The state's racist response to the Standing Rock encampment has alienated some from the ballot box. A dispatch from Nanjala Nyabola.

IMAGINE a stand-off between the police and a group of protesters that extended beyond two hundred days during an election year and culminated with a handful of teenagers being shot in the face with rubber bullets and bean bags--but which didn’t receive wall to wall coverage, and to which neither major presidential candidate was compelled to respond.

It’s difficult to imagine because of how activist organizing has shifted the political agenda in America in the last five years. Groups affiliated to movements like Black Lives Matter and Dream Defenders forced both major-party presidential candidates to address the lives of black people and immigrants in America, however ineffectually they may have done so. But on the eve of another historic election in the United States, the deafening political silence on Standing Rock illustrates how Native Americans have been locked out of mainstream American politics and of the harm that they endure because of it.

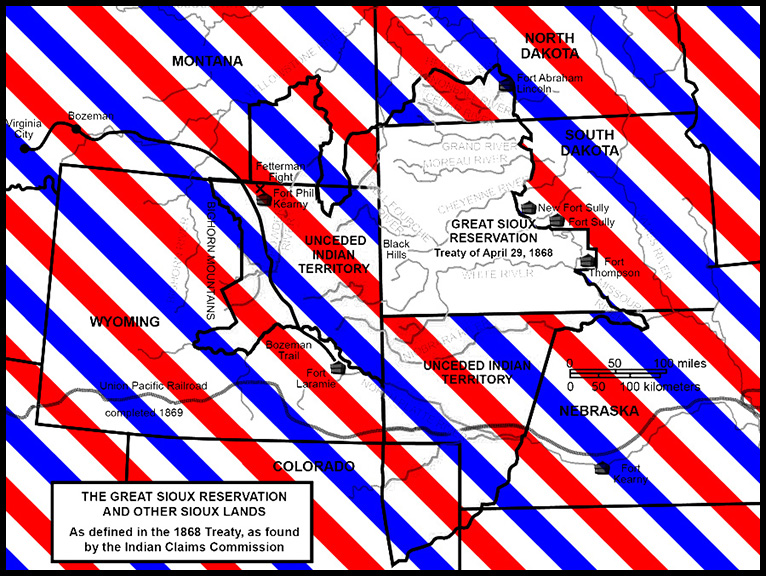

From Standing Rock, where I spent a day observing and talking to protesters, it is hard to tell a story about climate change or about America’s “energy independence.” For many protesters, this is simply the latest attempt to eradicate Native Americans on Turtle Island. This is why over 300 Native American tribes have brought their flags to Standing Rock in an unprecedented show of solidarity: they are tired of the expectation that Native Americans should silently, but spiritually, bear the constant threat of imminent extermination, while others use their suffering as a crutch for their own self-righteousness or even as a Halloween costume. The Dakota Pipeline is only the latest chapter in the American history of Native American genocide, a story of forced evictions, the persistent undermining of longstanding, legally-binding treaties, and the range of harmful land-use choices made by powerful corporations and their host states. When the pipeline was diverted from upstream of majority-white Bismarck--onto contested, un-ceded land that holds sacred Native American burial grounds--the weight that was given to concerns that it might contaminate the water in the city only underscored that in the US, some lives matter more than others.

Consider the sheer amount of energy and money that has gone into policing the Oceti Sakowin camp. Democracy Now calculated that over 10 million dollars will have been spent by November 7 on policing peaceful protesters, activists who have explicitly rejected violence and focused on prayer and spirituality. “The police came here looking for a fight,” I hear from Darrell Marcus Kills-In-Sight, a Sioux elder who points to the armored vehicles and floodlights perched on a hill overlooking the camp. While he and I are speaking, we are approached by a nervous-looking, young white man who is unabashedly eavesdropping on our conversation. A camp security guard approaches Darrell, to ask a question, and the young man interjects, offering himself as a witness to an alleged drowning on the camp. No one is aware of the incident he claims to have witnessed. He is encouraged to report it to the police, but as he leaves my three Sioux hosts look at each other nervously. “The camp has been infiltrated,” they share; “these people are looking for trouble and they’re not even doing a good job of hiding it.”

Pointing out the row of police floodlights overlooking the camp and the drones of police aircraft above, Kills-in-Sight asks “Why spend so much money policing peaceful protesters?” and then answers himself: “It’s systemic racism. They see us as a threat even when we’re just trying to survive.”

