I.

First, some definitions:

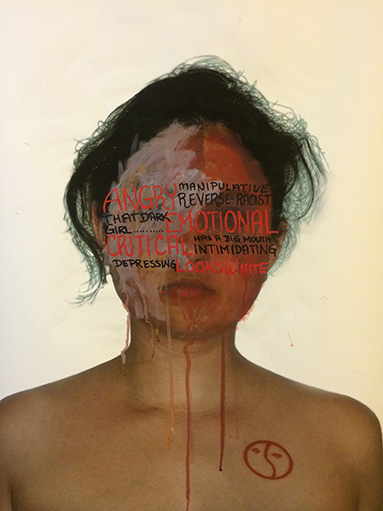

(White)spatiality: There is a specter here that haunts this space. It has multiple faces. We’ll call one white supremacy: the belief in the universal, a pure idea arrived at by a series of white men who have combed through culture and curated its worth. Another face we’ll call visual oppression. We’ll call it passing. We’ll call it presence without provocation. We’ll call it just enough black faces to assuage liberal guilt without the discomfort of challenging anything. We’ll call it the fantasy of postracial America. We’ll call it visible invisibility.

The Body of the Other: It goes where it pleases under the vague, ever-present threat of violence. It infiltrates. It wears the right clothes. It uses the right words. It has abandoned its mothers. But it claws at the ribs, crawls up the throat, and tumbles past the lips in polite company. Don’t forget what Gloria Anzaldua told us: “Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out.”

The Ritual of Looking: It is pleasant enough, the rapt masses examining objects, reading texts, staring at screens. It is pleasant enough, their whispered exchanges, the sidelong glances at fellow patrons. Like pilgrims, we circumambulate the rooms in near silent meditation, offering our attention to the gods that feel right to us. We want to say that there is a value in this thing we’ve been doing for thousands of years, this thing that’s been with us before capitalism, before agriculture, before patriarchy. This thing was there at the beginning: to make, to regard what is made.

White Aesthetics: And isn’t this specter the god of our neoliberal artistic landscape? A place where critical language—which is meant to articulate everything that is not said, to reveal the threads of systemic inequality—is co-opted by an inane buzzword pastiche? Where the artist-CEO employs the labor of others—material labor of unpaid assistants, affective labor of subject-bodies, contractual labor of the working class, temporary labor of performers, take your pick—to realize his unique vision? There is only space for “questions” here. Ambiguity is both a currency and a shield. The titillation of a brush with the radical—a safari of political rebellion—without the nuisance of actually addressing systems of power or challenging the status quo. All the trappings, none of the substance.

II.

Since 1932, the Whitney Biennial has promised its audiences a crib sheet for the market trends of contemporary art in the United States. Every two years, the Biennial anoints its debutants for the next round of museum trough feeding. Careers are ignited, financial introductions between artists and the wealthy are made, and Americans are re-educated as to what Art is supposed to mean in this country.

This is the Whitney Biennial for Angry Women.

Exiting the elevators on the fourth floor, we are confronted with curator Michelle Grabner’s statement, printed on the wall, and a portrait of Barack Obama by Dawoud Bey. Translation: “Look at art in the era of our first black president!” Alternate translation: “Thumbs up to the Democratic Party!” Another alternate translation: This is a signifier that links Grabner’s floor to liberal democracy—“Hey, I’m one of you, an American who believes in progress!” The biennial has three curators and each has a floor. Why shouldn’t they all have their own presidential portrait? George W. Bush for Anthony Elms. Eisenhower or Johnson for Stuart Comer. It’s safe to say that the Obama portrait is open code for the newest American myth: the multicultural, progressive future.

Obama as multicultural symbol establishes the “correct” gaze of the 4th floor and the 2014 Whitney. If museum goers were high-schoolers being forced to take standardized tests on imperial timelines, this symbol would represent the party line of contemporary American art. The insertion of people of color into white space doesn’t make it less colonial or more radical—that’s the rhetoric of imperialistic multiculturalism, a bullshit passé theory. What’s more, the 2014 Whitney Biennial didn’t even bother to insert more people of color. The gesture was merely rhetorical.

