The most magical innovation of the app economy is making the female workers it depends on mostly invisible.

Andrew Norman Wilson was fired from his contracting job at Google for interacting with what he called a different “class of workers.” He had been watching them for months as they exited the office building adjacent to his. Everyday they left at 2 PM (he later learned that their shifts began at 4 AM). “They were purposefully kept separate. They carried yellow badges that restricted access everywhere besides their own building,” Wilson said.

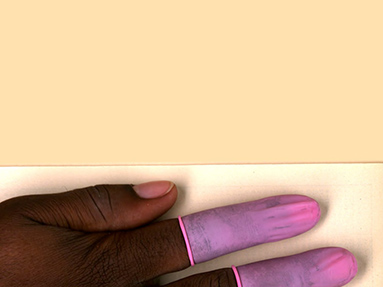

They were mostly black and Latino—a rare sight on Google’s predominantly white campus. They worked for ScanOps, the team that did the painstaking work of scanning texts that make up Google Books. Intrigued, Wilson attempted to interview some of them. He managed to get a few minutes of tape before he was caught by Google security. He was fired shortly thereafter.

Of course books don’t digitize themselves. Human hands have to individually scan the books, to open the covers and flip the pages. But when Google promotes its project—a database of “millions of books from libraries and publishers worldwide”—they put the technology, the search function and the expansive virtual library in the forefront. The laborers are erased from the narrative, even as we experience their work firsthand when we look at Google Books.

There is a tradition of humans posing as machines called “mechanical turking.” The tradition is named after the “Automaton Chess-player.” Unveiled in Austria in 1770, the automaton appeared to be a robot dressed in Orientalist clothing (hence the “turk”). But in reality, a human being hid inside the machine and moved the chess pieces with magnets. The best chess masters of the time crouched beneath that chessboard.

Much like the man who jams a chess grandmaster into a dark cage in order to be celebrated for "inventing" the cage, Amazon has built a massive network of casualized internet laborers whose hidden work helps programmers and technological innovators appear brilliant. Their Mechanical Turk program, taking its name from the 18th century curiosity, hires people to do invisible work online—work which makes their client companies’ software look flawless. Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos calls it “artificial artificial intelligence.”

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is a marketplace that allows companies to post jobs that anyone can sign up to complete. These are tasks that come easily to people but are hard to program a computer to perform: accurately transcribing text from audio, detecting the quality or tone in a piece of writing, identifying what’s depicted in a photograph. Amazon refers to these as Human Intelligence Tasks. Ninety percent of human intelligence tasks pay under $0.10 per task.

Such “crowdworking” exists in a legal gray area. While workers are required to report their income for taxes, employers are not required to pay payroll taxes, overtime compensation, or honor minimum wage. The New York Times reports that workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk earn an estimated range of $1.20 to $5 per hour on average. Even more controversially, the terms of service allow employers to “accept” or “reject” the work after they receive it, no questions asked. The company is allowed to keep the work after they “reject” it, but the worker is denied pay and receives a lower online rating, making it harder to obtain future work on the site.

But the legal structure of Mechanical Turk is such that Amazon can pretend this incredible imbalance isn’t their fault. As the company is only a "marketplace", Amazon claims that it’s “not responsible for the actions of any Requester,” since they’re only providing “the capacity of a payment processor in facilitating the transactions between Requesters and Providers.”

Tech entrepreneurs are well aware of the asymmetrical power dynamic this situation creates. “Before the Internet, it would be really difficult to find someone, sit them down for ten minutes and get them to work for you, and then fire them after those ten minutes. But with technology, you can actually find them, pay them the tiny amount of money, and then get rid of them when you don’t need them anymore,” Lukas Biewald, CEO of the site CrowdFlower, was quoted as saying in The Nation.

The contract workforce keeps much of Silicon Valley running. New York Magazine reported that companies like Lyft, Uber, Homejoy, Handy, Postmates, Spoonrocket, TaskRabbit, DoorDash, and Washio all classify their workers as independent contractors rather than employees. This has massive financial benefits for the companies: allowing them to forego benefits and minimum wages, to say nothing of pensions or unemployment insurance, while forcing employees to pay for necessary business expenses (e.g the Uber driver’s car). It also has huge legal advantages: by claiming they are just a “marketplace,” the services can deny all legal responsibility for the behavior of their contractor-employees, letting them ignore labor and safety regulations, and potentially saving them millions in individual liability lawsuits.

