Charting the losses of contestable sickness

ILLNESS is a state of the body that demands testing.

April 26th: Self-testing/Reality-checking

I woke up one spring morning with vertigo. I turned my head to the window and nearly got sick on my pillow. I was 33. It is common for the newly vertiginous to distrust their perception of motion because vertigo is uncanny. The world is familiar, and yet the known spaces of your life (your room, your street, your workplace) are uninhabitable, because they are moving. Thus, the first round of testing is a self-directed series of questions: Did that happen? Did the room turn with me? (Yes; yes and no). This second answer with its relative “yes and no” is the pivotal point of the vertiginous person’s relation to their life and to the world. Because the room turned for me, but not for my partner next to me, I would have to see a doctor. And because every space continued to turn for me wherever I went, I would have to change my relation to the world, as regards what I could expect from it and it from me. Could I expect rest? food? comfort? Could the world expect adherence to its metered and measured environment? Independence? Labor? Seemingly esoteric questions critical to daily exigencies: could I eat, and could I work?

(I said the spaces of my life became uninhabitable; I continued to live in them because I continued to live but for a time in a way that felt like a lonely death. No one can follow you into vertigo, or into any sickness for that matter.)

May 1st: Wild Rose Vestibular Rehabilitation and Audiology Clinic

The first symptoms of my illness were tinnitus, hyperacusis (a rare condition of hearing sounds at painful volumes), and vertigo, and so Google told me my problem was otological (a word that autocorrects to ontological, which also feels appropriate). There are several ear conditions that cause spinning, which specialists can identify by tracking nystagmus, the abnormal beating of eyes as they follow objects. My mother took me to a vestibular therapist. I entered the clinic staggering, my arms reaching out in front of me for any wall, or chair, or countertop, to let me know where I was in the organized space of the room. A zombie in a vertigo nightmare. The therapist was surprised at my state. In medicine, you never want to look like something no one has ever seen before, something beyond evaluation that will not fit within the known universe of legible maladies and, especially, remedies.

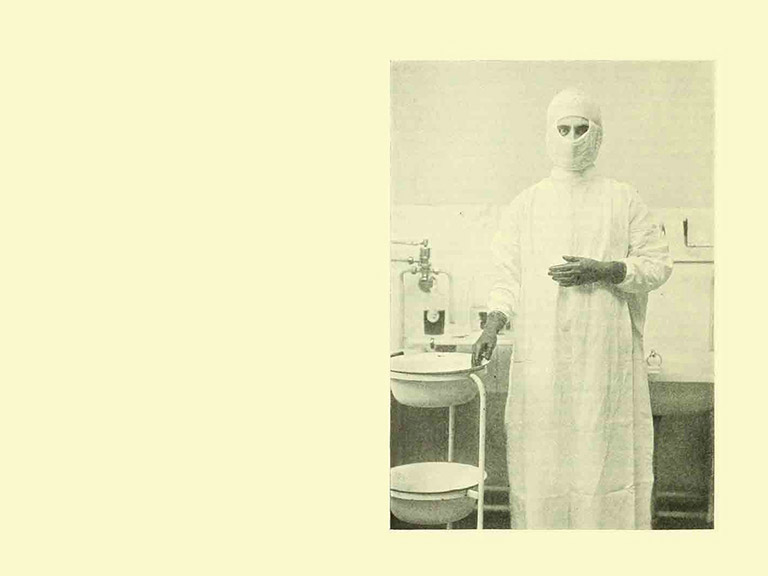

The vestibular test involved opaque goggles that project the eyes on two TV screens. I cried in protest at the darkness that I knew would accelerate the spinning. I reached my hand to hold the therapist’s arm -- uninvited skin on a stranger’s skin. She looked at my mother and my mother at her; which of them could explain my excess? Or this breach of social boundaries? Then I went and laid my head in the stranger’s lap. She said: “Listen to me. I once had vertigo too. And guess what? Last weekend I went skiing with my husband and my kids.” I wanted to throw up. But I allowed the darkness of the goggles because even that kind of alright-ness was desirable. The site behind the drawn curtain of the medical cubical was one of uneasy conjunction: all of those measuring apparatuses, and every space between them saturated with fear. When she fit the goggles to my face, I caught a glimpse of the left TV, there a giant eye flitted like a cornered animal, and I recognized my own horror.

