True American exceptionalism doesn’t spring from the nation’s statehouses but from its garbage cans. The contemporary US is objectively extraordinary in that virtually anyone, including the extremely poor, can acquire collections of material goods of a volume unprecedented in human history. The consequences of this development have seeped through our thought and topsoil, but to visualize the significance of such expansive attainment, there is no better guide than those we are beckoned to look upon as misusers of this great power. We speak of hoarders, namely those featured in the award-winning and record-breaking A&E reality show of the same name, which began in 2009.

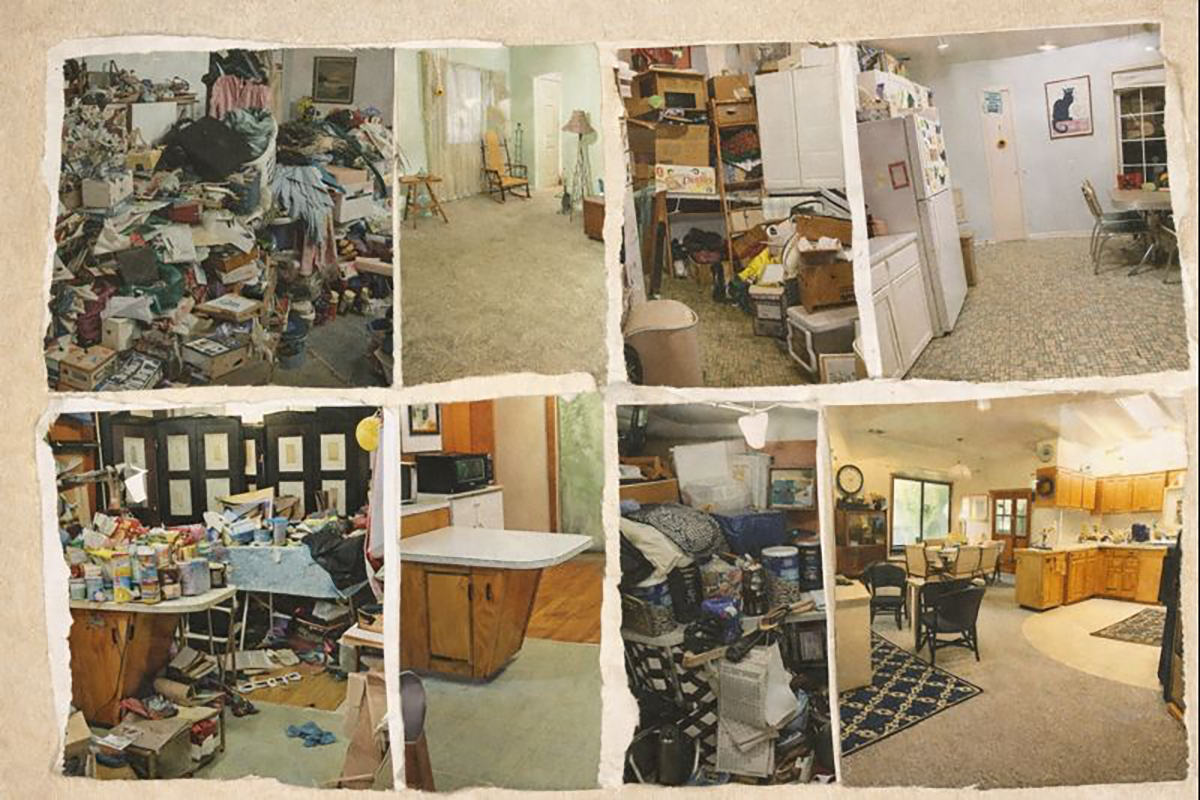

Hoarders spanned seven seasons and survived cancellation on two different networks. Two months after the lowest point of the Great Recession, “austerity” was just entering mainstream political discourse when the debut of Hoarders captivated audiences with the shocking spectacle of those whose lives exemplified the opposite. There are almost a hundred episodes of domestic horrors: piles of refuse so large and rancid that they rot through floors. Animal feces putrefying next to the small spaces the hoarder carved out to sleep. One hoarder stored full cans of gasoline in his living room. Another had seventy-six cats, thirty-five of which were dead. In each episode, a massive cleaning crew descends upon the property for a few days; meanwhile, hoarding intervention professionals and the frayed remains of the hoarder’s social network attempt to convince them to part with enough industrial dumpsters of waste to salvage the house before the Hoarders team departs.

This is never an easy task. Many of the hoarders, who are largely white, working-class women, resist pathologization. But they often have clear insight into the deep-rooted traumas from which their hoarding commenced, even if they refuse to label it as such. They tell the camera about the abuse, disaster, or poverty against which their hoard has become, as one says, “a security blanket.”

