This is the editorial note to TNI Vol. 35: Sick. View the full table of contents here.

Subscribe to TNI for $2 and get Sick (and free access to our archive of back issues) today.

***

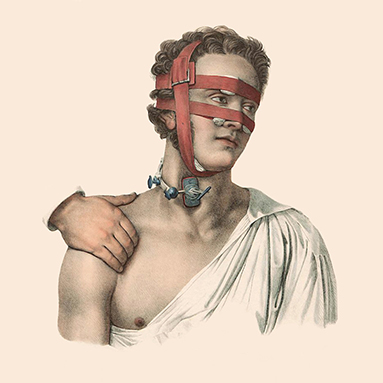

Being sick changes your relation to your body and how you inhabit it. As an experience, it is stubbornly untheoretical, even though it oozes theory, infecting concepts of cleanliness, system, and body with its disorder. Mutated understandings proliferate from sickness that lance falsely clear categories, revealing the orderliness of the world to be a form of disease. What is clear is that clinically treating biological pathogens as the sole source of corporeal trouble is an efficient way to wipe clean the structures that weigh on our lives.

Earlier this year a report found indigenous Americans suffer PTSD at the same rate as Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. This year too, Eric Garner was choked to death by a NYPD officer, but chalking his murder up to either banned maneuvers or chronic asthma is to ignore the sickness of the social order that brought Garner and his murderer Pantaleo into such predictably lethal contact. The past hundred days or so have seen the deadly toll of the social order, which steals lives as steadily as a heartbeat. That order has come under revolt by people immune to the political delusions that take such a body count to be an index of civic health.

It’s easy to say that capitalism makes us sick, white supremacy makes us sick, misogyny makes us sick, and mean it quite literally. What and where it hurts is another question, and why may be beyond our scope. But in this issue of The New Inquiry, our contributors attend to their illnesses. Hannah Black writes of the toll of losing someone to schizophrenia, of the death-in-life that you have to accept when it dawns on you that you no longer exist in a shared world. Caring for a person with a mental illness forces you beyond all measure, she writes, which is why it often falls to women, who live partly outside of measure, and often makes them crazy too.

Another kind of crazy-making death-in-life is is living with the knowledge that you have tried to kill yourself, as Natasha Lennard writes in “On Suicide.” Questions of intent are necessarily hazy in this act, which confounds the subject-object split beloved of philosophy but doesn’t make it any easier to put to rest. Trying to die, but in a state that means you can’t really mean it, means you’ll struggle with coming to terms even with your failure—as if there even are terms to come to.

Evan Calder Williams writes of the experience of diabetes as a transformation of your body into a siphon through which the world pours itself. Historically, diabetes has been understood through its liquids—insulin, urine, blood that must be constantly drawn and read. Diabetes is the condition of no longer being able to take what’s supposed to be good for you, but it forms subjects whose existence depends on the same circuits of production that made them sick from the start. Trapped between refusal and fidelity, of course they are targets of shame.

In “Weight Gains,” Willie Osterweil examines the equally shame-ridden problem of obesity, though its medical status isn’t nearly as stable as that of diabetes. Instead, he finds it to be a product of capitalist agriculture’s need to find a place to store its glut, which it resolves (as always) with the bodies of workers. If anything about obesity is a sickness, he writes, it’s that the global food market is structured precisely like an eating disorder, sending consumers spinning from diet pill to subsidized corn.

In “Taking Shit From Others,” Janani Balasubramanian writes of that most shameful substance, shit, and the miraculous cures it promises, if only the FDA would get past its squeamishness and let a thousand transplanted microbiomes bloom. The digestive system, like a body within a body, is the where the world flows through us.

Racialization is another way the world gets inside us. Yahdon Israel takes a serious look at the racial ramifications of cooties, turning the playground malady into a lens through which to examine the level of light required for passing a black body as a white one. For a black child trying to understand how the world sees him, cooties signal the racist threshold between “good” and “bad” bodies.

In “Who Cares” Laura Anne Robertson writes of the gendered infrastructure of care work, reading her job as a nurse in a mental health-care facility through feminist theories of the relation between gender and labor. Anne Boyer writes of breast cancer as a uniquely destructive force in women’s intellectual history. If women do not die for each other, she writes, they die of being women.

In our reviews section, Derek Ayeh assesses Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal, recently a presidential pick for the First Daughters. American medicine fails the dying, he writes, and makes examples of deliberately chosen death, like Brittany Maynard’s, appear as relief from industrially extended sickness. He finds Gawande’s critique of medicalized death to be compelling, and even more, his recommendations of what doctors should do instead to be practically and applicable advice.

Reviewing Eula Biss’s new book On Immunity, Sara Black McCulloch finds that the divisions immunity relies on (host, body; sick, well) has given rise to a whole host of sick programs: eugenics, miscegenation laws, and forced sterilization of genetically “undesirable” mothers. But this obsession doesn’t even have a clean starting point—we’re born impure. Instead, a real understanding of immunity would take its true lesson to heart, that both the threat and the treatment must come from inside the body we all share.

Sickness, as treated in these pages, becomes a name for the ways the world makes individual bodies bear its weight. Illness is either rebellion or submission, our bodies rejecting a foreign pathogen or succumbing to a weakness in our defenses. Examination can’t always diagnose, but perhaps it can prompt healing.