Chad Wys is not a thief. Or a vandal. Certainly, the Illinois-based artist relies heavily on appropriation, altering pre-existing prints and decorative objects. And there is an irreverence to these transformed works. In his latest Readymade series, Wys modifies reproductions of centuries-old portraits, obfuscating each sitter’s visage by painting over the source material, frame and all, often in shocking neon hues. In one piece, Sight Line, three-quarters of the original portrait are covered over in white paint. Only the subject’s eyes peer out, and viewers are left to guess at the nature of the sitter’s expression: the stare plaintive, the identity completely masked. In concealing much of the first image, Wys revises the work into a portrait of his own making.

These are not Duchamp’s readymades; it’s not the simple presentation of Wys’s found materials as works of art that makes them transcendent. But for Wys, there is a social and critical agenda to this practice: “Appropriation is the art world's answer to investigative journalism,” he says. Between applying steel nails, glitter, rope, rocks, and minerals to idyllic statues (sourced by scouring antique stores and estate sales), Wys stretches the limits of the genre, skewing our perception of these staid objects with sardonic wit. I spoke with him about the generation of new material from old, America’s inferior decorative impulses, and the reflexive nature of appropriation art.

Your works incorporate portraits and decorative objects that could easily be found among the clutter in secondhand shops. How do you come by your materials, and how often do you shift among media?

I often make trips to local thrift stores and garage sales. That pilgrimage, for me, is an important part of my process. The viewer doesn't see me traversing these places, but I try to impart some aspect of my journey with the titles I give some of my works, like Thrift Store Landscape With a Color Test, or Garage Sale Painting of Peasants With Bars. Simply indicating where the objects were found gives viewers an experiential narrative with which they might relate. Many of us know the experience of visiting a charity shop, and we know those places are inundated with objects that have mysterious former lives. I've always been interested in "used" objects; it has been somewhat natural for me to appropriate such things into my work.

As for changing mediums: I'm always changing, experimenting. Once in a while I might get into a rut where I focus heavily on one or two ideas, like collaging with paper or working on a computer, but those moments are fleeting, and soon I migrate to something else. I'm not satisfied with specialization, and I feel the need to diversify my output or risk growing creatively bankrupt.

How would you say your most recent series of readymades diverges from your past ones?

The readymades are essentially a single continuous series — that's how I view them anyway. They all speak to similar themes of materiality, historicism, and presence and absence.

In each round of readymades, you introduce different media — glitter, rope, and most recently nails and minerals — to apply to your source material of found ceramics. How do you select these items?

Most of my aesthetic decisions come about through experimentation with materials. There's an awful lot of trial and error involved — there's no right or wrong solution but a series of endless experiments that sometimes result in a work that I'm willing to share.