(I was incapable of thought then, but remembering it now I think of Anne Boyer: “This is the problem of what-to-do-with-the-information-that-is-feeling.”)

“Her eye movements are irregular but not in a recognizable way. I’m not even sure if the distortion is coming from her ears or her brain.” -- a vestibular specialist.

The body that refuses the parameters of the medical test is an unlucky body. Especially because it means more, even unlimited, testing, more encounters with non-recognition, further alienation. But also because sadness, fear, and desperation are considered interference in clinical testing, and these emotions increase the longer a diagnosis is deferred. Affect is surplus without value.

There are several tests that every first-year medical student can use, and with fair accuracy, to determine the presence of a neurological disturbance in a patient. They are the finger-to-nose test, the heel-down-the-shin test, and the follow-the-pen test. There are non-invasive tests that will reveal with more precision the location of that neurological disturbance: the computerized axial topography scan, which can detect brain swelling and hemorrhaging, and the magnetic resonance image, which will light up tumors and lesions. There are invasive diagnostic tests that can more narrowly decide the cause and nature of a tumor or lesion: the lumbar puncture, which collects a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, and the biopsy, which extracts tissue for microscopic investigation. If the tumor or lesion is too deep for biopsy, such that a biopsy would cause damage to the brain, then there is one final test, non-invasive and barely medical, and that is time.

(I used to say damn it some one must tell me what is happening to me. I used to call sickness up to my every measurable surface with the incantation: Show yourself.)

May 9th: Medical Imaging Department, University of Alberta Hospital Multiplanar, multisequential MRI of brain with and without IV contrast

FINDINGS: T2/FLAIR bright lesion in the right middle cerebellar peduncle measuring 1.3 x 1.0 cm.

A lesion is any localized abnormality found on the body. Lesions are not particular to a disease or condition: they signal a structural difference from healthy tissue, nerves, etc. My lesion is in my brain, on my cerebellum. My lesion is too deep for biopsy. After this MRI, my diagnosis was brain cancer with a differential of multiple sclerosis.

Following some diagnoses, sadness, fear, and desperation continue to increase. For the moment, the doctor’s work is done, and emotions unfold in private interiors, among you and others near you, where they disrupt no one but yourself and these others near you. I tried to move around my home the way I had the day before. I tried to move as if I could feel the floor beneath me, and as if I could breathe that easy breath of the continuous life.

May 17th: Diagnostic Imaging, St. Mary’s Hospital MRI HEAD C-\

FINDINGS: solitary lesion in right middle cerebellar peduncle, could represent a demyelinating plaque.

Demyelinating plaques are the scleroses of multiple sclerosis, areas where the protective myelin that encases nerves is stripped away. After this MRI, my diagnosis was tentatively multiple sclerosis. Finding out that brain cancer is a misdiagnosis is at once a relief and a terror. The razor edge of life newly-granted balances just on the other side of a gaping death. How to live when you know how easy it is to die? It was not so much a misdiagnosis as a difference of opinion. The lesion in my brain is hunkered down deep, unavailable for biopsy, and so, in itself, gives no more information than the fact of its existence. Doctors have argued right in front of me, before a screen of my brain, the points for and against both tumor and plaque. (Some illnesses submit only to that final test, time).

“This is a difficult case.” -- my neurologist.

I wanted an etiology. Diagnostics and prognostics are future-orientated projects, optimistic in form if not in content. I wanted that dire course of my recent past, the charted points of my specific failure. I wanted an etiology general to the type of neurological event I experienced, but also specific to my personal life. What had my body done to itself? And when, exactly? What time was it when those changes in my brain became irrevocable? (When I fell sideways up the stairs on Tuesday? When I hugged the lap of a vestibular therapist instead of going to the ER?). There are no tests that can identify these moments, and these are not in fact medical questions. They are the existential crisis and the abjection of feeling, and then seeking, the fracture-line of meaning in a life.