“I get enjoyment out of it, and I have very little in life to enjoy,” says a beleaguered woman whose husband bounces in and out of mental health institutions. “It’s nowhere near a replacement of my father, but it provides a moment of joy in a world where that’s rare,” says a mother who met her thirty-nine-year-old partner a decade ago, when she was seventeen. “I know I’m kind of secure because if someone tries to get to me, they would have to get through a lot of stuff,” says a formerly unhoused man in a transitional living facility. It’s unsurprising that even the hoarders willing to admit a problem are distraught when dozens of strangers descend to strip away and destroy their psychological security blankets in front of a TV crew and national audience.

At the show’s outset, hoarding was classified as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder. By the end of its run, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual had graduated it to a condition all of its own. “Compulsive Hoarding is a mental disorder,” a card informs us as each episode opens, “marked by an obsessive need to acquire and keep things, even if the items are worthless, hazardous, or unsanitary.” Hoarders tells us explicitly that its subjects are mentally ill. Psychiatrists counsel apoplectic patients sobbing on recently-excavated kitchen floors, earnestly encouraging them to connect with a therapist and repair their lives. This show, we understand, is more than just tough love. It is a therapeutic intervention on the behalf of the hoarders. This framing is what makes the final seconds of each episode so confounding: a text description of the hoarder’s progress after filming had wrapped.

In many cases, as you might expect, they’ve relapsed with a vengeance. What’s puzzling is why a show styling itself as a pseudo-medical intervention bothers to tell us that it has failed, over and over again, on its own terms—that destroying the defense mechanisms of traumatized people didn’t actually end up being for their own good at all. The show goes out of its way to inform us of the misfortunes befalling half of the subjects of its first season after filming wrapped: a heart attack, divorce, loss of parental custody, the transportation of all of the waste removed from a living room into an adjacent garage. The show has already told us that we ought not be surprised about how frequently the intervention fails. “It isn’t realistic to think in a week or two days that we’re going to clean out the house and have it stay that way long term,” a clinical psychologist tells viewers of the show’s second episode.

The suffering of hoarders getting forcibly decluttered may not have had salutary effects, but Hoarders is not truly about psychological health or even about the quantity of dirty dishes and second-hand clothes that might be stuffed in a single-family home. Hoarders is, at heart, a morality play. Its subjects are punished for what the viewer recognizes is a profound, if unspoken, sin.

The Christian West’s conception of sin—an immoral transgression that tempts because of the very depravity of the human condition—is indebted to, more than any other person, Augustine of Hippo. St. Augustine is the Isaac Newton of sinfulness, a theologian so concerned with sins that he invented the autobiographical genre in order to recount his own. When telling of the “foulnesses,” “carnal corruptions,” and “hellish pleasures” of his pre-conversion youth, Augustine fixates not on sexual improprieties or pagan heresies but, in place of Newton’s apple, a number of pears that he and his friends stole during his teenage years in Carthage. If young Augustine had eaten them afterwards, he would at least have been appreciating a part of divine creation. Instead, he and his cronies threw the pears to the pigs, since they had stolen them only for the rush of committing theft. The actual pears were as immaterial to his perverse enjoyment as the legibility of decaying newspapers is to the recluse stockpiling them.

Just seventeen centuries, a number of swine, and the grace of God kept a youthful Augustine from starting down the road towards A&E reality show infamy. “If only someone could have imposed restraint on my disorder,” Augustine would reflect, decades later. “What rottenness! What a monstrous life and what an abyss of death!” Hoarding isn’t just any sin; the enjoyment of corrupt possession is the theologically paradigmatic sin.

If debauched acquisitiveness is sin par excellence, the snares of the devil are particularly dense in the modern United States. We might say that under the reign of capital in the commodity-and-debt-laden imperial core, all political-ethical thought trends towards the standpoint of the selection, acquisition, and consumption of goods and their corollary, the proper elimination of trash, the materially and psychically necessary coda for consumption to begin anew. There is only ethical consumption under capitalism, at least as far as capitalist ethics are concerned. It has never been so easy to purchase so much, and each purchase has never before risked so much moral peril.

We might abstain from Starbucks for its wokeness or Walmart for its labor abuses or refuse such abstentions as a political act all of its own. We might only shop local or American or fair trade, purchase pillows to fight the Deep State or unbeautiful vegetables to save the Earth. We might organize boycotts or campus protests or social media pressure campaigns or any other variety of consumer revolt. We might worry what each purchase reveals about our secret selves: gluttonous or stingy, apathetic or self-righteous, ignorant or bigoted or just uncouth. We are challenged to navigate an economy that might cover us in moral indebtedness for inadvisable purchases from Amazon or Disney or, failing that, in potentially-lethal quantities of rubbish.

