Notes on opportunities blown and missed:

The Rise of the Planet of the Apes, 20th Century Fox

Conan the Barbarian, Lionsgate

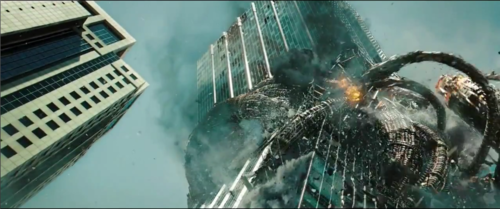

Transformers: Dark of the Moon, Paramount Pictures

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Miramax Pictures

This is one of two essays that constitute a loose, although non-sequential, pairing of reflections on popular film I watched in theaters this summer. This one is more concerned with issues falling roughly beneath the heading of “content.” The other essay, forthcoming in Mute, has more to do with a recurrent visual tendency: namely, the decomposition of large sphere-shaped objects or fields and the consequent snowing drift of debris, through which a few figures will make a slow passage. Preferably with their mouths open.

This has been a summer of blown opportunities, at least insofar as cinema allegedly devoted to taking those opportunities goes. There’s been a sheer blowing, one that evacuates any sense of weight that might mark a difference between one possibility or another: see here the hot glassy wind of irrelevant unmaking and particle effects that constitutes the relevant narrative arc of Transformers: Dark of the Moon. That at least knows how to puncture holes in everything, even if the holes are barely compelling and hardly ragged. At the least, it was both committedly awful and the source of one of 2011’s crowning moments of lolled-tongue stupefaction, as a giant chthonic robot worm, bristling with circulating razors, simultaneously encircled and penetrated Chicago’s Hudson Tower. It strangled it in two, like a burrowing python or chrome bolas, while characters inside shouted a lot and dodged sliding office furniture.

More though, there were opportunities that simply did not come. And if they did, they were resolutely shoved aside. See, for example, nearly the entirety of the new Conan The Barbarian. I saw it all wrong, perhaps: sober as sand, at early dusk with the sun still hazy outside, in the mood for something that understood pleasure. But all began well. Its properly exploitative first minutes gave precisely what we didn’t have: a particularly giddy, bright drunk of motion and axes. For those minutes feature — in rapid succession — a battlefield birth by C-section, a young boy hacking off a few heads while keeping a raw egg unbroken in his mouth, and an excruciating aria of hack symbolism regarding how steel needs both fireand ice.

Another tendency shaping recent mainstream film is the obsessive’s need to over-explain, to both show and tell, and to do both at extreme length: if one can use the 1982 Conan to help gauge the further banalization of pop cinema, then consider the difference between the two sword-forging scenes. The version from two decades ago seems nearly elegant, Bresson-ish, in its old-fashioned reliance on images and semi-deft editing to show the process. In comparison, that is, to Ron Perlman in barbarian/bear disguise explaining how steel must be tempered with fire and ice at the same time, while in the same screen time we watch a sword get dipped in a trough of fire and ice. In case we missed the point, immediately following, he tells young Conan that he has too much fire and not enough ice. As this occurs, he knocks him — because he’s too fiery, see? — into a frozen lake. It’s fair to assume that one or the other — the laborious explanation or the hammy diagesis — would have been plenty. Instead, the film, and we with it, groans beneath the weight.

Exploitation films are, taken generally, those that fully enact generic modes, premises, or single concerns (cannibalism, sex, motorcycles, samurai, werewolves, gladiators, pimps, a combination of all seven) and make of the attendant contradictions not a damning incoherence but a true joy and technics. Their massification is by now an old story, as we’re in the midst of a long stretch of years when films costing $90 million try their damnedest to necromance some of the lost aura of films that either “didn’t know better” or didn’t have the capital to do anything about it otherwise. Conan is one such film. It reloads a cult classic and marks itself as an especially pulpy incarnation of a diffuse lineage that runs through Italian peplum, sword & sorcery tales, D&D thrown into a creatine lab vat with MMA and parkour, and a distinctly ’80s version of the fantasy aesthetic that features a lot of big biceps and bigger hair.

Yet while Conan bares its beefcake, splatter, and consummate idiocy, it nevertheless botches nearly every instance it could actually exploit. It hacks its ankles out from beneath itself, and the resultant blood sprays no noteworthy patterns. Case in point: The story revolves around the reconstruction of an evil mask, at once antlerish and tentacular, with which our evil warlord can resurrect his evil dead wife and proceed to rule, evilly. And indeed, he collects the requisite pieces and prepares dark dominion. What, then, is the result, when he dons the all-powerful relic at the veritable climax of the film? The mask wiggles its limp tentacles a bit. That is all.

