I think about The Zone of Interest (2023) while I am making my kids’ lunches, running their baths, folding laundry. Similar domestic routines make up much of the film’s action, the center of its study of how the institution of the family confers a mirage of humanity and morality onto its participants. Saturated in soft light, Broderie anglaise linen drying on a clothesline in the sunshine, the film shares an aesthetic with Julie Blackmon’s whimsical photographs of domestic life, and the Höss’s backyard recalls Esther Greenwood’s observation in The Bell Jar that a neighbor’s lawn is strewn with the “the whole sprawling paraphernalia of suburban childhood.” Toy cars, floaties, dolls, and bicycles.

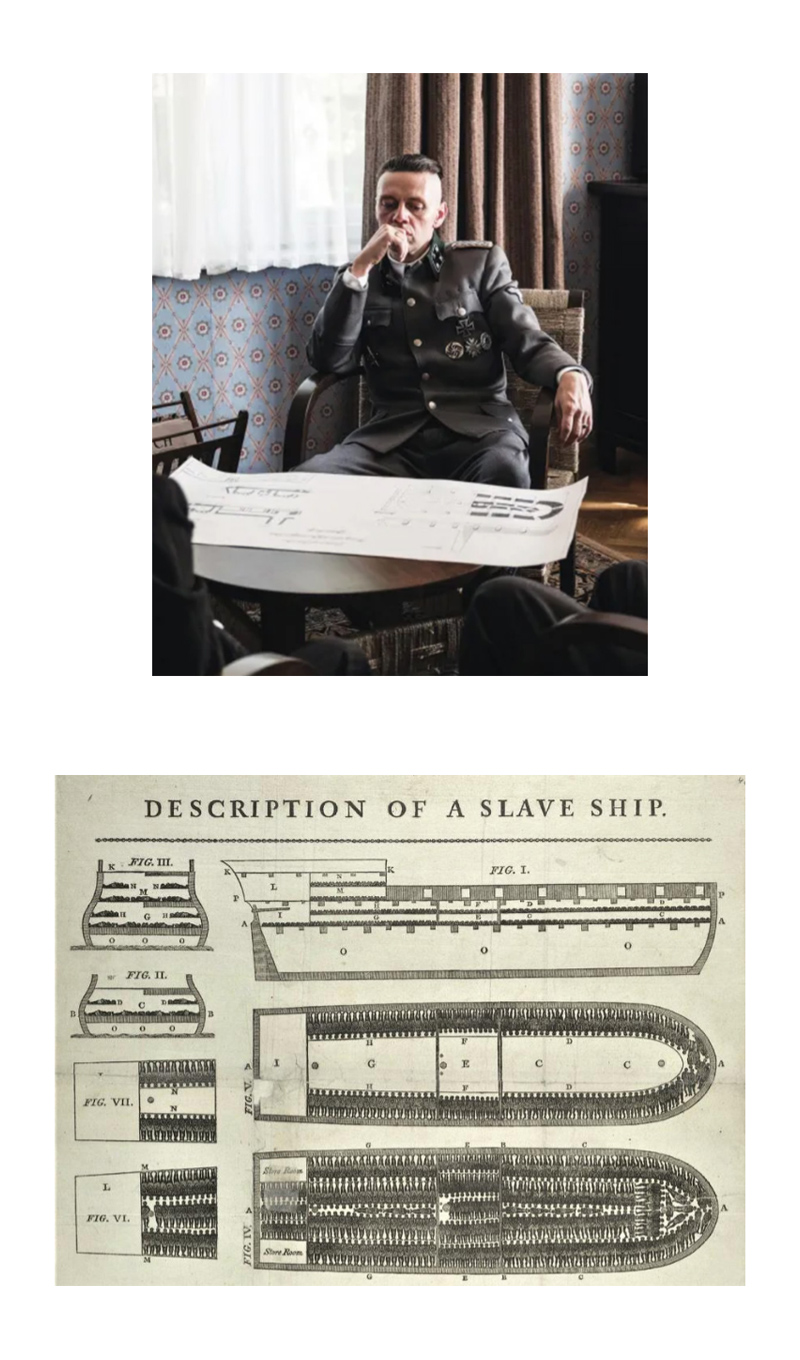

These symbols of cherished childhoods and the good life secured by family-making are what we see instead of human suffering. Other than the fleeting glimpse of a striped pajama and the incessant smoke from incinerating bodies, the film depicts none of the horrific visual tropes of the Holocaust genre. Instead, we spend a languid summer with the Höss family. The husband, Rudolf, is a commandant at Auschwitz. The film focuses on the intimate life of his wife and children—bedtime stories, day trips to a local river, a visit from a grandmother.

Glazer has spoken about his interest in making a film specifically about quotidian Nazi life. As he explained, “I wanted to dismantle the idea of them as anomalies, as almost supernatural,” Glazer told the New York Times. “I wanted to show that these were crimes committed by Mr. and Mrs. Smith at No. 26.”