Rogue counting is finding numbers that institutions don’t want to produce, and we believe it’s essential to apply it to white curatorial practices. But the problem is structural, rooted in a long violent genealogy of gatekeeping. In the tradition of the Zapatistas, we talk back to the institution by translating its language. The following quotes are drawn from the curators’ introduction to the Biennial catalogue:

“We hope that our iteration of the Biennial will suggest the profoundly diverse and hybrid cultural identity of America today.”

Translation: “The 2014 Whitney Biennial is the whitest Biennial since 1993. Taking a cue from the corporate whitewashing of network television, high art embraces white supremacy under the rhetoric of multicultural necessity and diversity.”

“It became clear that we were inspired by a number of the same artists...”

Translation: “There are only so many white artists. You bump into the same ones again and again at parties.”

“If there is any central point of cohesion, it may be the slipperiness of authorship that threads through each of our programs.”

Translation: “We read Barthes’s ‘The Death of the Author’ in college and still cling to it as a justification for all of our specious curatorial practices. We don’t think about how it describes a cultural landscape rooted in white supremacy, where the positionality of the author is irrelevant. Questions of profit (i.e., who’s getting paid and who’s gaining power) will be conveniently ignored.”

“The exhibition and this catalogue offer a rare chance to look broadly at different types of work and various modes of working that can be called contemporary American art.”

Translation: “Our definition of different and broad is rooted in a definition of the art world that excludes the vast majority of the cultural production of people of color and others at the margins.”

“Some borders—formal, conceptual, geographic, temporal—get tested, but we can still see through the assembled projects and people how the breadth of art is expanding because it is the artist and makers themselves who are pushing boundaries by collaborating, using the materials of others, digging through archives, returning to supposedly forlorn materials, or refusing to neatly adhere to a medium or discipline.”

Translation: “Why can’t there be women abstract painters?” Why is this conversation happening? It’s so boring we’re falling asleep. Abstract expressionism is the expression of white male capitalist identity—why keep it alive? Let’s just decapitate the white male artists and dealers who believe this and be done with it.

The curatorial statement at the entrance to the fourth floor reads:

Donelle Woolford [Joe Scanlan] radically calls into question the very identity of the artist …

Translation: “Joe Scanlan is a white male professor from Yale who created a black female persona to promote his work, because he thinks that black bodies give their owners an unfair advantage on the art market. We are more comfortable with white fantasies of the other than examining lived experience. We don’t give a fuck about the history of blackface, carnival representations of the other, or violent displays of captured indigenous peoples as museum objects. We believe in our hearts that we are beyond this.

Translation: “What if we stopped searching for the implications of the white imagination and instead celebrated its racist and colonialist fantasies?”

III.

The white man understands everything better than you, okay? He will use fictional black female identities and then their bodies as props to help you understand cuz he’s afraid that if it comes from him, you might not pay attention. (I’m sorry, but this has never happened. Still, it’s good to know that this is his greatest fear.) #DominantCulturePersecutionComplex

He understands the world better. That’s why he’s the director, the manager, the CEO, okay? That’s why he is in charge of hiring, and we get to be hired, okay?! It’s just the way that things work. He comes up with the ideas. You get paid to play your part. Do you get paid royalties? Do you become credited in the company? Are you the artist? No. But that’s not the point. The point is that he showed us something old that looked like something new, and we must be grateful. Okay?

The manager, the director, and the CEO are neocolonialsts. He will help us understand that this is art. Diversification (i.e., the multicultural transnationalism of corporate enterprise) is beautiful to the white man director in charge of the spending accounts.

There is nothing wrong with him. There is only something wrong with you, the employee who refuses to submit to his gaze.

He will refuse his whiteness because he believes it’s possible to refuse our embodiments. He will cite a nonsensical theory about essentialism or Foucault. He will refuse his whiteness as if whiteness can be refused even as it’s constantly being affirmed.

“Donelle Woolford” is a fictional black female persona that Joe Scanlan invented and who now represents his body of work. In Scanlan’s narrative biography, Woolford was his assistant who made work from the scraps in his studio. Scanlan hires various black actresses to perform as Woolford in productions that he directs, as well as for artist talks at educational institutions across the country.