(For a long time, I didn’t let myself remember anything from before. I stored a lifetime in the orbital bone around my right eye. The skin there became painful to the touch. This is the pain of non-recognition, I told myself. And it was.)

“The real question is, what will this look like in your life, practically speaking.” -- my insurance adjuster.

“MS is just a word, it doesn’t change who you are.” -- a different neurologist.

I disagree. But this is the nexus of insurance pragmatism (who you are is the same as what you can do), and brash medical optimism (illness affects what you can do only in so far as you let it).

While diagnostics are the test of illness, function is actually its truer measure. How much will you lose? What can you expect to be able to do around the house? At work? In the bathroom? And with what good humor, what positive attitude, will you confront the losses? For every functional loss, the medical industrial complex offers a mechanical, technological, pharmaceutical aid to replicate the function, which insurance adopts and identifies as the means of labor in illness. The sick person is responsible for availing herself of all of these accommodations. I have a bar in my shower so I don’t break my neck when I close my eyes. And that is about all the accommodation available to me. Yet the promise of medicine and the expectation of insurance is that I will find a way to reproduce all my functions, and myself.

(As if I could sit right back into myself. As if a self was an armchair. As if I wasn’t recast anew by illness. As if I had it all save for these isolated deficits.)

An insured body is a body that demands evidence.

My losses are both difficult to measure and to accommodate: chronic fatigue, chronic headaches, motion sickness, poor balance, tinnitus, hyperacusis, sadness, nostalgia, anger. The latter three are not in relation to loss of function. They hover over the outrages that are: the inexplicable, the past, and the eternal subject position of patient. The former kept me out of work, and qualified me, for a while, to a partial salary replacement through my work’s insurance plan.

The discourse of insurance shares interests with the discourse of medical testing: it is concerned with naming (secular baptisms), with categories, and with function, but insurance has fewer classifications -- payable and non-payable conditions -- and is interested only in function insofar as it relates to labor, and labor to paid work. Where medicine seeks results, positive proof, by which to name, authenticate, and file illness, insurance seeks negations. The first principle of insurance is the de-authentication of bodies, and the discovery of function where there is no health.

“How long can you keep your head up unassisted? How long can you read a screen before becoming nauseated? Have you attended acupuncture for the recommended 6 months?” -- my insurance adjuster.

Insurance banks on the wellness industry’s persuasive, and now fully internalized, imperative to maintain ourselves, to somehow counter deficits in function that are medical, social, or economic. (Wellness is a leveler). It says: supplement yourself until your awkward and angular disability becomes streamlined quick-stepping ability; until, in spite of your age, illness, children, or finances, you are as able as a young god who has never been sick or poor or pregnant or faltering, or any age but twenty or any color but golden.

Health insurance is a fitting figure for the neoliberal relation between wellness and money. The obvious relation between the two is that diligently minding your health will keep you well enough to stay in paid work, or to keep looking for paid work. But the lens of insurance tightens focus on the actual obligation to self-care as an act of compliance in this exchange. To receive benefits, the sick have constantly to prove their dedication to health, their sense of their own responsibility for recovery, to earn the insurance money they actually need to survive. It is too easy to forget that whatever compensation we get, either private or state, we have agreed to pay for in one way or another. We have bought it like every other thing.

Because it functions as part of the service economy, insurance is in the business of selling lifestyles. But insurance doesn’t pay the sick in health, if it pays at all. Because the product is money, insurance effectively sells the material ability to sustain your life, the lifestyle of being alive. The emails from the insurance adjuster were full of resources: organizations and websites dedicated to the management of diet, sleep, pain, relationships, stress, and general outlook on life. They recommend supplements, meditation, stretching, and saying yes to social engagements. It is a deft slight of hand; insurance’s identity as pure finance (money making money) is obfuscated, and self-care replaces money as the means of survival.

(Don’t weary of supplementing, of fighting, of therapy. Don’t let on that your one desire is not to reenter the competition.)

The adjuster gets a bonus when she helps someone get back on her feet. She was eager to find a diagnosis for me that fit within the company’s regulations of non-payable conditions (any condition with qualitative effects; any condition in which a measure of ability remains). And because I myself was in the fading twilight of believing that knowing more could mean feeling less, I went to a neurotology clinic in Toronto for a last round of testing.

