Raymond Roussel (1877-1933) was an avant-garde French poet, playwright, and novelist. Born into a wealthy family, he devoted his life and fortune to crafting and publishing eccentric works of art that he thought would bring him universal acclaim. Alas, they only managed to baffle a few members of the French public and to be ignored by the rest. After his death, by suicide in Palermo, he published How I Wrote Certain of My Books, the skeleton key for his novels Locus Solus and Impressions of Africa and some of his other writings. There he explains that he generated his texts with an elaborate method known as the “procédé,” based on the use of puns. Though his writing was embraced by the surrealists, Roussel’s work was virtually unknown during his lifetime. He remains an obscure figure to this day, but his influence on the 20th century French and American avant-garde is unparalleled. Besides the surrealists, his admirers include Salvador Dali and Marcel Duchamp, Michel Foucault and Alain Robbe-Grillet, Raymond Queneau and Georges Perec, John Ashbery and Kenneth Koch.

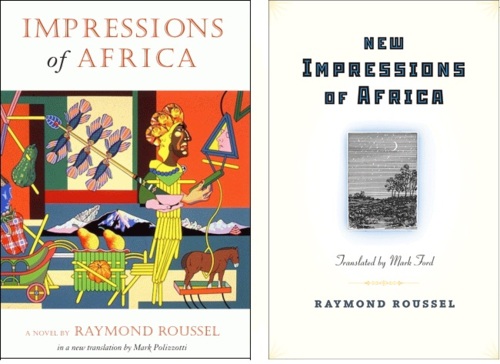

This year, two of his books have appeared in English. The first, Impressions of Africa, has been translated by Mark Polizzotti, author of books on André Breton, the Comte de Lautréamont, and Bob Dylan. Polizzotti is currently the Editor in Chief of the publishing wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The second, New Impressions of Africa, has been translated by Mark Ford, author of three collections of poetry and of Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams, a biography. Ford currently teaches in the Department of English Language and Literature at University College London.

In the following double interview, Polizzotti and Ford discuss the life and work of one of France’s strangest writers with TNI.

TNI: How did you discover Raymond Roussel’s work? What is it that interests you most about it?

MF: I had just embarked on a PhD at Oxford on the poetry of John Ashbery and in my first term of this I came across his three essays on Roussel published in the 1960s. I had to write a 5,000-word essay for what was called the MLitt qualifying exam, as I recall, and I decided to write on Ashbery and Roussel. This was in 1985 when Ashbery wasn’t that well known in Britain, and Roussel not at all. I found the modern European languages library [at Oxford], the Taylorian, had the complete Pauvert edition of Roussel and I set about reading my way through these hefty, scarlet-bound tomes. As a young person—I was 22—you are always on the look out for the obscure and overlooked or neglected, writers other people haven’t heard of, and there was a great deal of romance for me in all of this.

MP: I discovered Roussel tangentially, through the currents that took inspiration from him (surrealism, Oulipo), and through references made to him by people whose work I admired (John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, Trevor Winkfield, Ron Padgett). It’s probably the idea of Roussel that initially appealed to me more than the work itself: I’d read How I Wrote Certain of My Books, with its soberly off-the-wall exposition of his creative method, and I was familiar with Leonardo Sciascia’s account of his mysterious death. But to be honest, I don’t consider myself a “Rousselian.” I hadn’t read his work at any great length when I took on the translation of Impressions of Africa—parts of that novel, a chapter or two ofLocus Solus, some of the poetry, one or two plays. I considered his oeuvre more interesting in theory than in practice. But as I worked my way through the translation of Impressions, I gained a deep appreciation and respect for the delicate balance Roussel maintains between strict formal procedure and remarkable flights of fancy, all contained within a precise and economical use of linguistic means.

TNI: Has Roussel been an influence on your own work, preoccupations, and concerns?

MP: Since most of my writing is nonfiction, I don’t have much occasion to explore Roussel’s procédé. Where I do feel we cross paths is in the concern with concise expression. Roussel once remarked that he worked and reworked his prose to make it as tight as possible—a goal that I recognize in many of the writers I admire and that I strive to achieve in my own work.

MF: If I were to graph my periods of greatest productivity they would all follow intense engagement with Roussel. I’ve only published three collections of poems, though fairly well advanced on my cammin through the selva oscura, by which I mean I’m approaching 50. Landlocked, my first book, was written in my 20s, and the poems were all composed in a romantic rather than Rousselian way—that is, I would get inspired and write them very quickly, nearly always in 20 minutes or so, the opposite of his laborious prospecting. After that came out I was utterly stalled and didn’t start writing again with any consistency until I embarked on my Roussel biography. I had to go to Paris in the summer of 1996 to read through the Roussel archive at the Bibliothèque nationale. Over the next five years, in the wake of, or parallel to, all this reading of Roussel and the writing of my biography, I composed all the other poems that went into Soft Sift. I guess the procédéshowed me what part will might play in writing.

TNI: Despite his enormous influence, Roussel remains relatively unknown. Why do you think that is? Does the fact that three of his books have been re-released in English translations this past year signal a revival of interest in his work in England and America?

MP: I’m not sure how enormous Roussel’s influence is outside of certain rarefied circles, whether in France or the U.S. Many of the writers who have made the greatest claim to that influence are read primarily by a fairly literate, somewhat-restricted audience. Roussel enjoys more of a reputation today than he did 100 years ago, thanks to the writers who have championed his work, the critical studies that have been published about him, and the attention that has been paid him in university literature programs. But I’m not entirely convinced that he’s widely read, even so. The fact that Impressions and New Impressions were retranslated this year might be mere coincidence—though one can always hope that they will lead to more new translations.