But, crucially, these apps don’t flourish because of low prices—these “savings” on the part of the start-ups typically don’t go to customers in the form of dramatically lowering costs. Instead, the appeal of apps like Uber is that anyone with a smartphone can press a button and a driver shows up. Press a button and lunch is ready, flowers are sent out, laundry gets done, the house is cleaned. It’s like magic.

It is precisely the feeling of magic—the instant gratification of desire being met the very moment it’s felt—on which the apps market themselves. The entire discourse surrounding the app economy centers on the thrilling ease achieved by high tech efficiency: it’s this magic that the apps sell, the thing that differentiates them from traditional modes of purchase. Because otherwise the consumer is just getting a cab ride, just buying groceries, just hiring a housecleaner.

It’s like magic, but it’s not magic. The magic is founded on grossly underpaid, casualized labor. Press a button and a human being is dispatched to do menial work. Press a button and an independent contractor, without the same rights and protections as an employee, springs into action. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is merely the most literal and obvious manifestation of this trend. The actual magic trick is making the worker disappear.

Who exactly are these disappearing workers? And if they are the same workers who historically have performed invisible, unappreciated work, what does it mean about the “innovation” of the app economy?

It’s very hard to get accurate statistics on the contingent workforce in the tech industry, as tech companies are less than forthcoming. But researching the demographics of mechanical turkers is even harder, as they are decentralized and anonymous. In 2010, New York University professor Panos Ipeirotis conducted a rare study to assess Amazon’s Mechanical Turk workforce. Ipeirotis discovered that almost half of the work force is American. (In fact, the percentage of Americans on the site has significantly increased since Ipeirotis’ study. Amazon changed its terms of service, requiring identity verification of its turkers, which ruled out many Indian workers who could not provide proper forms.) This upends a common argument used by the company’s defenders, who claim that $0.10 a task or $1.20 an hour goes a long way in countries like Pakistan and India.

But would workers be better off without the site? This was the question Ipeirotis leveled to me when I asked him about the mechanical turkers’ low wages and lack of power. People were on the site “voluntarily”—as much as capitalism allows anyone to work “voluntarily.” Workers on the site were free to leave. Workers on the site tended to be American. They tended to be young. Many were caregivers of young children or the elderly and so it benefited them to work from home. And they tended to be women.

Ipeirotis found that almost 70% of mechanical turkers were women. How shocking: the low prestige, invisible, poorly paid jobs on the internet are filled by women. Women provide the behind the scenes labor that is mystified as the work of computers, unglamorous work transformed into apparent algorithmic perfection.

In fact, beyond simply doing work that computers cannot do, mechanical turkers actually improve computers. When a turker works on a project, she creates a data set which the computer can then learn from. “Computers document the signals generated by humans. They can use this data to start learning. Computer algorithms get generated by data created by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers,” said Ipeirotis.

Relying on data from mechanical turkers, computers have dramatically improved in recent years at facial recognition, translation, and transcription. These were tasks previously thought to be impossible for computers to complete accurately. Which means that mechanical turkers (mostly women) teach computers to do what engineers (mostly men)

Female mechanical turkers meet their parallel in the female computers before them. Before the word “computer” came to describe a machine, it was a job title. David Skinner wrote in The New Atlantis, “computing was thought of as women’s work and computers were assumed to be female.” Female mathematicians embraced computing jobs as an alternative to teaching, and they were often hired in place of men because they commanded a fraction of the wages of a man with a similar education.

Though Ada Lovelace is finally getting some notice almost two hundred years after she wrote the first ever computer algorithm, the women who have advanced math and computer science have largely been ignored. When male scientists from University of Pennsylvania invented the Electronic and Numerical Integrator and Computer, the first electronic computer (which would eventually replace female computers), women debugged the machine and programmed it. When these early female computer programmers unveiled the machine to the military, they were mistaken for models hired to stand attractively next to the new invention.

As computing machines gradually took over, mathematicians often measured its computing time in “girl-hours” and computing power in “kilo-girls.” The computer itself is a feminized item. The history of the computer is the history of unappreciated female labor hidden behind “technology,” a screen (a literal screen) erected by boy geniuses.

Silicon Valley really is a man’s world. Men have great ideas. Men code. Men attract money. Men fund start-ups. Men generate jobs. Men hire other men. Men are the next Steve Jobses, the innovators, the inventors, the disruptors. But women complete the tasks that men have not yet programmed computers to do, the tasks that make their “genius” and their “innovation” possible. And they do it for pennies.

Comments are closed.