August 12th: Hearing and Balance Centre, St. Michaels Hospital

The neurologist in Toronto sits me on a swivel chair before a room of medical interns. This one is a test for all of us. I stretch out my arms and look at my thumbs. He spins my chair.

“Eye movement normal or abnormal?”

“Abnormal!”

“Disturbance from ear or brain?”

“Brain!”

We all pass. But abnormal brain is not a diagnosis, nor is it new information. I undergo seven more tests, the data from which yet again evade a secure diagnosis but confirm the following: “The patient has a demyelinating plaque that involves the function of her cerebellum, which is readily evident in both her neurological history and the appropriate abnormalities on her neurological examination.”

My last visit is with a psychologist. I answer a questionnaire:

Do you ever think about past instances of vertigo and feel fear?

Yes.

How often do you worry about your vertigo returning?

Fairly often.

Do you feel anxious talking or thinking about vertigo?

Yes. Very.

I begin to cry, not like me, but maybe like I did as a child. The psychologist looks at me and I see I have become an informer for the wrong side. My affective response is not appropriate to the questionnaire. I drop tears on it. My face is hot and red above it. My body is full of the wrong kind of information. Not data. Not paper print out. The typed questions before me should not elicit this much sadness. It is the sadness of memory, the sadness of waiting, the sadness of testing, the sadness of never knowing. It is the sadness of illness.

The psychologist writes a prescription. “I want you to take this every day, in increasing doses until you feel one hundred percent better. Don’t stop increasing until you forget that any of this ever happened to you. Until you forget the word vertigo altogether.” His reaction to me is remarkable for a few reasons. He asked me no questions related to sadness and made a diagnosis based on the sight of my crying. But while paying attention to only my body’s visible reaction to the questionnaire, he also forgot my body. Chronic is that which continues. In this instance he has forgotten my lesion and its daily symptoms. I will never forget that this has happened to me, because it continues, returns, flares and eases and flares again. But his advice also relates to function. He thinks I am too sad to function, as if memory (which shares a certain form of repetition with the chronic) is keeping me from “living my life.”

(Why say, I won’t let this change me? Why not say, this is a small death? There are many deaths before the end.)

Two months after this, I lose my insurance on the grounds of an “unmanaged psychiatric illness.” The immeasurable and qualitative displays of affect that once obstructed the object of medical investigation become themselves the object, and finally the primary diagnosis, when run through the metrics of insurance. Losing health insurance to an unnamed mental state is a gothic, a spectral, a gnostic kind of sexism. Hysteria, nervousness, sadness. Neurological exams and MRIs -- literal pictures of illness -- are nothing against these feminized monoliths. I didn’t see it coming. Because the front end, the interface, of insurance operates as customer-service, my insurance adjuster never let on that she was gathering information for anything more than helping my case, finding me resources, keeping me covered. She called me by name. She called me at home. Insurance is the long con.

What is insurance but an incorporated wager against you?

It sounds counterintuitive; insurance always assumes the lesser risk. But the lesser risk is not illness -- the lesser risk is the contestable data of illness. A dismissal such as mine comes down to an easy gamble that has little to do with health, or even function: What does she have in her hand? Is it enough to overturn this ordinance?

(I lost the same game we are all losing.)

I can say that after everything I still don’t know what happened to me or what will happen. I know less about my body than ever. All that data, all those tests, all of my own Googling, and I will still never know if I am doing the right thing. I don’t know if I’m doing the right exercises, or eating the right foods. I don’t know if I bought the right shoes or painkiller or pillow. I don’t know. I don’t ask anymore either. With the lesion came an initial threat of cancer and death, and then the differential of multiple sclerosis and the prospect of immobility. For now, in that final and enduring test (time), I live beside, or within, or along a set of chronic symptoms, which, gathered together, have no medical precision, but exist in my body as the residuals of a neurological event that is either ongoing or not; that will either repeat itself or not; that will either kill me one day or not. I’ve spent the interim attending to losses not physical. Opening that safe of memory around my right orbital bone and letting out old bits now and then to look at, from a great distance.