MF: I’m not sure there’s anyone else out there willing to devote her or himself to Englishing the remoter realms of his work. I can’t see him ever becoming a mainstream writer, or becoming as popular as Jules Verne, as he thought would happen. In the grip of la gloire while writing [his poem] La Doublure he also claimed he felt he was the equal of Dante and Shakespeare, and, fervent Rousselian though I am, I wouldn’t want to suggest that that’s an assessment that will ever receive wide support.

TNI: What were some of the challenges of translating Roussel?

MP: The thing about Roussel is that, although some of his writings (Impressions of Africa being a prime example) were generated by the procédé—resorting to puns or double entendres to generate portions of text—his use of it was kept behind the scenes, a kind of scaffolding that disappears once the textual edifice is built. Which means that, while it’s interesting for a scholar to know how certain characters or incidents were derived, ultimately the French reader would have been no more aware of this genesis than an English reader would. In many respects, translating Roussel poses very similar challenges to translating any author: the delicate balance of preserving voice and tone while making the text read fluently in the target language; the quest to deliver to your reader an experience analogous to the one Roussel’s French readers would have, taking into account differences in time, culture, language, and so on. And on top of this, as mentioned earlier, the particular economy of language and deadpan humor that are peculiar to Roussel’s narrative prose, which I put great effort into trying to recreate in an English idiom that a 21st century Anglophone reader would recognize.

MF: Well, New Impressions does not make use of the pun or procédé—its method, so to speak, is not disguised as it is in Roussel’s fiction and plays, but is immediately apparent in the brackets and footnotes. The “puzzle” the poem solves is not buried but foregrounded, though the concept of the poem can be seen as developing out of his experiments with the procédé. Anyway, it presents various problems to the translator; it’s all written in rhyming alexandrines, alternating masculine and feminine rhymes. In my version I just wanted to make the meaning of the French as clear as possible. There is nothing at all surreal or inexplicable in the poem; it’s more like a crossword puzzle, and you have to work out the answer to the clues. My notion was to present a version that would allow the reader with even fairly minimal French to make sense of the original.

TNI: In How I Wrote, Roussel wrote that the use of the procédé does not necessarily lead to the production of good writing. But he doesn’t provide any further criterion, as a critic might, for what constitutes good writing. Does the value of Roussel’s work survive in the absence of his compositional methods and formal innovations?

MP: Roussel is interesting from a craft perspective because of the procédé. It’s also interesting to trace his influence on various currents that succeeded him. But if he’s still worth reading today, it’s because he used his method to produce a truly enchanting and engaging narrative. The thing we mustn’t forget in all this is thatImpressions of Africa is a good story and not just some literary curiosity. It’s an odd story, admittedly, in which an almost conventional adventure-tale backdrop provides the stage for a series of wonderfully outlandish occurrences, giving the whole book the pervasive and unsettling atmosphere of a dream. But it’s a story (or rather, a series of stories within stories within stories) that grips the reader and carries him or her through to the end. At that point, the formal innovations that helped generate the story become almost secondary, of technical rather than literary interest.

MF: Reading Roussel is not like reading anyone else. And that’s pretty important. All writers attempt to find their own voice, or whatever, become distinctive, different from all other writers, and Roussel certainly did that. While reading him one’s dominant emotion is amazement, amazement at the bizarreness of his images. His best works, Impressions of Africa and Locus Solus, are really not hard to enjoy once you accept you are not reading a conventional novel; New Impressions takes a bit more effort, but is very, very rewarding in the end.

TNI: André Breton considered Roussel and the Comte de Lautréamont to be the forerunners of surrealism. As someone who has written extensively about all three of these writers, what were the specific aspects of Roussel and Lautréamont that Breton found so compelling to the development of his own aesthetic?

MP: Breton stressed that the aesthetic experience he most valued was the one that left him with “the feeling of a feathery wind brushing across his temples.” His most cherished goal for surrealism was to recreate that sensation in everyday life, to infuse humdrum daily experience with that sense of childlike wonder. I believe his attraction to Lautréamont and Roussel derived from this. How could one not feel a similar wind when encountering Roussel’s zither-playing worm, or God’s abandoned hair in [Lautréamont’s] Maldoror? That’s how I read Breton’s appreciation of Roussel as “the greatest mesmerizer of modern times.” To a large degree, the experiments of surrealism, whether automatic writing, dream explorations, the exquisite corpse, the sleeping fits, or random explorations of the city, were so many attempts to recreate the sense of wonder that Breton and his fellows encountered when reading authors like Roussel.

TNI: As Roussel’s foremost biographer in English, what do you think drove Roussel to a literary life in the face of the overwhelmingly poor public reception he recieved?

MF: I think he had a compulsion to write. Yes, he had no interest in being part of an avant-garde, though he did of course send the text of How I Wrote to the surrealists just before he left for Palermo, where he committed suicide in 1933. He was just not one of those artists who could belong, or “fit”. I suppose that makes him like other “outsider” artists, such as Henry Darger or, say, John Clare—their wiring is somehow different from that of other writers or artists who learn how to find a niche in their contemporary culture. But maybe their particular power, a power that can be almost scary, comes from their inability or refusal to find or accept a niche, to fit in. Certainly artists stand a better chance of becoming known and successful if they can be branded and labeled as part of a given movement, but Roussel was absolutely averse to all compromise. He was lucky to be wealthy enough not to have to worry about the profitability of his books, which were all published at his own expense. But the larger secret of why he wrote the peculiar way he did has never come to light—and in my opinion never will.