating so many other parts of the art world,” as co-publisher Miriam Katz explains in an interview with Bomb. Their model corrects the art world’s fetishized scarcity. “I don't think that books are meant to sit on somebody's coffee table and never be read,” says Katz. “I think that they're meant to be consumed and lent to other people.”

It’s unclear to me how much longer the art world will care about poetry. It may soon go the way of performance or dance and fade into the shadows of the contemporary art scene, only to be rediscovered in twenty years. If this relationship is to continue, I hope poets will keep a few things in mind.

“There is now a vast amount of artistic production that is temporal, discursive and post-object centered,” writes John Roberts in Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde. And this immaterial work is “identified explicitly with a whole range of non-artistic skills and activities (scientist, ethnographer, anthropologist archivist, teacher, engineer, activist).” If we agree with Roberts’s assertion that the avant-garde is moving toward practices that don’t look much like art, then poets are uniquely positioned to participate. If avant-garde artists are trying to dematerialize their work, then poets have already done it. If the avant-garde artists want to disseminate their work freely or cheaply and outside the gallery system, poets have been doing this with self-publishing and small presses for a very long time.

The question becomes: What kind of poetry will these fine art institutions embrace? Will poetry just act as a mask for fuzzy curatorial logic? Will the poetry presented in contemporary art institutions have to be contemporary itself, and will its inclusion canonize only those poets with art-world access?

Poets have the potential to make critique in a way few fine artists do — without having to couch their language in abstraction, or to convey their ideas in gesture or material. As long as they barely pay us we have little to lose. To go the way of the Bernadette Corporation and attempt to make poetry more commodified, more in line with contemporary art’s market logic and formalist preoccupations is a mistake. Poetry’s slowness, difficulty, irrelevance — these qualities must be made into virtues. If we circle back to Agamben, poets who are out of step with the time are the most contemporary of all.

Perhaps I am asking too much of poets — but when I read the work of people like CA Conrad, I regain a modicum of hope. Conrad’s work intrigues me because it is both processual and product-oriented, involving a series of elaborate instructions for the creation of poems, which he calls “rituals.” They’re theoretical exercises, but they have far more warmth and generosity of spirit than the conceptualism of Place and Goldsmith. The (Soma)tic rituals are like Yoko Ono’s instructions for performances in that they are poems in and of themselves, but they also posit a relationship that circumvents the usual author/text/reader triad, and they glimmer with possibility. Their purpose is to invite the reader to create poems of their own, and to invent their own rituals for generating new poems. Conrad writes:

A poet and a painter deposit letters for one another inside newspaper boxes on opposite sides of a street. We wave to each other, then begin reading the letters, which explain the ways we would like to die. Found in the morning on the floor of a boat after being impaled in the chest by a swordfish while night fishing. Or fragment of my bloody shirt found after having sex with lions. We read our letters, then begin writing or painting in view of each other. An hour later, we meet in the middle of the street to embrace and dance the foxtrot, with the painter leading, then switching to the poet leading. We return to writing and painting within view of each other.