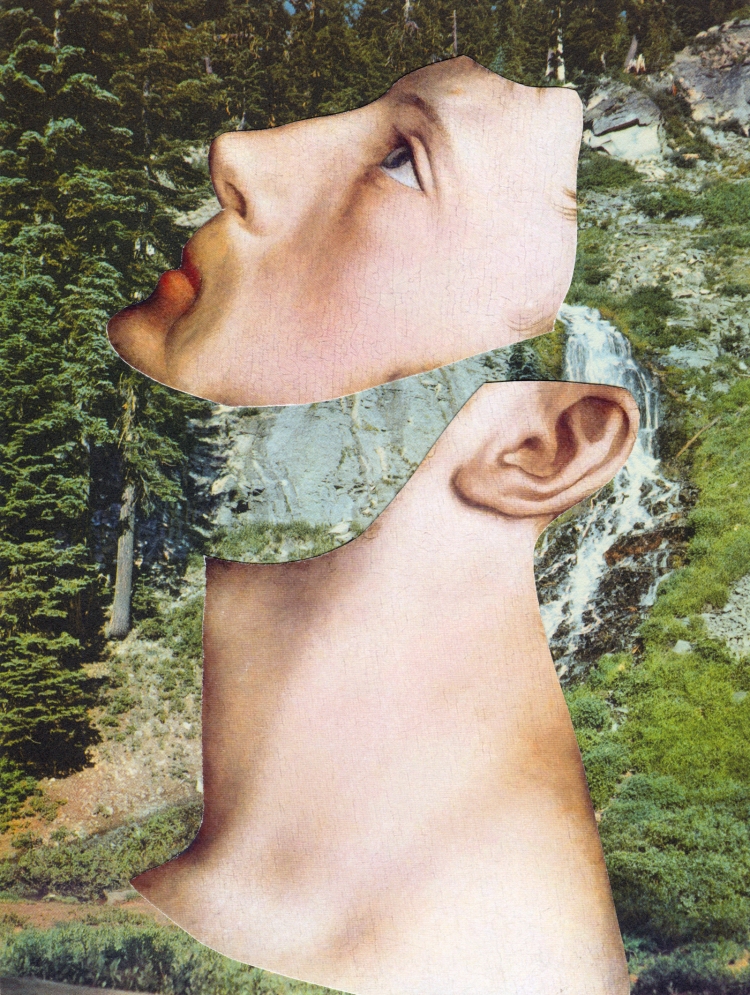

Why did you start toying with the limitations of portraits?

It's easy for us to relate to portraits. Where landscapes or still lifes can’t cause us to wonder what they're thinking, we look at a portrait and our minds run wild imagining what the sitter might be pondering. We wonder who the person in the picture really was and what they felt. I personally began to wonder about portraits as a convention in art and art history. What really is the portrait's purpose? Portraits normally communicate next to nothing about the sitter — really, we come away understanding more about the artist, and the decisions he or she has made in portraying the sitter, than the person being depicted. So what really are portraits for? Through my interference — by eliminating visual clarity in most cases — I'm primarily trying to engage the viewer in an internal dialogue about one's projections and one's reception of art and images in general, and potentially even how we receive other people.

Many of the appropriated figurines and portraits are reproductions of Renaissance and 18th century works. What’s the appeal of these epochs and styles, beyond simply being romantic and sort of long lost?

It has really just worked out that way. From the 1950s onward American decoration has embraced the aesthetic finery and artistry of those historical periods, so inferior vintage or contemporary reproductions frequently surface in the secondhand shops I visit. It's a curious juxtaposition: a crude, contemporary reproduction of an extremely fine 18th century German porcelain making an appearance at a Goodwill in Central Illinois (where I live and work). Americans have enjoyed having such inferior things embedded in their decor for decades. I can totally understand it: I admire those objects as well, and one's desire to possess them or to be near them is strong. So rather than buy the valuable originals, which most of us cannot afford, we acquire economic avatars, replicas, or simulacra. Part of me understands how tacky these reproductions are, and yet part of me finds them perversely wonderful and stimulating. Beauty is indiscriminate — it's found in higher and lower art forms alike. These conflicted feelings more or less become the point of my work.

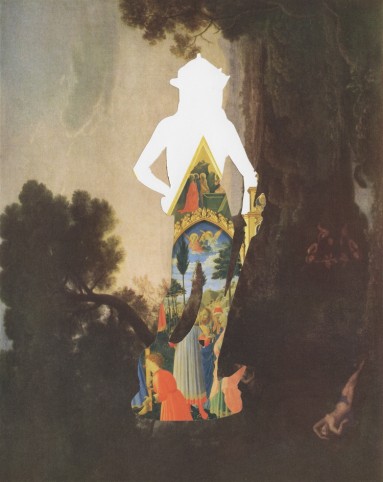

In Between Two Civilizations, from your latest Works on Paper series, we see a void where a figure once stood, half the body replaced by what looks like a cut-out from a medieval scene. Why merge these two specific works? What were the sources?

I acquire art books at various shops and sales, and I end up incorporating various images pulled from those pages in my paper-based collages. In the Between Two Civilizations collages I simply cut out a sculpture, flipped it upside down, and collaged it into another setting. I like the resultant ambiguity. I think it provokes some meditation on how images function together.

What is it about appropriation that seems to turn a critical lens to genre? What questions do you hope the viewers will ask themselves about, say, portraiture after seeing your images of muddled faces?

When we write an analytical essay about a given topic we're looking deeply at the subject of our investigation by citing and referring to the materials directly; when we write fiction we are inventing scenarios that can affect the reader. I think appropriation art is inherently critical, like writing an analytical essay; whereas I see most other art behaving like literary fiction. I'm offering up visual information taken from culture in an effort to evoke new discussion around various subjects that I think deserve critical examination, like art history or mass (re)production. I have no substantive expectations regarding the viewer of my work, so I can't speak to any specific questions I hope my audience asks themselves. I simply hope they see the found objects in a different light.