Scanlan has two paintings in the Whitney Biennial—Joke Painting (detumescence), 2013, and Detumescence, 2013—presented under Donelle Woolford’s name (she is listed in the catalogue as if she were a real person, with no mention of Scanlan). These dick joke paintings, the latest in “her” practice, are based on works by Richard Prince.” Scanlan has used his fictional black female character to appropriate from another white man. Bravo! White men continue to make art about their penises. Scanlan uses Donelle to camouflage his desire.

In Scanlan’s narrative, Donelle Woolford has the privileges of a white cis man without being one. She went on lavish vacations with her family. She went to a fancy school. For her BFA she went to an even fancier Ivy where she met all the right people. She’s had a slew of wonderful shows with powerful people. In Scanlan’s narrative she didn’t sit through critiques where her art was labeled as “not universal” because it contained her body. She didn’t deal with the sidelong glances from her peers, convinced the only reason she was even there was because she was a “minority.” She didn’t live the life of a thousand little cuts, the infiltrator’s life. She doesn’t know what it’s like because she is a figment of a white man’s imagination.

Scanlan didn’t look to lived experience or the political imaginations of Afrofuturism as a possible basis for his social fiction. Scanlan took the familiar life of a privileged white man and dumped its traits on an othered body. If only Scanlan could share the surface markings of your oppression—your skin color, your gender—but keep his foundational privilege, he could be a famous artist.

Because othered bodies are subcontractable and only that. They are sources of revenue—a perfect metaphor for the art world.

He will say that some black women didn’t mind, that they were paid, that it was okay. And he will say it over and over again, and you, dear consumer of the hodgepodge that is recycled and rebranded as culture—can you reject his repetition?

Actionable Responses:

1. Joe Scanlan wanted Donelle Woolford to perform at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which only shows works by artists of African descent or works inspired by black culture. The museum rejected his proposal. Whoever made that decision deserves an AWARD. Please contact us if you are interested in receiving an original sculpture and tributary poem.

2. We’ve coined the hashtag #scanlaning and launched an accompanying Tumblr (http://scanlaning.tumblr.com). We invite women of color and their allies to produce original “Joe Scanlans” (a.k.a. whiteboy art) to post online. We invite everyone to call out art-world racism with #scanlaning, to call out the privileged white aesthetic with #scanlaning, to call out white male fantasy with #scanlaning.

IV.

Dear White Curators,

1. Diversity is not the inclusion of those not from New York. Diversity isn’t more white women. Diversity isn’t safe art. Diversity isn’t black bodies put on display by white artists.

2. You don’t get to appropriate diversity as a buzzword for your PR work. Besides, we know how to count:

—There is one black female artist (we refuse to count your fictional black female artist)

—You put the two Puerto Ricans in the basement ...

—HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN is a collective of 38 mostly black & queer artists but barely gets treated as one artist. How amazing would it be if their 38 people counted as 38 people at the Whitney, which would accord them 40% of the museum’s space? They have been allotted an “evolving” temporary screening slot. They are the largest collective in the Biennial yet their real estate is virtually nonexistent.

—Gary Indiana, another white male artist trafficking in racist fantasies, receives more space, time and visibility than the 38 members of HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN

#tertiaryplacements #tertiarynarratives #tertiarybodies

3. Your theory is tired, your reasoning bland and your politics telling. To use Sara Ahmed’s term, your Biennial is a case study in “reproductive whiteness” – citation practices that privilege whiteness, white thinkers and white history to perpetuate whiteness. We know how to read between the lines.

4. Your choice to reproduce a whitewashed art world has material effects on the lived experiences of people of color and denies the shifts taking place in our visual world.

5. If you are interested in learning more about white supremacy operates in the art world see Pedro Velez’s ongoing public conversation: #drunkdictators #momumentsafari #AllYouArtEditorsareWhite #MonochromaticCritics #ProtestSigns #JamesCunonialism

Love and Kisses,

@clepsydras and @femme_couteau

P.S.

—After Jerry Garry Saltz’s praise for George W. Bush’s paintings, his approval is not a substantive career achievement. #irrelevant

—Scanlan has the same critical framework as Perez Hilton #manchild

—#solidarityisforwhitewomen

—#AngryPoC

V.

