Aging, as a staged theme, provokes other forms of performance to become strained and uncertain

“She was also an actress, which made the discussions of her even more real because she could be anything. She was a good actress, she was brilliant at pretense. She was more real in suspended disbelief than most things are just standing there. Her body, the one that you touch with your hands, unfolded into other people, and she was so sunk into performance that things got funneled into moments as hard as diamonds. The moments shimmered and hung in the air, they were at her fingertips, they were her craft.” —Eve Babitz, Eve’s Hollywood

“She was a great actress, but only in real life.” —Hilton Als, White Girls

THERE is a 30-second scene at the end of Quentin Tarantino’s 1997 revved-up blaxploitation film Jackie Brown where Ms. Brown (Pam Grier) is practicing. She’s practicing to brassily draw her gun, a firearm named a Colt Detective Special. With the gun carefully placed in an open desk drawer, easily reachable, Ms. Brown purses her lips three times, sometimes smiling, always grabbing the gun and pointing, punctuated by a sigh. In each sequence, part of a triptych, her left forearm is posed gracefully on the desk, in secretary-like fashion. She is bracing herself for what’s to come; she is staring beyond the camera. The eponymous heroine is a flight attendant for a crappy Mexican airline and, in conjunction with her lack of professional success, is often described as a “middle-aged woman,” struggling to get what’s hers.

This scene of doubled theatrics illustrates how in order for Ms. Brown to do her job, she has to play many roles and as many people. The audience has no access to the Real Jackie Brown (or Pam Grier, for that matter) but in the blurring of performance and performativity, theatre and reality, emerges the undecidability dwelling in the woman performer who is at the brink of becoming old. At the crux of this undecidability, this ambiguity of performance and rehearsal, is both a decomposition of what was once productive and a refusal to stick to the social script.

AS with pornography, Americans know a good show when they see it. But Myrtle Gordon (Gena Rowlands), the lead in director-actor John Cassavetes’s 1977 film Opening Night, wants to feel the performance as what it is: performance. A famous and serious actress, Myrtle is reluctantly starring in a Broadway play called The Second Woman, about an aging woman confronting the apparent hopelessness that will overtake the rest of her life. Mostly however, Myrtle, always with a cigarette at risk of falling from her open lips, is having an alcohol-ridden emotional-cum-professional breakdown in New Haven, where the rehearsals are taking place.

In the opening scene of its play-within-a-film, Myrtle’s character, Virginia (also Rowland’s name at birth), gets home late from the bar. She is confronted with a rather tedious diatribe by her onstage husband, a photographer named Maurice (John Cassavetes, also Rowland’s IRL husband), about the sins and virtues of “older people.” “I’m giving up [photographing] older people…can’t photograph them without their clothes on,” he says. Cue laughter — and yet he points to a prop photograph of a woman who looks like she’s in her eighties. Look how wise she is, he speculates. Women, as carriers of culture, develop wrinkles that tell fortunes. Wise old creatures… Myrtle as Myrtle will resist the trope. “Age isn’t interesting. Age is depressing. Age is dull. Age doesn’t have anything to do with anything,” she says.

