An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

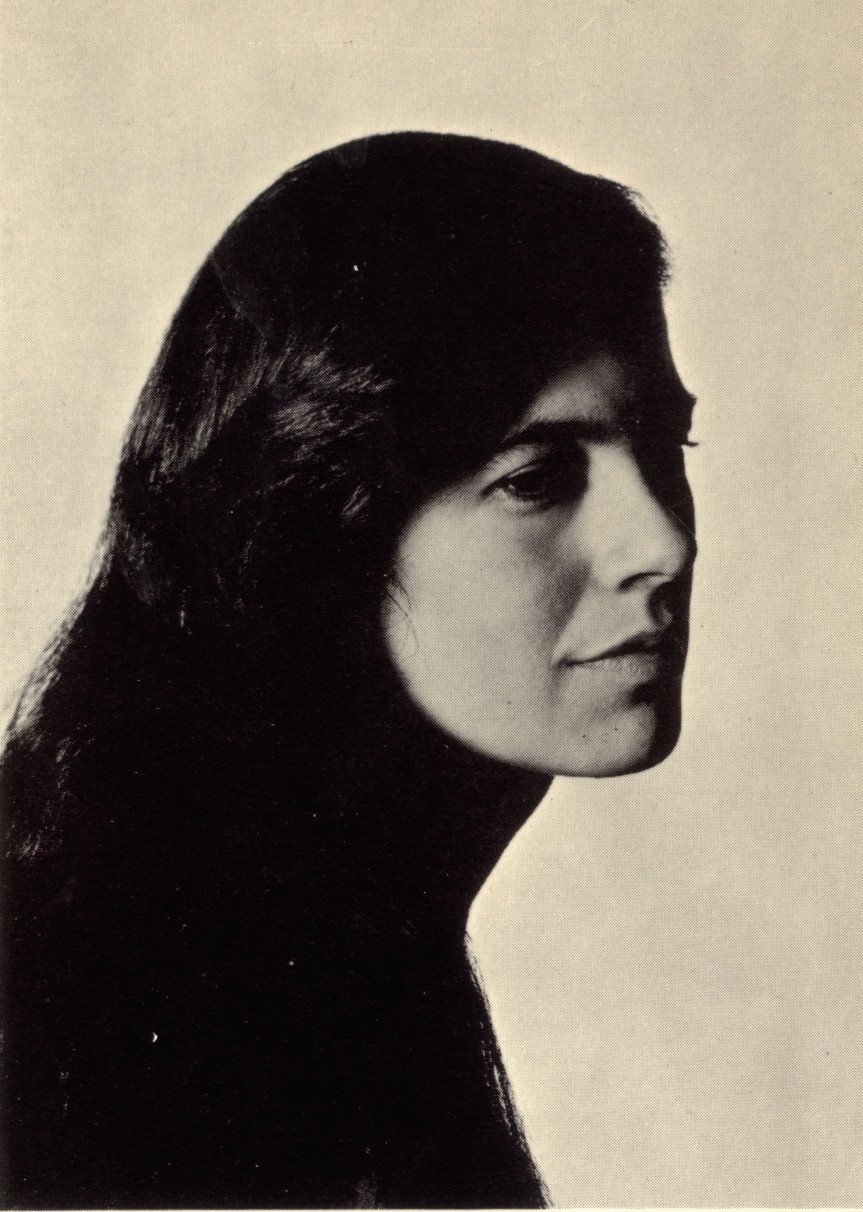

By all accounts, Susan Sontag found being alone intolerable. In Sigrid Nunez’s 2011 memoir, Sempre Susan, Sontag didn’t even want to drink her morning coffee or read the newspaper without someone else around. When she was alone and unoccupied by books, she tells Nunez, her “mind went blank” like “static on the screen when a channel stops broadcasting.” Without others to respond to her ideas, or a book to provoke them, the ideas vanished. Sontag herself substantiates Nunez's impression in the second volume of her journals, As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh. The tension visible here between the demands (and solace) of relationships and the appeal (and terror) of solitude may be a basic human circumstance. But women, in modern history, feel the tension with special acuteness, we who are assumed to be talented at interaction and rudderless when alone. It is striking that even Sontag, the most authoritative and singular of public figures — the most masculine of women intellectuals — also found the conflict vexing. The first volume of the journals charted her heady, headlong ascent into sexual and intellectual self-knowledge. This second volume, even as it spans the period of her most important work, shows her running up against her own limits. For Sontag, one of the most troubling of these was her difficulty being alone.