A number of factors have come together to create the perfect American garbage storm. Enough fighter jets and aircraft carriers to secure exceptionally favorable trade deals. The bountiful sweatshops of the colonies-turned-export-oriented-economies of the world. A domestic post-industrial economy almost entirely propped up by consumer debt.

The result is quite extraordinary. To be poor in the United States is in some ways like being poor anywhere else: the unsettling proximity to exhaustion, degradation, or death. Death from a lack of heat or a lack of food or a surplus of whichever chemical sufficed to numb the pain of the former. Death from the violence inflicted on those seen as a drag on society’s collective wealth. Death from the weight of a lifetime of arduous labor carried out by a body forced to wreck itself slowly so as to not be starved to death first. And so on.

To be poor in the United States is exceptional in that, thanks to the efforts of the good people of Dhaka and Juarez and Shenzhen, you can die in any of these ways at the very same time as you accumulate an immense volume of stuff. The hoarders on the A&E show are not people of means, yet they have still managed to acquire enough consumer goods to actually imperil their lives. “I’m going,” says the husband of a 72-year-old self-described “collector,” “to die here.”

So much American junk must be disposed of that entire moral cosmologies and major industries are based on the manner in which one chooses to do so. Discard or recycle. Resell or donate. Most second-hand clothing given to the Salvation Army and Goodwill is never purchased in-store. It’s sold to commercial dealers by the ton and begins its journey south, to be sorted in El Paso warehouses before being smuggled across the border as ropa de paca: clothing by the bale. A bale of jeans, a bale of polo shirts, a bale of skirts, divided and sold at street markets throughout the country. Half of the clothing sold in Mexico is pirated or contraband, most of it illegally imported from the U.S. On one occasion, officials seized fifty tons of it at once.

Some will continue down through Central and South America, all the way to Argentina, where second-hand goods are sold in “American Fairs.” The unloved garments that end up in Haiti are called “Kennedy clothing,” after the administration that oversaw the first large clothing donations to the island. In Mozambique, they become “calamity clothing,” named for the first world charity that follows disasters. In Ghana, they will be called “dead white men’s clothes.” There is half a world swathed in America’s cast-off refuse.

It is neither the number of humans nor even the ravenous American appetite that threatens human survival, but rather the amount of garbage, from plastic bottles to greenhouse emissions, that this consumption generates. Unusable, non-decomposing consumer waste, or what we call trash, didn’t even exist before the twentieth-century development of plastics. Such is the condition of life in what could be dubbed the Purgamentascene, the Epoch of Trash, the dozen decades that saw waste created on such a scale that it might kill off the species that creates it. Walter Benjamin called Paris the capital of the nineteenth century. The Purgamentascene’s capital rotates between several Amazon distribution hubs and the Mall of America.

Against outdated stereotypes, attempts at wild material excess are today coded as the territory of the poor. Marie Kondo minimalism is a mark of culture and taste. Even the nouveau riche have shed their taste for ostentatious display. Mark Zuckerberg claims that he only ever wears gray t-shirts so he’s not forced to waste time choosing what to put on each morning. But Zuck doesn’t wear just any gray t-shirt. He wears, exclusively, the gray t-shirt: the optimal shirt, a shirt so ideal that its duplicates fill his closet. The perfect gray t-shirt is made by Brunello Cucinelli and costs over $300. The wardrobes of the ignorant masses overflow with non-optimized attire. The lives of the elite are immaculately curated. Their housekeepers may lack the time to tidy their own homes so well.

The risk of consuming incorrectly, immorally, or in incorrect quantities swallows political thought until nothing seems more urgent than doing whatever is necessary to put the societal household in order. The hoarded home is nothing other than moral disorder freed of all restraint.

The word economy comes from oikonomia, the Ancient Greek term for household management. The very danger of succumbing to a hoarder’s household might be thought to indicate a national household very much in disarray. Such disarray is exemplified by the mere possibility of existence of the hoarder, to say nothing of her refusal to repent. Hoarders presents exemplars of the licentiousness and disorder which the private home and traditional gender roles have usually been tasked with keeping away.

“I don’t know if living in a clean and organized house would have saved our relationship, but it does play a huge part in it,” says the single mother of three whose marriage fell apart amidst the malodorous vapors of her fetid home. Her youngest daughter, only seven, writes of wishing her own death because of the conditions in which she must subsist, a fact of which both mother and viewer are well aware.

We are enticed towards sympathy for the subjects of Hoarders, only to find fulfillment in their frequent chastisement. We witness the catastrophes that their disorders have wrecked upon their spouses, children, and pets and receive gratification in their psycho-medical castigation. Were it not for our own discretion, their sins might become our own, and the consumer waste destined to become the ropa de paca and Kennedy clothing of the global periphery might entomb us as well in living death. Though superficially presenting the unrepentant hoarder as ill, Hoarders displays not the healing of the sick but the abortive expiation of the sinner.