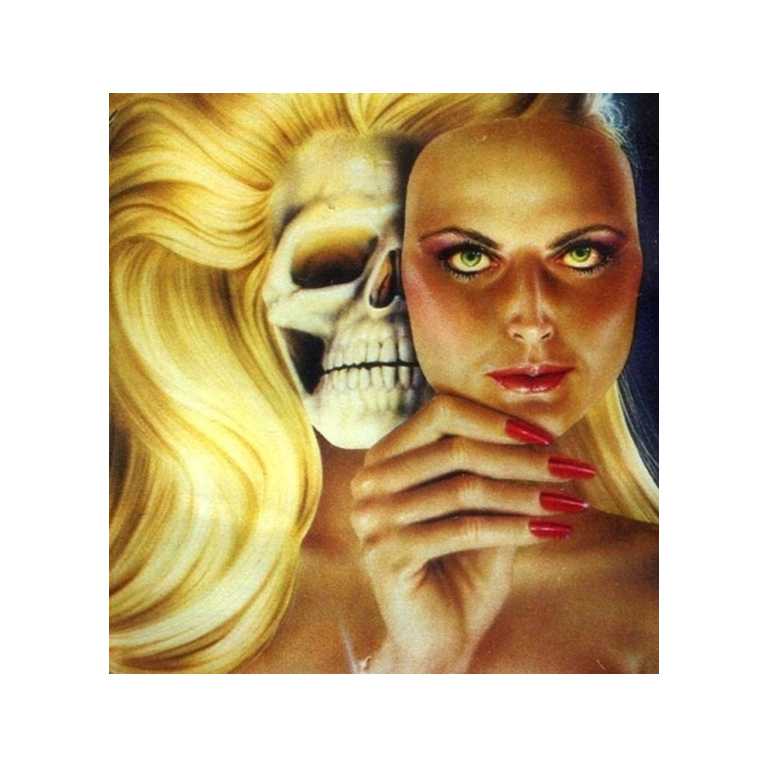

The deteriorating woman performer is a portable American figure: Take the recent Nina Simone documentary, or the 2015 film The Looking Glass. And 1950s Hollywood had Sunset Boulevard and All About Eve. These faded stars, these tragic heroines, give us the material to put off the assumed inevitable confrontation with our own dying bodies. We watch them to know them, to master them, to compare ourselves with them, to solidify our own experience. We see their crisis as one with age rather than a crisis propelled by socialized abjection. But these performers also displace our drive toward individual subjecthood in their fight with and against performance of what it means to “age gracefully,” which is often code for what it means to disappear. This dramatic confrontation with seeing the self as static image takes shape even amidst the very 21st-century idea of inclusion that all a woman needs to be is herself.

In Opening Night, an exhausted Myrtle Gordon is, as she says, “finding it harder and harder to stay in touch.” She connects this to her age, however loosely, comparing her current self to her teenage self whose emotions were on the bloodied surface. The film is grounded in the warrant that a woman lives out her life, if she makes it, in two stages, youth and old age. Moving through stages sets off not merely a loss of beauty and attention but, more interestingly, a decline of control over the power to perform.

Aging, as a staged theme, provokes other forms of performance to become strained and uncertain. But what marks this collapse into illegibility? What decides if she’s pulled it off or not? Who sees the crack?

Myrtle cracks in a watershed moment early in the film, after the death of a 17-year-old fan named Nancy. It is age, age as progressive and regressive, as stamping both time and loss, that names the downfall for Myrtle. After a show, Myrtle is signing autographs and saying hello to fans outside the theatre. Nancy stands out, even among the Belieber-like frenzy. “I love you I love you I love you,” she tells Myrtle. Nancy winces and falls to her knees. Though as a rule Myrtle is rather cynical about her fame, she gives in a little and gives Nancy an autograph. It starts pouring rain, and after Myrtle gets in her car and shuts the door, Nancy quivers in the pouring rain, petting the window with a soft yet terrifying cower. Myrtle watches for a few seconds — “something’s not quite right with that kid” — but now it’s really time for dinner, so they drive off. A minute later Nancy is hit by oncoming traffic. Despite Myrtle’s plea, the driver doesn’t turn around to see if she is okay. Death becomes her.

The enactment of gender, on and off-screen, is constitutive of social domination. “You’re not a woman to me anymore, you’re a professional,” spouts one of the many men with advice for Myrtle. But Myrtle — a drinker but still, as many drinkers are, a professional — feels too much and too hard the vulnerabilities of the stamp of woman. For one, she does not want to be slapped on stage. She’s not so much afraid of the slap itself so much as the making-corporeal of her gendered body on stage — it has the potential to cross that slippery ontological line between performing woman and being one. The play’s director, Manny Victor (Ben Gazzara) prefers, as men do, to make history of violence. “It’s tradition,” he tells Myrtle. “Actresses get slapped.” And inevitably, Virginia (or is it Myrtle?) gets stage-slapped (or is it really slapped?). She falls to the bright red-carpeted stage floor. Silence. She won’t get up. The camera pans to the small staff audience. She screams no, no more, no no no no. Someone in the audience claps. She’s still on the floor. Embedding the messy stuff of life within the hermetically sealed theatre, she derails the rehearsal.

It’s hard to tell for sure whether this is a politics of refusal or a failure to perform. “I seem to have lost the, uh... reality of, of the, uh… reality,” she stammers on stage in the aftermath of her fits. This undecidability throws the way aging is understood into crisis. Myrtle does not get up because she does not see what she calls “hope.” Yet by the cold bliss of her own inertia, Myrtle exudes a disinterest in aging as a theme even as everyone around her is telling her she can relate. Coupled with her visions of Nancy, Myrtle’s stasis amounts to a dissent to progressive temporality — which is part of why she was attracted to the stable narrative mores of the stage in the first place. The aging actress in Opening Night is not mostly concerned with keeping up sexualized appearances. What emerges as the ultimate unattainable thing is the loss of the illusion of performance. Myrtle does not want to become her role. She wants to play it.

