He was funny sometimes, maybe most of the time, but nobody could be funny all of the time. And being funny was sometimes a way of being dishonest.

—Sherman Alexie, “What Ever Happened to Frank Snake Church?”

There are few people, and even fewer Indians, as widely loved in the literary world as Sherman Alexie. He is perhaps the closest thing to a rock star that Indians have. Not only is he an award-winning, best-selling author, but he became one by writing about drunk, despairing, poor Indians based on his own experiences living on the Spokane reservation. And most important, he writes about them with charm and wit rather than the doom and gloom of Dee Brown and Diane Sawyer.

Usually when Indians make prime time it’s in a parade of dire statistics about poverty, alcoholism, and suicide on reservations. In his stories, Alexie does not directly challenge this image of a broken people naturally prone to self-destruction and struggling to survive in the modern world, but he writes about the child abuse, alcoholic fathers, and dead-end lives in tones light and breezy. He says when an Indian dies of alcoholism it should be considered “natural causes,” and he says it so you laugh.

That line, a flippant address to the very unnatural death by destitution common in Indian populations, appears multiple times in the latest collection of Alexie stories, Blasphemy. Every zinger Alexie writes must be written at least twice, so this career-spanning collection of new and selected shorts is full of one-liners stretched beyond their means. Just a shade away from cliché to begin with, Alexie’s language becomes a parody of itself. Blasphemy is a repetitive catalog of ways in which Alexie has made comedy from tragedy. The stories are mostly in the first person, mostly involve men, who mostly talk in the exact same way, and who are struggling with one or all of the following problems: women, fear of death, and absent fathers. They are almost all “funny.”

Despite cycling and recycling the same old tropes told in the same voice, Blasphemy has received not one poor review. Is Alexie really such a flawless writer that critics cannot go beyond praise as repetitive as his oeuvre itself? Or are most reviewers seduced by the charming prose of an Indian who eases their guilty consciences? The latter seems much more likely.

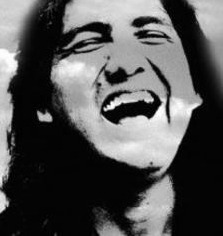

In a wonderful triumph of multiculturalism, Alexie can get famous writing about one of the most brutally repressed people in and because of America—just as long as he supports the popular perception of Indians and is friendly enough to have a good laugh about it. The laughter is key. Angry Indians do not win National Book Awards very often unless their anger is masked in metaphor, contained in the beautiful intricate prose of a Louise Erdrich or, in the case of Alexie, delivered with a punchline. Not only are his stories shot through with humor, almost every image of Alexie shows him laughing. On the cover of Blasphemy, in his twitter avatar, in the first images of a Google search: the guy is almost always buckled over in laughter.

In his classic work, Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, Vine Deloria Jr. bemoans the persistent image of the “granite-faced grunting redskin.” Deloria, who dedicates a whole chapter on “Indian Humor” to disproving this stereotype, might have praised Alexie for popularizing an image of Indians that shows them to be light-hearted and comical.

But Deloria also prized Indian jokes for their critical presentation of white society and the brief but exuberant resistance to white power over Indian lives. Alexie usually makes fun of Indians rather than white people, his critiques of white society are buried beneath the jokes that make him famous. These occasional outbursts are just enough to give him edge, but they never cross the line into threatening.

Through his use of comedy, Alexie has drifted from one stereotype to another. He has traded the cigar-store Chief for the Cleveland Redskin smiling his offensively goofy grin. To be fair, Alexie’s characters are astronomically more emotionally complex than either of those stereotypes allow Indians to be. But in whole, just as Alexie is in his own public image, these men are presented as laughing Indians. They may be broken, haunted men, but they are jesters.

This laughing Indian is little better than the laughed-at Indian. Stoic or not, Indians have always been laughed at. Iron Eyes Cody, that Indian played by an Italian with his big fat tear over litter, is an instant visual punchline. Cartoons especially present the stoic Indian as absurd. In Peter Pan the Indian chief is angry and very stern, but instead of his rough nature making him threatening to white children, it makes him silly. Whether stone-faced or grinning, the Indian must not be taken too seriously.

Continuing in the tradition of the Indian buffoon is the Alexian hero. These are Indian men who are emotionally immature and unable to face reality. They are motor mouths with a joke for every occasion, but enough pathos to be truly endearing. The best thing we can say about their subversion of Indian stereotypes is that they are not silent. Typically the silence of the stoic Indian has made him all the more susceptible to mockery; the Alexian hero does that work himself by being both the maker and center of the jokes. Alexie’s characters may be more rounded than the angular frozen cartoons, but they are nearly as infantile. The women of these stories, decidedly not as funny as the men, are their caretakers and without them they falter.

The story “The Approximate Size of My Favorite Tumor,” is classic Alexie and thus a good character study of the Laughing Indian. Against a rez backdrop of HUD housing and honky-tonk bars, it tells the tale of a struggling marriage between a goofy Indian with terminal cancer, Jimmy, and his beautiful, wild Indian wife, Norma. We enter the story just as Norma is leaving Jimmy after threatening to do so if he told one more joke about the disease eating him alive. From here, Jimmy guides the reader zippily through a series of meandering memories and observations charting the formative moments in the relationship, from the moment they met in the Powwow Tavern to the time the cop pulled them over for driving while Indian. Eventually, the wild woman can’t resist the charm of the Alexian hero and returns to him in time for this sentimental and completely vapid conclusion:

“And maybe,” she said, “because making fry bread and helping people die are the last two things Indians are good at.”