Systemic racism is not just in the police who came looking for a fight; it’s the fact that it’s taken so long for Standing Rock to register as a national issue (if indeed it has). This silence-as-violence is the space that Native Americans occupy in the US public imagination. In one version of the story, Native Americans are violent and dangerous people that were successfully subdued; wearing their traditional garments as costumes or naming sports teams by racial slurs against them are spoils for the victor. In another, they are mystical, magical people, whose spirituality can be invoked to validate others’ life choices, without ever having to engage with Native Americans as people. Both these iterations deny Native American people their complete personhood.

For the people at Standing Rock, this is more than a struggle for the environment. “I didn’t come here because this is an environmental issue,” says Rik Kapler, a white, gay ally of the cause; “I came because it’s a racial issue.” The environment-only argument ignores the politics of marginalization, violence, and exclusion that leave many Native Americans with protest as their only recourse. The companies that own the Dakota Access Pipeline see the land as vital to their project, but if it were just a question of land, then financial compensation would have taken care of those anxieties. Rather, the protest is about a community that has signaled that what lies underneath the land--sacred and burial sites--has significance that cannot be ignored. Protesters argue that they were not consulted in the decision to reroute the pipeline, and that instead of negotiations, their rejection of the pipeline is being met with violence. The people I spoke to aren’t camped out at the reservation solely because they feel a special connection to the natural environment, and many who care about the environment would never dream of going to Standing Rock. The protesters are there because they’re tired of talking to a state that won’t listen. Only people who are exhausted by betrayals, unresponsive political processes, and a conspiracy of silence would be so dedicated to such a sustained act of protest.

This systemic exclusion is pushing Native Americans out of mainstream US politics. Only the Green Party campaigned on justice for Standing Rock, but when the most liberal-minded Democrats are determined to discredit outsider parties as “dividing the vote,” it is a kind of silencing, an act of violence. Furthermore, not a single question on climate change was posed during the presidential debates, to say nothing of other Native issues. But just because the system won’t see the issues doesn’t mean the issues aren’t there.

Brooke Lends-His-Horse, a thirty-year-old, visibly-pregnant protester, has been making the trip to and from Standing Rock with her two young children nearly every weekend since the protests began in April. She has been to the frontline but stopped going once state reprisals escalated and pepper spray became the norm. She brings her children, she says, “because I am doing this for them. I feel like I’m mourning a relative. But worse, because it will affect generations and generations if that pipeline is built.” Passionate, focused and dedicated to opposing a political issue that affects her--an ideal voter. Yet as passionate she is about this issue, she’s completely apathetic about the 2016 election. Like many other protesters, she considers herself a Democrat, more or less, but she can’t be bothered to vote this time around. She doesn’t believe that either political party cares about her or the things that move her.

At a purely instrumentalist level, no one expects a defense of Native American rights from Trump’s racist platform, even if respect for property rights should resonate with GOP principles. But the Democratic party is losing a key constituency in states that may have voted Republican in the past. Native American voters may not constitute a swing state electorate, but their votes matter and might make a difference in tightly contested races. Yet while everyone I met voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012, none plan to vote for the Democratic party in 2016. They believe that the president and the party have failed them.

“We saw him as the first Native in office, in some ways, because he seemed to really listen to us,” Kills-in-Sight tells me; “but now he won’t even get involved.” Obama has issued two statements on the protests that protesters see as lukewarm and non-committal. Despite his historic visit to Cannon Ball in 2014--only a few miles from the Oceti Sakowin Camp--the current president is now seen as part of the system that protects corporations over people.

Standing Rock is an indictment of corporate capture of the two-party system in the US at the cost of issue-driven politics and the real concerns of people, in this case Native Americans. The system that makes it possible during an election year to ignore the largest protest of an entire demographic in a hundred years is the same system that lets demagogues hijack the national discourse in the name of bloc voting. Voting blocs that are focused on gaining and defending power have little time for listening to real issues or speaking out in defense of the silenced, and the protesters at Standing Rock know this keenly. “They’re all in bed with the corporations,” one of the other men in our small group says, “that’s why they won’t bring it up. That’s why they don’t care.” And everyone who hears it agrees.