Solitude is a problem for writers generally, who spend so much time alone rehearsing a form of ideal communication. And men —as a practical matter — are often worse at being alone than women. But for male writers, however often an appearance of self-sufficiency can be stripped away to reveal a hidden structure of support, there is a writerly tradition of solitude that has existed at least since Romanticism: Rousseau’s “my habits are those of solitude and not of men,” or Shelley’s “Alastor; or, the Spirit of Solitude.” A man who chooses to be alone assumes the glamour of his forebears. A woman’s aloneness makes us suspicious: Even today it carries connotations of reluctance and abandonment, on the one hand, and selfishness and disobedience, on the other. Kate Bolick, writer of a much-discussed piece in The Atlantic about the “rise of single women,” became something of a spectacle for suggesting that she was happy, at 39, being unmarried and on her own. Albeit strangely titillated, many readers rallied to believe her. The rest called her deluded.

Sontag disliked how much she relied on others, and deplored her neediness and attempts to please. In the journals, she repeatedly accuses herself of “feeding” on people for their talents or knowledge. She would be more herself if she could only “consume less of what others produce.” Even the conversation she loves and lives for is suspect. She wastes herself in talk; she should talk less about her ideas because this means she is less likely to write about them. It makes sense that Sontag experiences being alone as an intellectual loss when she associates aloneness so closely with genius. In an entry from 1966, when she is 33, she dismisses herself as not having a “first rate” mind, and blames her inadequacy in part on being too dependent: “My character, my sensibility, is ultimately too conventional . . . I’m not mad enough, not obsessed enough.” What advances she has made she attributes to not having to “package + dilute” her responses for another person, as she had to do with her ex-husband Philip Rieff or her former lover Irene Fornes.

1966 was also the year she published Against Interpretation, but the success is hardly mentioned, except for a totaling up of copies sold. “Do I resent not being a genius?” she wonders, posing the question as if it’s settled she isn’t one. “Am I sad about it?” What holds her back, she believes, is not so much some missing intellectual capacity as a problem of temperament. For the “price” of genius is solitude, in fact the same solitary and “inhuman life” that she happens to be leading, “hoping it to be temporary”: “Even now — I know my mind has gone a step forward by virtue of being alone the last 2 ½ years . . .” Being alone lets you develop, become strange, be mad. If to be with people is to be socialized, to submit your rough edges to the whetstone of others’ desires, to be asocial is to be ragged and, thus, original. Wistfully, or maybe as yet aspirationally, she lists a handful of preeminently brilliant and asocial men: Wilde, Benjamin, Adorno, Cioran. But did she forget Adorno’s long dedication of Minima Moraliato his friend Horkheimer, without whom he said the book could never have been written? And all four of these men were married, even Wilde, though in his case the marriage was almost certainly less solacing than his affairs with men.

Being a genius may require being especially alone. But at least one reason to be famous (if not necessarily a genius) is to be alone no longer. Sontag points this out one morning in Prague, at breakfast by herself — so we have record of at least one breakfast eaten solo — and yet the main point of the entry is her surprised discovery of the pleasure she’s taking in solitude. It’s July of 1966, and she is at a hotel. She drinks her coffee, eats “two boiled eggs, Prague ham, [a] roll with honey,” and finds herself content for the first time in months. She doesn’t feel distracted or inhibited, and she doesn’t feel childish; instead she feels “tranquil, whole, ADULT.” Her novel may be stalled, her heart recently broken, but for a minute or two, sitting by herself at a table covered by a spotless tablecloth, her son asleep upstairs, she is at ease. She sounds hopeful, even pleased with herself. “I must learn to be alone—” she vows. Yet the resolution is less than persuasive, provoked, as it seems, by necessity. Eleven years later, when her relationship to a woman named Nicole has foundered, she is still telling herself the same thing: “Remember: this could be my one chance, and the last, to be a first-rate writer. One can never be alone enough to write.” One function of the declaration is clear: to convince herself there can at least be a purpose to her unhappiness in love.