“Well,” I said. “At least you’re good at one of them.”

And we laughed.

Despite all the trouble Indians have been through, they can still manage to love and laugh. Their stoicism, their ability to pretend at some kind of nobility, comes not from their seriousness but their wry laughter. Never mind that what Norma says makes very little sense. Sure, Indians are good at making frybread because they invented it, but what makes Indians good at helping people die? What is she even talking about? This seems like a perverted version of an Indian joke about white people only being good at helping people die...by killing them. But that kind of joke is much too severe to end a story—that might make the reader uncomfortable. Instead, Norma’s line concludes the story with the image of Indians making fry bread and dying. And “we laughed.”

The Alexian heroes’ immaturity causes them to lash out at serious, earnest, and more politically radical characters. “War Dances,” the eponymous story of an earlier Alexie collection, is again about a man who discovers tumors in his head. He however is struggling with Alexie plot number two: father issues. While the unnamed Indian guy—another funny man with pockets full of quips—confronts a scary disease, he is also preparing his alcoholic father for death. The story is told again through an assortment of observations, memories, riffs, all punctuated with punch lines.

In one particularly painful passage, the Indian guy pokes fun at a Sioux writer and scholar he recently heard calling for a movement of tribally-specific literature. He claims she is someone afflicted with “nostalgia” and describes her as a “charlatan,” akin to fraudulent medicine men. He pities her because she espouses a belief in “some kind of separate indigenous literature identity, which was ironic because she was speaking English to a room full of white professors.” In one fell swoop, the man rejects this woman’s ideology not on the basis of what she says but by trying to pin her as some kind of hypocrite for saying it. As if Indians can only talk to other Indians about Indigenous literature. When they dare to speak to white people, they are to be pitied.

The irony lies in knowing that the story comes from a man who must know his audience is filled with white people, and that Alexie chooses to speak to them in their language. It is in fact very telling that he would find ideas about the tribally-specific laughable—how would the award givers and nice liberals understand his writing if it was too Indian? In attempting to make his writing as palatable as possible, Alexie even deigns to annotate this bit of dialogue: “Ayyyyyy,” with the explanation, “another Indian idiom.” He is translating Indians for white people, making them not only more readable but more laughable.

Political Indians, Indians with ideas about tribal separatism, the Indians who pose the most threat to the legitimacy of the American nation, these are the Indians discredited and made fun of in Alexie’s stories. Even worse, in a morbid twist to the passage about the Sioux scholar, Alexie claims this woman’s nostalgia is “murdering her.” Alexie has this tendency to associate the Indianness white people find threatening with death, posing those who choose to distance themselves from radical Indians as the more relatable heroes.

His belittlement and derision of politically active Indians reaches its height in the story “Protest” which focuses on another Jimmy, a light-skinned Indian who becomes radicalized at Spokane Community College. Our protagonist believes the newly found fervor for justice arises from Jimmy’s paleness, noting that in many “pale warriors…their radicalism becomes inversely proportional to their skin color.” In trying to make fun of one lightskinned, politicized Indian, Alexie discounts a long line of very political, very brown Indians. In their place, Jimmy becomes the ridiculous stand-in, the buffoonish spokesperson for Indian resistance.

Jimmy is juxtaposed with Harold, a homeless Indian shot dead by police for carrying a three-inch carving knife. Though it seems for a moment that this story might present a critical view of state violence against Indians, it instead corroborates the kind of stereotypes that make such violence possible. In describing Harold, the narrator makes sure to point out that most of Harold’s tribe drank and “some drank themselves to death.” The narrator also describes Harold as having an angry face, one the police interpreted as threatening. So while the pale-skinned Indian buffoon makes a mockery of Indian protest, traditional Indians are either dying from being drunk or dying from being threatening. It is a story in which the dead Indian can be mourned (Americans have become very good at crying over dead Indians), political Indians can be discounted as fools, and the hero is the one making a joke.

In Deloria’s chapter on Indian humor, he praises joke-telling as the cornerstone of Indian political movements. He points out that the “fact of white invasion from which all tribes have suffered has created a common bond in relation to Columbus jokes that gives a solid feeling of unity and purpose to the tribes.” For both Deloria and Alexie, humor is about survival. The difference however is that Deloria sees survival in asserting tribal Indian identity, Alexie sees it in chuckling distance.

Alexie uses humor to make the tragic story of the Indian so desired by Americans even more appealing. It is not surprising then how Alexie could be deemed a “national treasure” in a country that hasn’t done much treasuring of Indians. As the laughing Indian, he renews a politically correct tradition of briefly addressing colonialism while never attempting to deconstruct or resist it. Meanwhile, more complex, challenging Indian authors like Gerlad Vizenor, Stephen Graham Jones, and Leslie Marmon Silko wither on the sidelines, acknowledged by a passionate few, while seeming excessive to the American reader who already has Alexie on the shelf. But these are the Indians who do not seek to please, they seek to unsettle.