This is the editorial note to TNI Vol. 54: Bugs. View the full table of contents here.

Subscribe to TNI for $3 and get Bugs (and free access to our archive of back issues) today.

• • •

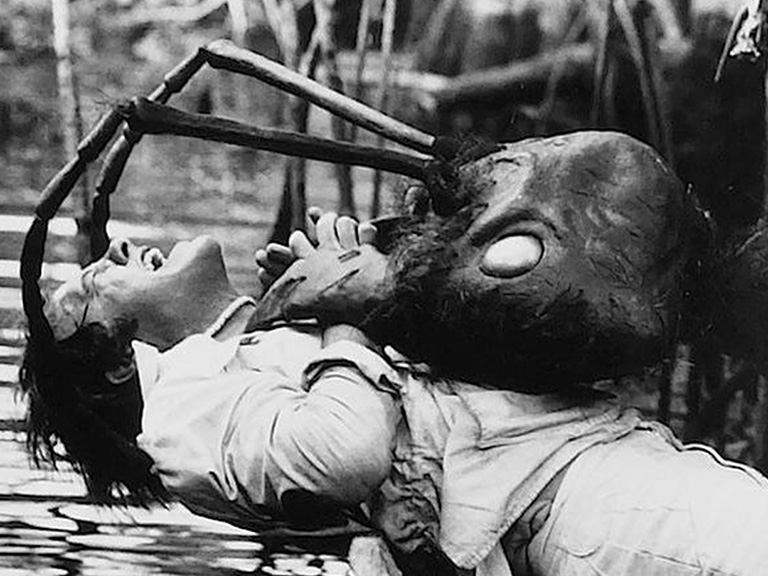

AS we write this, an ant is crawling on our forearm. More than any other non-human lifeform, bugs of any size -- the term can refer to a virus, bacterium, or arthropod -- challenge the serenity of life under human command, which in the anthropocene means nearly all life. We have taken the ant between our fingers and crushed it. While the suppression of our animal-being defines us as a species, proximity to larger beasts isn’t as much of a threat to humanness as contact with bugs. In fact, living intimately with wild or domestic creatures of the proper size can make you an exemplary human -- a hunter, herder, or farmer. Except for silkworms and bees (we’ll get to that), bugs mean you’ve lost your self-control.

If there is one ant around, there must be more. The thing about self-control or mastery is that it’s a fantasy: the bugs are always there. They’ve always been there and they’ll always be there. They live in our skin, on our faces, in our guts. Bugs exceed us. There is no human space they can’t go. And recently, it’s become clear that the drive to exclude them from our society has left us vulnerable. Less than a century of widespread antibiotic use altered human immune systems for what seems to be the worse, while allowing the surviving bugs to attain superpowers. The CDC recently reported that one in 25 current patients suffers from one of the many infectious hospital-acquired superbugs, and new studies regularly claim farm air, with its dust and manure, inoculates children against the epidemic of asthma in sterile, immunologically destabilized suburbs. Bugs, it seems, are a feature of human society.

The image of a bug-free home is nevertheless an enduring one, writes Alicia Eler in her essay for this issue. No matter how much we want to take refuge in the myth of the home as protection from strange intruders, both insects and listening devices are most likely to be brought in by intimate partners. “The bugs in your home, whether part of wiretap or of the insect variety, represent a vulnerability,” Eler writes, and the so myth of cleanliness is more about a psychological than domestic state.

Our response to that vulnerability is a political choice. Kathryn Hamilton meditates on the problem of hospitality, prompted by discovering a copy of Derrida’s lectures on the subject in a train compartment she was occupying for the night. Derrida distinguishes between a “guest” and a “parasite,” a distinction charged with mortal weight in the Istanbul where she is currently living, where refugees have travelled the semantic spectrum from invited guest to disruptive intruder. Pressing on the Greek origins of “parasite” as dining companion, she leaves us with a wish for a world that understands guests as positively transformative -- like hairworms, a parasite found in pig stomachs that has been shown to treat chronic human disease.

Putting bugs (or guests) to work for us to justify their presence in our midst says more about our societies than theirs. In Khairani Barokka’s “Colony Control,” the division of ant labor goes under the magnifying glass as she sketches an imaginary where the hierarchical structure of anthills reveals more honest human realities. “Biological determinism might not be official dogma in management handbooks anymore, but it is the presumptive tenet in the manifestation of economic systems,” she writes.

The work of debugging itself rests on a stratification of labor: only some bodies can be trusted to clean code. Grayson Clary interviews Katie Moussouris, Chief Policy Officer of HackerOne, about the Department of Defense’s bug bounty program, where the Pentagon pays hackers to find the vulnerabilities in their systems. Unsurprisingly, the Pentagon is wary of letting people who would otherwise be criminals -- it’s a felony to even look for a vulnerability on a site under anti-computer-hacking laws -- probe their code, but Moussouris was able to convince them. Issues of valuation, child labor, and outsourcing trouble the newly legal market for bugs, but that only goes to show that the metaphorical extension of bugs into the virtual brings with it all the baggage of the real.

In “Virulence in the Virtual,” Remina Greenfield writes about the “first extensively printed account of virtual rape,” which took place in 1993 through a text-based online community called LambdaMOO. The virtual worlds in which we escape the bug-filled “real one” can’t be so simply made separate. “Certain virulent patterns are deeply ingrained in virtual communities,” Greenfield writes, and it’s a mistake to claim the boundaries between virtual and real are firm to begin with. To do so is to partake in the fantasy of the bug-free world, which, as we have seen, leaves you vulnerable to the survivors.

The thought of a world without one specific bug, however, is attaining greater and greater reality. Lauren Duca brings us the “darkest meme” of our age: “The bees are dying globally at an alarming rate.” This meme is the truth, and it is the truth about our helplessness in the face of the truth, too, “poking at our shared sense of existential doom in hopes explicit acknowledgement will numb the pain of our inescapable inner darkness (haha),” Duca writes.

The historical link between darkness and pain is not so easily laughed off, though. In a moving account of her history of treatment, Karla Cornejo Villavicencio addresses the “bugs” of severe mental disorders, and the ways young people of color experience these disorders with the added burden of diverging from the face of these illnesses, the young white woman. The pain young people of color suffer is met with overdiagnosis, because, as she writes, “men and women in uniforms, whether white or blue, think somehow that our blood’s not red like theirs.”

Bugs are the stumbling block that reveal the fatal flaws of our fantasies of seamlessness and conformity. They carry within them the image of a world that exceeds our control and therefore they promise destruction. Taking bugs seriously means attending to what we attempt to exclude, and seeing how this constitutes what we wish to hold onto. Bugs may not not hold the answers, but they do not pretend to. Instead, they swarm on, indifferent to the meaning we want them to bear.