This is action-fantasy film fundamentally structured as mediocre straight porn: a hunk of male flesh tries to stay center screen while doing hypermasculine things for a prescribed duration of time, with the promise that the ending will be big, messy, and somehow related to the previous buildup. But Conan can’t even allow the highly limited pleasures of that. We’re left then, not with pulped froth but with turgid misogynist melodrama of the variety that spends a whole lot of time talking about what people would like to do to one another while constantly restraining that from ever coming to pass. For a film that gestures toward necrophilia, incest, pec oiling, and shapeshifting, it ultimately delivers one genuinely kinky moment (young Conan watching his father’s face get splattered with “molten sword”), plenty of stabbings, one brief hetero sex scene — of the blurry genital-obscuring-objects-in-the-foreground 1984 Cinemax variety — and a good 30 minutes of lamentations about a dead father. (1)

(1) If it is the task of a critic to say whether or not a reader should spend money and see a film, then I would say: you should not see this film. But if that is the task of a critic, as it may well be, then I am not a critic and may never be.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes comes closer to throwing open the libidinal floodgates. I, for one, cannot disavow the particular corner of the spectacle that involves apes outflanking the San Francisco Police Department on the Golden Gate bridge and getting away with it. But it’s there on that foggy bridge that the film works itself up to the moment for which we’ve waited, the truth of the film: A gorilla pins a riot cop to the ground, finally about to do with those big canines what big primates are good at doing. He is going to tear the throat from an officer of the law. But no. Caesar, leader of the ape insurrection, yet still tortured about the sanctity of human life because James Franco is very kind and has that smile, stops him as if to say, No, we don’t do that. We don’t kill. And if we do, we only kill in that bloodless way favored by films trying to keep their MPAA ratings down. Encourage them to crash their cars à la Blues Brothers, bring about mayhem in which other objects are technically responsible, let gravity drag them off a bridge, or throw multiple things toward them such that they are “knocked out,” much as PG-13 katana fights involve an excess of smacking enemies on the head with the handle. But kill? With hands, with mouths? No, no.

And so the gorilla merely roars at the cop. He has his species-enemy pinned to ground, and he yells at him. Yes, it’s a given that censors, studios, and a fair number of audiences will not permit any depiction of violence against the police that would — because it will — excite spectators: Such is one of the few remaining permanent taboos in mainstream cinema, roughly on par with onscreen pedophilia.

But the film goes to baroque lengths to bring itself to that occasion, to hint a path between the thick fang and the thumping bare neck. It goes even further to refuse to actually draw that crimson line. If one wants to venture a reading of the ideological bent of this film (a small frenzy of which have circulated), it shouldn’t lie in the particular modulations of the apes, in what they say, in how they are anthropomorphized, racialized, or gendered, in the fact that their leader holds up a bundle of sticks to make a fasces point about solidarity. It won’t be found in periodizing the differences between this remake and the previous incarnations. It doesn’t reside in the battle with the police as such or that the furry subaltern speaks, uttering the master’s language (“No!” – a snarkily proper choice of word if you’re going to hijack “the language of the Father”) as the marker of the uprising’s start.

And above all, it won’t be found in the obvious point that it is, nominally and substantively, a film “about” insurrection, that takes rising up (“ape-rising”) as its content and arc. What is relevant lies only in the forms into which this chunk of time is poured (2) and in this restraint and withholding, in the violence that does not happen, the limits that it imposes on itself, as it still polices its own actions once police are incapacitated. (The film’s tagline “Evolution becomes revolution” should actually read “Evolution becomes revolution becomes managed social democracy.”) And more than this, it is independent of the specificity of violence, its agents or targets. For the form of denial is the real content at hand. Turning back when the time is right, denouncing that possibility of exploiting the one true possibility built slow over an hour and a half and longer, over a century, the long history of cinematic memory exploited to make such a moment hang before us and not come off. There are no lessons to be learned here: There is only the dulling danger of lessons imposed.

Still, such films are blockbusters through and through, and one might say that to even approach that unfinished finishing move is really something for poppier entertainment. But adjudicating a general realm of what may or may not be possible “in mainstream culture” is not, and cannot be, a generative game for thought. It leads only to a sloppy balance sheet of what we already knew about the strict logic of profits, the infrequent exceptions to that, and the very frequent recuperation of those exceptions. As such, we’re infinitely more likely to see and say something compelling if we begin with particular films, their specific sets of proffered expectations and follow-throughs, their store of inherited moves, and their peculiar restrictions.