We’re tired of talking about them. We all know who they are. Let’s talk about us. Let’s talk about the people on the margins of things. Let’s talk about the ones who slip through.

Let’s talk about Etel Adnan.

In his catalogue essay, Stuart Comer points to Adnan’s work and the “nomadic, cosmopolitan patterns of her life” as the framework for his section of the exhibition. In her work he sees a kind of prescience. He sees “proto-screens” and “hybridity.” He attempts to mine the past in order to form a portrait of the present. Much has been made about the age of the artists in the 2014 Biennial relative to previous editions, and all three curators should be commended for reframing what it means to talk about the Now. But we are most seduced by Comer’s selection of Adnan. It is an assertion that we write new histories each time we make our work, that our histories are mutable, interconnected webs, not a linear progression of obvious genius. It is a nod to the periphery, to the unseen actors who shape our world.

In her leporello A Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut, Adnan takes us on an epic journey that sweeps through the individual, the political, and the cosmic with each brushstroke. Her prescience goes beyond form and medium as she constructs a narrative so rich with associations that it exists in the past, present, and future.

and we are the introverts of the space age

scratching clouds with closed fists

burying eyes in The leather of trees

eating and remaining hungry

kissing and remaining lonely

speaking and remaining doomed

breaking wells in the direction of death

This is the legacy of our civilization: No matter how far we move forward, we carry so many of the same fears. But Adnan offers us hope in the death of a cosmonaut, hope in our own mortality. The body suffers and then it dies, and those who are left behind will hold up the memory in space “which lingers between atom and dream.”

There is nothing new, just the old made new. This is our human legacy

Let’s talk about Dave McKenzie:

The Beautiful One Has Come does not mark itself as special—it is more dismissible than it is inviting. Dave McKenzie’s video is five minutes long and filters between two spaces: one a museum, one an abandoned building. One contains the bust of Nefertiti at the Neues Museum in Berlin, the other—the white noise of graffiti and broken windows. Both spaces are filled with objects we are not allowed to touch, signifiers we have lost access to. They are the objects of our imaginations—artifacts of ancient mythology and urban industrialization. McKenzie’s video shows the markings of these spaces, their capacity, their distance.

Each space is represented with a single take—with almost a direction transition between the gallery space and the abandonment. There are two moments where Nefertiti is clearly displayed. The rest are hurried shots of museum-goers looking at her. They watch her. They listen to stories about her. She remains in glass, looking elsewhere.

We are given more attention to the abandoned building than the museum. Here the camera floats. It is not hand held. It glides between the graffiti, the broken windows, the greenery outside. The spectator is moved slowly and there are no sounds of human interaction. We hear the outside but it is quieter than the museum.

The Beautiful One Has Come reveals the markings of space—how some are preserved and others are utterly destroyed. In the museum, the video performs a critical geography, becoming a quiet and constant protest of provenance, cultural privileging and beauty.

What is visible? What is invisible? What is at hand? What is hard to find?

We need to think about these questions and distinctions.

We need to think about taisha paggett.

Would the average viewer of the Whitney Biennial know that paggett was in the show? Probably not. Her name haunts the page of the museum guide, she is in “Other Locations.” “Other Locations” is tertiary placement such as: temporary screening schedules, “hallway galleries” and limited-run performances. But this is the Whitney Biennial for Angry Women. And we know she’s there, because we’re intimately familiar with Other Locations. We know she’s there because we set a fine-toothed comb to the catalogue to find her. We didn’t get to see her work in person. We didn’t get to stand with her, moving slowly, feeling our breath. But we can come to rest in her words on the page. To put it in her words, we can think about “a transhistorical, metaphysical her,” because when she talks through her words she speaks our lives back to us. We know this terrain, this terrain of the now. She is the beating heart of what we wish the Whitney was.

In the Biennial’s catalogue, paggett writes:

“also remember: the experience is not for me but for an us-ness that dies and comes alive depending on what we’re open to receiving, what interpretive frames we’re speaking to/from, and how deeply and consciously we’re breathing (the underseeing) as all of this is going down.”

This is the Whitney Biennial for Angry Women. In Other Locations: experiences for an us-ness that is both dead and alive. A demand for the impossible: decolonization, decentering, radical thinking, radical action, radical making.

Comments are closed.