A film rife with theatre metaphors yields little space to its actresses. What “woman” is is not divorced from the technologies of its representation if “woman” is, as Dai Jinhua argues, “always metaphoric,” or as Teresa de Lauretis has claimed, a “fictional construct” that also refers to “real historical beings” who are bound to those stories we tell. While “woman” always gestures out to “women,” the actress is singular. In Opening Night, we see Gena Rowlands negotiating a kind of double confinement. As the real and the performed cross-pollinate, the rhetorical only goes so far in giving us texture to life as we know it. Myrtle, who is not at all oblivious to her condition AS WHAT, boils it down throughout the film with Xacto-knife precision. For instance:

• “She’s very alien to me.”

• “I’m just so struck by the cruelty in this damn play.”

• “We must never forget that this is only a play.”

• “I accept my age... listen Sarah, every playwright writes a play about herself. You’ve written a play about aging — well, I’m not your age.”

• “I’m looking for a way to play this part where age doesn’t make any difference.”

• “Does she win or does she lose? That’s what I wanna know.”

Despite her poised, dead-smart script, Myrtle is a woman unhinged, deep in the makeup of her own life. In Cassavetes on Cassavetes, Cassavetes reflects on Myrtle’s struggle with the reality of clocked existence: “Sometimes I thought about [Myrtle] fighting and I would think, ‘Why doesn’t she just accept being a woman and be glad about it? Why doesn’t she stop asking herself all these questions?’ ” For Cassavetes, accepting being a woman is to accept old age.

Accepting being a woman? I hadn’t once thought of that. Power is never far from the mind — or the heart. There are better questions to ask if the answer to the banal ones are a depoliticized self-acceptance or the lukewarm inclusionary politics of representation. Questions like, Will she be able to act her way out of it? Is she acting or is this really her life? What does it take to pull it off? Why is age the only index that we don’t readily and happily call a social construction?

The notion that actresses are flowery, flagrant, bright creatures full of excess and digressions is a myth told in sexism’s name. After all, the art of show business is an art of balance: fully economical, no waste, no room for dallying around. Even improvisation is a theory of time, meter, calculation, and disciplined intuition. In a particularly pressing scene onstage during The Second Woman, Myrtle Gordon turns to the audience and says, “Time is a killer, isn’t it, folks?”

Myrtle has no stage problem, and she has yet to succumb to whether or not she as an age problem. She knows the rhythm of delivery. The audience adores her. This bleeding of script and heart anticipates the unfittingly happy ending. More applause. And yet the film is too raw and painful to be thoroughly optimistic. We are again like Myrtle. We don’t know if we’ve won or lost. We don’t know what is being performed.

In Figuring Age: Women, Bodies, Generations (1999), editor Kathleen Woodward is interested in how women become sequestered off from the world as they get older. (White women in general, like in the new Netflix series Grace and Frankie, stage a big fuss when they are no longer seen how they want to be seen.) Many of the shots of Myrtle capture a face at a slant. Eyes under a veil, figural fragments refracted in mirrors, head down, a mouth protected by a glass, eyes shielded by sunglasses, body doubled by Nancy. This body language is a kind of disinterest, a preference of madness and grief over accepting aging as only a matter of time.

Opening Night experiments with what Teresa de Lauretis calls “the conditions of visibility,” a far cry from the logics of making visible or being seen, which often forgets the possibility of the failed performance, the fucked-up, too-old actress on the verge, the one who hesitates to play her part because it is too close, too close to the role she cannot desire not to play.

Sontag argued that photography as a medium produces evidence. But film has the capacity to produce phantasm. Inasmuch as the moving image produces fantasy, it also positions desire. In an attempt to produce just conditions in an unjust world, it’s common to, say, quote Aaliyah’s debut album — released when she was fifteen years old — and say something like, age doesn’t matter. While Myrtle laments the loss of power — sexual, social, professional — that comes with aging, she can still make the ghosts “appear or disappear at any time.” Myrtle refuses the loss of all self-management but confronts the futility of privately having to confront a public problem: How boring is aging?!

Time is a killer because it is the merest trifle repeated over and over again. Naming aging as boredom is a response to the numbing effects of time. For Myrtle, boredom gets after the way time kills, even if boredom is a scapegoat for more illegible sensations. Myrtle is the woman who refuses to grow old because she refuses to grow bored.