The only palliative for the mortal death wrought by sinfulness, in the Christian imaginary, is blood–the redeeming force of the crucified God-man, he who Augustine wrote became “both Priest and Sacrifice, and Priest because he was the Sacrifice” in the course of an agonizing death upon the cross. It is only by believing in, meditating upon, imbibing of another’s blood that salvation may be attained.

Some time between Hoarders’s thirteenth and fourteenth seasons, Payton Gendron scrolled 4chan until he became convinced the only way to preserve the white race was to livestream himself murdering Black grocery store employees and shoppers. After the May 2022 attack, journalists found his one hundred and eighty-page screed justifying the slaughter. As some wrote explainers about the contents of the “manifesto,” others published articles proclaiming their own intellectual bravery in refusing to name it as such. To call this document a “manifesto,” wrote Jeffrey Barg, would “risk glorifying the writing.” Such reasoning, also followed by NPR and the Associated Press, isn’t an argument for it not being a manifesto. It suggests that Gendron’s text is not only a manifesto but a manifesto of such power that it can only be contained by refusing to categorize it correctly.

The actual reason to not call Payton Gendron’s document a manifesto is that it’s mostly product reviews. Recommendations for rifle handguards, slings, ammunition, shotguns. The rifle he used, and the rifles that would have been preferable had they been available to him. Descriptions of the specific multitool, belt, iPhone, and Bluetooth speaker he planned to take with him on his murder spree. A list of alternatives for each, with prices. Dozens of AR-15 manufacturers, ranked from worst to best. Sixty-two pages of reviews of body armor and helmets alone. Gendron left proof of an arsenal as optimized as Zuckerberg’s closet.

The majority of the text is Consumer Reports for mass shootings, the Good Housekeeping of ethnic cleansing. Most of the remainder of the document is racist memes, charts, a screenshot of his Myers-Briggs personality test results, and an absurdly precise timetable for the attack. The space left over, less than a quarter of the total length, is, indeed, a manifesto, though one which borrows liberally from that of the Christchurch shooter.

Gendron imagined himself and the random supermarket shoppers he murdered as opposing sides of the subterranean, global race war. His chief concerns were that he be recognized as a belligerent on one of its sides and that his actions be replicable by his pasty-faced comrades to follow. It was to that end that he shared his research on each and every individual product that might prove useful in a mass shooting. When forced to use a sub-optimal item, he makes sure his reader knows that this was due to circumstance, not ignorance.

A mere four pages of the document are devoted to sharing his actual plan of attack. Though he does acknowledge at one point that even with the perfect weapon, you’re “gonna suck if you don’t get training,” he immediately reveals that his own “training” was limited to dry-firing guns in his room and occasionally shooting trees. We learn nothing more about the training regimen suggested for the aspiring Aryan warrior because, in Gendron’s world, success at mass murder depends chiefly on having the right gear.

Such discriminating taste from a white consumer in fact, in Gendron’s philosophy, prefigures the ethno-state to come. The brief legitimately manifesto-y section of his text rails against “ever increasing industrialization, urbanization, industrial output, and population increase.” The original Nazis passed Germany’s first conservation laws and implored housewives to choose locally grown, organic foods to advance the food sovereignty of the nation and the vitality of its members. Gendron follows in their crunchy, jackbooted footsteps.

“Goods produced without care for the natural world, dignity of workers, lasting culture or white civilizations’ future should never be allowed into the new morally focused and ethically focused European market,” he declared. There are no hoarders in white dweeb Valhalla, only the Amazon Top Reviewers of the master race. The citizens of the ascendant Fourth Reich would doubtless have the power to take any quantity of material from the waning darker nations that they might desire, but the Ubermenschen of tomorrow would never desire unregulated accumulation.

Such desires would be banished because, in the Caucasian ethno-state, the patriarchal father has returned to put his national household in order. The “power and danger” of Nazism, wrote historian Moishe Postone, “results from its comprehensive worldview, which explains and gives form to certain modes of anticapitalist discontent in a manner that leaves capitalism intact, by attacking the personifications of that social form.”

The hoarder is said to represent the abuse of capitalist liberties. Gendron’s solution, shared in diluted form by ethical consumerists of all stripes, is not to reduce such liberties or the exploitation that undergirds them, but to reshape the consumer such that she is never tempted in her freedom by such profligacy. Were we angels, they cry, the kingdom of heaven might be wrought for us out of neocolonial extraction and war. Not sweatshop fires or lithium mines but our personal failures of discernment and prudence delay the onset of the millennium; to hasten paradise would surely justify any price.

The soul of empire vacillates between horrors. Beneath it all, the hoard; beyond it, the horde.

This article was developed by the author in conversation with Sharoon Negrete González.