That she would never feel finished with her work; never satisfied; never recognized in the way she wanted, as first a novelist and second a critic; that she died believing she would recover, as her son David Rieff (the editor of the journals) has noted — all of this makes these resolutions especially poignant. Then again, most people need resolutions they can’t help but break, just to get by.

***

Vivian Gornick, Sontag’s fellow critic and contemporary (Gornick was born just two years later), tried to puzzle out something that seems to have confused Sontag, and is genuinely confusing: the relationship between solitude and romantic love. In Gornick’s 1978 collection, Essays on Feminism, she argues that, at least for women, solitude is necessary because marriage, its apparent opposite, usually gets in the way of thinking, growth, self-knowledge. In fact marriage, per Gornick, is the original, distorting expectation imposed on a woman’s life — distorting because it has been viewed, by both men and women, as the “pivotal experience of [a woman’s] psychic development,” her crowning achievement. Gornick outlines the consequences of the idea in one long, electrifying sentence: “It is this conviction, primarily, that reduces and ultimately destroys in women that flow of psychic energy that is fed in men from birth by the anxious knowledge given them that one is alone in this world; that one is never taken care of; that life is a naked battle between fear and desire, and that fear is kept in abeyance only through the recurrent surge of desire; that desire is whetted only if it is reinforced by the capacity to experience oneself; that the capacity to experience oneself is everything.” The promise of marriage is the promise of togetherness, support, safety, and this prevents a woman from taking responsibility for her own life — and therefore ultimately from “experiencing” herself — by removing the motivation behind all important action, which is the terror of aloneness. In Sontag’s envy of those writers who knew how to be alone runs a current of precisely this motivating terror. Her fear of being too much by herself fuels her desire to join the club.

For all of her skepticism of marriage, Gornick, who married and divorced twice, didn’t exactly give up on love. In “On the Progress of Feminism” she describes a friend — not a feminist, she is quick to point out — who wearily pronounces love dead. Maybe it is love, this friend says, that is keeping us from self-realization. The proposition appalls Gornick. “No,” she protests “hotly” —we need to learn to love anew. If we can stop being “in love with the ritual of love,” its tired conventions and seductive abstractions, maybe we can achieve a “free, full-hearted, eminently proportionate way of loving.” Women aren’t the only ones who suffer in marriage, but because marriage is so “damnably central” to us, we are always the more comprehensively wounded party. And because we have more to lose, “it is incumbent on us to understand that we participate in these marriages because we have no strong sense of self with which to demand and give substantial love, it is incumbent on us to make marriages that will not curtail the free, full functioning of that self.”

Is romantic love the enemy of a necessary aloneness? Or is it only through learning to be truly alone that we become capable of romantic love? Put differently, is independence a necessary precondition for any relationship or, instead, an end in itself? In Gornick we feel this dilemma being lived but not quite framed. It would be heartening to find, in her oeuvre, a woman who’d been able to do something like what she envisioned, a woman unscathed by her romantic past, in full possession of the answers to her questions, a mature and sober literary hero. We can find a likeness of this image in her work, but so can we find something more provisional and trapped, a person battling the same impulses and limitations her whole life, winning some, losing some, never arriving definitively. In Fierce Attachments (a memoir of her relationship with her mother that is as much a memoir of her relationship to romantic love), she describes being questioned by a friend about her stoicism in the face of long singledom — “You seem never to think about it,” he says to her, meaning men, or rather being without one — and as he speaks she has a vision: “I saw myself lying on a bed in late afternoon, a man’s face buried in my neck, his hand moving slowly up my thigh over my hip . . .” Poor Vivian, transfixed by her internal picture, is so “stunned by loss” she can’t even speak.