Joyous a sight as it would be, we’re not surprised that He’s Just Not That Into You lacked a significant quantity of jump cuts, nine-minute tracking shots over gray Romanian villages, neo-Expressionist set design, or an unstoppable plague ravaging Baltimore. To ask after them is a counterfactual dead end fated to pile up against the same wall. It wasn’t that kind of film because there was no way that it could have been. It would not have been the same film it was had any of those elements been present, hence the question asks only: Why is there not another film that exists? However, there are films that shape and code themselves, and are shaped and coded by producers, distributors, and marketers, as being ones in which just those sort of things happen. As such, what is worth asking after, not just with cinema but toward all cultural productions, are the highly particular exceptions, slippages, surges, fuck-ups, or, most peculiar and rare, flawless functionings of a film in terms of the relations — economic, generic, stylistic, and social — according to which it came to be and without which it simply wouldn’t be.

(2) See my forthcoming piece in Mute on this other side of the equation.

Of the films that cost a lot to make and that I spent money to see this summer, the remake of 1973’s Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark goes the furthest in blowing its chances. Although technically directed by someone named Troy Nixey (a comic-book artist and director of a short film that is pretty much Hostel with a heavy dose of monogamy and keys instead of humans), it is “presented” by, and intended to fall beneath the name of, Guillermo Del Toro. If anything, it represents the full extension of Del Toro into a discernible franchise and banner, complete with discernible — and requisite — tendencies, going so far as to provide the second Del Toro film in the space of three years to feature small, swarming “tooth fairies,” however wingless and furry they may be in this iteration.

In casual terms, I’m a fan of Del Toro. I’ve always lacked the subjective structure of a real fanboy and hence that specific relationship remains opaque to me. When it comes to thinking about films, shot angles, directors, cinematographers, themes, formal techniques, genres, characters, and so forth, there are those that I love fully, those that are “comrades” in how they articulate a similar loathing of the world order (yes, a camera angle or editing pattern can be a comrade or an enemy), those that exert a perverse fascination, and those that matter not a whit to me.

The last of these is a large group. The “Del Toro film” –- the whole swarm that goes by his name and which certainly includes him as a distinct writer and director -– fits into none of these. Quite simply, I dig them, and less simply, I take them as a sometimes fellow traveler to whatever swarm makes up my own thinking, watching, and writing. More specifically, aside from our shared interest in monsters, certain genres, and teeth, Del Toro is a sharp and funny man who, importantly, actually loves this stuff. (And he seems to love in the crucial way that such a love doesn’t make one a sycophant of one’s own taste but rather attentive to its histories, its offshoots and modulations.) Besides, he is part of that tradition that’s into “showing the monster” –- as he put it once, trying to avoid the tendency of bad erotic fiction to “call a sword that which is not a sword” -– and, better, which understands that “the monster” is not a vivisection as such, nor is it necessarily something that vivisects.

This is perhaps an unnecessary caveat, especially as I have little interest in taking films or their producers, directors, camera operators, sound editors or actors “to task” via critiques that will not remotely affect their practice. (We’ll be harder on them when we squat their mansions in Malibu or hack Regal’s digital projectors to replace their films with those of Jia Zhangke or Ida Lupino. Until that more material critique, there’s literally no point in saying, Roland Emmerich, the people have spoken: That pixelated blood is on your hands!) Therefore, if we aren’t talking a practical theorization of what, how, and with whom we want to watch without having to route it through the sham agora of the megaplex, then critique and theory will be addressed to ourselves.

As such, we might begin with that outer layer of “our side” of the circuit: official reviewers who, for the most part, are merely the industry as such in front of a not particularly dark mirror, mouthing the words already spoken, adding adjectives, mentioning who performs admirably, shitting on the films there to be shat upon. Without getting into the minor modulations of opinion or their final judgments of the film, one thing becomes quickly evident: the limits of the striptease or porno understanding of cinema, however pertinent it may be to such films as Conan. For in the case of Don’t Be Afraid, a lot of the reviews seem concerned with showing “it” –- that is, the monster, the small ape-fairies out to tear the teeth from the mouth of children –- too soon (“the haunted-house-style story is hampered by his desire to show them off”) or not showing it soon enough (“What they’re after is clear from the film’s gruesome prologue; what they look like is withheld until long after we have ceased to care”). If we need further evidence of the commonness of this erotic spectacle understanding of film, Roger Ebert is, as always, very good at accidentally laying bare what’s beneath how we figure our responses: “This is a very good haunted-house film. It milks our frustration deliciously.” (3)

But whether the milking of Ebert’s frustration is delicious or not, what no review will fully touch is another question, insofar as reviews are concerned with the degree to which films are adequate to the expectations mutually agreed upon –- the kinosocial contract of sorts -– through individual life spans of film watching and a messy century of global film production. At times, reviews can be wowed by what “exceeds our expectations” or is “better than we could have imagined.” And we are all equally familiar with the tired or worried invectives: “X film is staggeringly stupid, and it therefore assumes a stupid audience — my god let that not be true, at least not to the level decreed by Cats and Dogs 2: The Revenge of Kitty Galore”; “X film indicates a trend line according to which popular cinema is getting worse and more concerned with Taylor Lautner sliding down the side of a glass building than with building up convincing characters.”