Consequently, many have seen this film as an expression of what Hannah Arendt called the “banality of evil,” a concept she developed in her book-length analysis of Adolf Eichmann. The term refers to how bureaucracy normalizes evil and how following administrative protocol circumvents a critical engagement with the consequences of one’s actions. But such a characterization does not exactly apply to Höss, who is not a mid-level functionary but rather a principal architect of Jewish extermination, nor does it account for the film’s other protagonist, Hedwig Höss, the self-described “Queen of Auschwitz.”

Indeed, the notion that the “banality of evil” is the film’s primary concern overlooks its particular focus on family life itself as the structure that animates unspeakable malevolence. The film’s real subject is bourgeois domesticity, the mundane concerns of child-rearing, household management, class striving; it is about the way the private family becomes its own fortress and how its insularity, atomization, and privatization enable horrific violence.

In this sense, The Zone of Interest can be better understood in the context of recent scholarship on family abolition, white supremacy, and household work. Sophie Lewis, Tiffany Lethabo King, and others have pushed back against the family as the most natural, desirable unit of society and suggested other ways to imagine the distribution of material and affective resources to which it is tied. As Kathi Weeks writes, “The family’s utility as a site of social reproduction is predicated on the ways it naturalises hierarchy, constricts us socially and privatises care.” The bulk of Glazer’s film dwells on the operations of the family home, drawing attention to the gendered division of labor and the ill-treated female servants who perform the menial work needed to prop up the bourgeois family and ensure the reproduction of the system as a whole.

Beyond the interior spaces, much of The Zone of Interest takes place in the family garden, which abuts the fence surrounding Auschwitz, reminding us that these structures are mutually constituted. The Höss’ elaborate vegetable and flower garden signals the Nazi obsession with selective breeding and the cultivation of superior races, but it is perhaps even more strikingly a comment on how tending one’s own garden, or running a home, is an all-consuming project focused on the growth and nurturance of private life. As Hedwig shows her visiting mother around the meticulously tended, fecund vegetable beds, she remarks: “It’s a paradise garden.” Hedwig’s mother, Linna, who once worked as a housekeeper, admiringly remarks: “To have all this . . . you have really landed on your feet.” In response, Hedwig boasts, “It’s all my design,” a comment that chimes with her husband’s pride in designing efficient gas chambers. These are not separate projects: we learn that the garden is literally fertilized with human ashes.

Midway through the film, the imbrication of domestic and political projects is cast even further into relief. When Rudolf reveals to Hedwig that he has been transferred and that they will likely have to leave their home at Auschwitz, she pleads for him to find a way to enable her to stay: “Everything the Fuhrer said about how we should live is exactly how we do. Drive east, Lebensraum. Here it is.” According to Hedwig, they are living the German dream. “Lebensraum,” which refers to the German idea of “living space,” is a colonial concept akin to manifest destiny that was adapted to serve Nazism’s genocidal vision. The notion of Lebensraum links family comfort with genocide and settler colonialism, but it also euphemizes those connections and naturalizes the state’s insidious agenda through the practice of domesticity. By cultivating occupied land and bearing children, Hedwig has dutifully fulfilled Hitler’s instructions to expand the reach and size of the Aryan population and their bucolic lifestyle is both the project and the reward.

The film indulges in decadent close-up shots of blossoming flowers, dwelling on their almost surreal vividness. Such shots invoke the eugenic obsession at the heart of the Nazi program, foregrounding the role of the family in the colonization of resources and in the production of superior types. But there are no close-ups of human faces, just human screams barely audible in the background. With such close-ups, Glazer is revealing something about what the family does to scale and focus; the outsized images of flowers suggest the disproportionate attention lavished on domestic endeavors even while human beings next door are subjected to gruesome acts of brutality. Glazer asks us to see the private family as a moral vacuum that trains attention inward, directs resources toward itself, and refuses to look beyond its own walls.

Glazer worked on the film for almost a decade; he could not have predicted the relentless air strikes and enforced starvation that Israel has wrought upon the people of Palestine since 1948 in the name of establishing a Zionist state. And yet this is a film about how the White family within the Nationalist project does not merely condone such violence; it authorizes and demands it.We can thus understand Glazer’s film as not just about the Holocaust but about how family, domesticity, and the private sphere have produced such horrors across time.

While The Zone of Interest is set in 1943 in German-occupied Poland, its focus on the juxtaposition of the family and the camp readily evokes the same structure in other historical moments of humanitarian crisis. The garden scenes in particular conjure the plantations, or labor camps, of the antebellum South, another period in which the family home was interwoven with state-sanctioned racially-specific violence and abuse. Just as the Hoss family home life operates in conjunction with the activities of Auschwitz, so too were plantations “total institutions” that encompassed all aspects of life for those that lived within them. Enslaved people toiled under duress in fields and in homes alongside white leisure and domestic ritual.