So much has she believed in the necessity of being alone that she refuses, until very late, to see the toll solitude has taken. The trouble, as she dryly remarks in Approaching Eye Level, is that she is a “born ideologue.” Repeatedly trumpeted, her convictions about the necessity of independence ultimately leave behind their foundational truth. In a way, she has also mistaken her own early argument, imagining solitude itself as the goal, the necessary regulating ambition, when it was rather solitude as precondition — “the anxious knowledge . . . that one is alone in the world” — that she’d initially lit upon as useful. In that earlier formulation, aloneness was neither survival technique nor highest spiritual aim, it was the fact one started with, and this awareness would lead not to literal seclusion but to the communicative achievements of art and love. So long has Gornick insisted upon living alone, believing that she must “face down loneliness,” that she has failed to see that she was in fact facing nothing down: “I saw that I had not learned to live alone at all. What I had learned to do was strategize; to lie down until the pain passed, to evade, to get by. I wasn't drowning, but I wasn't swimming either. I was floating on my back, far from shore, waiting to be saved.”

***

A continent away, the Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik, born in Buenos Aires in 1936, wrote on a January day in 1963 in her own diary that she had been “forced” into poetry because it let her be alone. Pizarnik’s extraordinary journals, as yet untranslated into English, document a period of 17 years, from 1954, when she was 18, to 1971, the year before she killed herself. The very day before her death, she told a friend that she wanted to see the diaries published as those “of a writer.” This is very much what they are, and Pizarnik had received remarkable international acclaim for a young poet. Yet if the diaries are absorbing as an exegesis of her spare poetics, it’s as a record of her emotional life, including depression and continual suicidal ideation, that they most enthrall. The sentences are severe, arrhythmic, even choppy. Sometimes the writing becomes florid, and the flood of imagery over-dramatic, but more often it displays the kind of dry, desperate, self-aware humor perfected by the very unhappy. Like Sontag, Pizarnik too quarrels with her own ambition, one minute arguing the futility of the business — why write one more thing she’ll just have to type up, another poem destined for a stack of papers on a cluttered table? — and then, the next minute, coolly announcing that she has written the best poem in the Spanish language.

Her claim about needing poetry for solitude is at once sarcastic and sincere: “As if to deserve aloneness one has to say: I am alone in order to write. Ergo: if I don’t make poems the solitude isn’t mine anymore.” (Can we imagine a male writer worrying so much about whether he deserves aloneness?) This suggests that writing is something of an excuse for solitude. But such an impression is belied by the seriousness with which Pizarnik approaches her own work: what is most important to her, what is important above all, is the writing. And yet still she is congenitally lonely, helplessly in search of some perfect counterpart never found. There are lovers, men and women both (though they appear in the diaries only glancingly), but never the lover. Hers is an actual aloneness, simple and awful, a far cry from Sontag’s daydreams. So ruthlessly enforced, Pizarnik’s solitude seems to have helped her writing up to a point, and past that point made it impossible.

Where is that point? Sontag desperately avoided solitude while elevating it. Gornick sought it out, found it punishing, and undid it as well as she could. Of the three, Pizarnik was the truly isolated. By staking her life on literature to the exclusion of nearly everything else, she did what Sontag and Gornick fantasized about, attempted, and quite sensibly turned away from, and she did it at great personal cost. But then a total submission to literature must by definition be costly. One tormented entry reads like this:

I neither write nor read. I have nobody to talk to. Marta and Antonio show no signs of life. And why make my house beautiful if nobody who interests me comes to see me? Not even Olga is sensitive to this mortal loneliness insofar as she doesn’t call (nor Aurora nor Juanjo nor others who used to quite often). What has happened? Is it me or them? I wonder if I’m not assuming, dangerously, my mother’s loneliness. Should I do something or should I wait (and not even hope)? It is clear that I need people, at least a few.