Anti-slavery literature relied heavily on sentimental representations of families inside the slave system. Scenes of family separation, mourning, and suffering served to catalyze moral outrage: how could any good Christian tolerate such things? In the final pages of her blockbuster novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe famously urged readers to “feel right” about slavery, exploiting the identificatory premise of family life as a potent tool for political transformation. The novel’s sentimental project presumes that humanity (“feeling right”) emerges through normatively inhabiting one’s assigned family role. Sentimental abolitionist literature thus made family feeling the currency and goal of its emancipatory praxis.

More recently, critiques of the family’s role in propagating oppressive structures come from queer theory. In their classic essay, “Sex in Public,” Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner describe how heteronormativity enshrines the family as a normal, universal ideal, the sign of moral goodness par excellence, rendering all other social and sexual arrangements as inferior and/or pathological. As they write, “Intimate life is the endlessly cited elsewhere of political public discourse, a promised haven that distracts citizens from the unequal conditions of their political and economic lives, consoles them for the damaged humanity of mass society, and shames them for any divergence between their lives and the intimate sphere that is alleged to be simple personhood.” In other words, the hetero-family is endowed with “a tacit sense of rightness and normalcy” even as it supports gross inequality and produces those living in other arrangements as criminal and deviant.

Heteronormativity fortifies the myth that having children makes us more human—that a “family man” or “mother-woman” (to borrow a term from Kate Chopin) is a figure who has been ushered into a particular form of empathy and tenderness. The Zone of Interest systemically deconstructs this myth. We see Rudolf curled up beside his daughter in a twin bed reading her a bedtime story; Hedwig urges her bonneted baby to inhale the scent of a dahlia. And yet, these acts do not make them more human. Rather, they co-exist with—and underwrite—multiple forms of violence, from the mass murder of those imprisoned in concentration camps to the casual subjugation of domestic servants. Indeed, we might read Glazer’s project as a queer project for it asks viewers to feel disgust at what has long passed as the “social norm and ideal.”

The Zone of Interest exposes the family as a site of exploitation in its portrayal of outsourced domestic labor as constant and grueling. Significantly, it is Hedwig’s mother, Linna, a former housekeeper, who cannot abide living in such close proximity to Auschwitz, who cannot stomach the mingling of her infant granddaughter’s cries with those of the people suffering out of sight on the other side of the wall. She departs without warning and Hedwig deposits her farewell letter in her oven, a gesture that evokes the ovens on the other side of the wall, a sign of Hedwig’s own inhumanity and her eagerness to destroy the humanity of others. In a fit of rage, Hedgwig warns a presumably Jewish domestic worker: “I could have my husband spread your ashes across the fields of Babice.” Her comment exposes the private home as a realm of frightening disempowerment for domestic laborers and reveals the circuit of cruelty between the home and the world beyond its walls.

One wonders whether it is Linna’s own history as a housekeeper that makes the situation intolerable to her or whether some individuals simply have a lower threshold for atrocity. The fact that we learn about her past as a domestic worker is certainly not insignificant in light of the film’s attentiveness to the feminized labor that enables the family to operate. A sizable staff of domestic laborers clean, cook, and otherwise care for the Hoss property and its inhabitants. Domestic laborers know what is under the fingernails of the private bourgeois family: they furiously scrub the children who have accidentally bathed in a river with Jewish remains; they hose the gore off the officers’ boots. The family is the place where horror is laundered and polished. Because she used to perform such labor, Linna has gained knowledge that makes it impossible to look the other way. Her departure is not sufficient as an act of protest, but it does contain a faint hint of potential solidarity between exploited household workers and other subjugated people, alliances beyond the family.

In the film’s denouement, Rudolf is reassigned to a location closer to Berlin, temporarily leaving his family behind in Poland. On his way out of a party celebrating his promotion, Rudolf finds himself retching in a stairwell, a visceral but unconscious reaction to the perversity of the life he continues to live. The film withholds the scenes of gruesome violence; it never subjects viewers to an encounter with what is happening inside Auschwitz. Where Stowe wanted her readers to cry, Glazer wants us to gag, to feel the queasiness of our complicity. Glazer’s commitment to the tight focus on the family denies his viewers the opportunity to gasp or grimace, to feel the comforting assurance of our own moral rectitude. We never bear witness. This visual restraint recalls Christina Sharpe’s recent claim in Ordinary Notes that “spectacle is not repair.” There is no affective shortcut here to let us off the hook; all we can feel is disgust.

In the final scene, the film abruptly cuts to the present day. Workers prepare to open the Auschwitz Museum, fastidiously cleaning the structures that incinerated hundreds of thousands of bodies. Their focused labor, spraying the glass and vacuuming the floors, echoes that of the domestic workers who labored in the Höss home. But this labor is for the public; this is the work of history and memory-keeping. These final quiet scenes acknowledge the often-concealed work necessary to preserve history. And like the film itself, these shots of the museum draw attention to the power of framing and remind us that history requires its own forms of care work.