As for the first concern, yes, we are that stupid. As for the second, just because The Ipcress File is a smart and subtle film does not indicate anything about the 230 nominally similar films from 1965 that did not see the light of day again until torrent hunters started sharing them. Many of them are neither smart nor subtle, and they may be remarkably good for precisely that reason. Apply that logic of selective canonization to now, and the historical judgment becomes far trickier.

The line of thought worth pursuing, to flee the delimited zone of the review, is not the success with which we get shown what we came to see, but the extreme restriction of what it is we may have come for, all the more in the films that trumpet their capacity to do this. As we said, applying this in general is not compelling. However, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is a film about imagination, and not just as its subject matter. It passes a subjectless judgment on what constitutes the inventive and spooky, from that Proustian magic lantern revolving in the little girl’s room to the hissing voices that come through the heating system, from what they will do if and when they get their hands on the kid to what it means to be a fucked-up family. It firmly inscribes itself within a couple traditions of horror. First, there is the “fantastic” Del Toro world, the love child of a Dungeon Master’s bestiary and Erice’s Spirit of the Beehive, equal parts lovingly hand-detailed carapaces and sad-eyed dark-haired adolescent girls (here named Sally) tempted to flee their familial and political situation for something more magical. Second, especially in this film, there is a gesture to “weird” horror much in the way that Tarantino gestures to Monte Hellman in Deathproof: they talk explicitly about Arthur Machen (during the requisite trip to the archive), and the house belonged to “Emerson Blackwood” (read: Algernon Blackwood). Machen and Blackwood are major figures in the history of English-language horror literature, both prolific writers in the early 20th century.

But more interesting, the film’s background subject matter -– architecture and design –- finds itself doubled in the relation of the film to the haunted-house movie and other lineages to which it aims to hearken back. Because, after all, the grounding narrative at hand is one of “restoration”: a self-impressed architect (Alex, played by Guy Pearce) has sunk his money into restoring the manor, with his interior designer girlfriend (Kim, played by Katie Holmes), of an artist-naturalist (Blackwood) so that he can get on the cover of an architectural magazine and sell the house to someone for a lot more money.

The entire concern, then, from the diagetic world to that of the film as a whole, is: How does one restore what has gone to shit, decayed, or been forgotten? Of course, the operative cinematic fantasy is that the very act of restoration is capable of unearthing some of the magic, however murderous, that was once there, as if the sheer fact of labor and refinishing will crank up the old generic engines and let the nasties loose once more. Yet there is another aspect of restoration present, and it is interior design: not architecture as such, not the design and construction of forms, but the redressing, repolishing, and regilding of given surfaces in accordance with an enormous set of internal restrictions about fidelity to the original, all to produce the illusion of it never having changed in the first place. An enormous investment of time, money, judgment, and intellect is poured into the erasure of time’s passage. The wager is that you can add new stone from the old quarry, and it can mean what it meant to those who ran, laughed, looked, painted, and died on and beneath that stone. The house itself is, like its film, a remake.

It might be seen as rather unfair to attack the Del Toro enterprise. After all, as things go in popular cinema, he is “on our side”: not politically, but as mentioned, in that his name marks an actual care for these things, and those things are, more often than not, monsters climbing from a gaping hole who are certainly more compelling to stare at than Sarah Jessica Parker’s yawning maw. Shouldn’t we celebrate a film like this for at least making a move in the right direction and focus our real negative energy on popular cinema that is immediately “objectionable”? Isn’t this a bit like slapping the hand that feeds you, even if the food isn’t quite as good as it could be?

No. One should always slap the hand that holds out food and, at the last minute, replaces it with Katie Holmes, some loud noise, and an ending that is exactly calculated to be just the right balance of eerie yet still sentimental. Such that the child is indeed finally capable of expressing her love for the surrogate mother and the surrogate mother can be slightly creepy yet without constituting a threat to the family tricycle composed with her as the necessarily absent third wheel.

Because this is not an imaginative film, even if it is about imagination. It is not a film that revels in exploitation, in seeing what can be done with the chances it proposes. It reveals dully instead, not with the long Lewton withholding of the monster but in mobilizing that showing of the fairies as a blind to occlude a follow-through that might actually have been worth watching. That is, much as critics took the bait of laying their praise or dejection solely on the chronometrics of when we get to see the furry beasts, what is forgotten is that this mode of appearance is a real hiding. A battering of chance. The very category of judgment itself is rendered identical to the internal aesthetic judgments of the film: Will we see them, will they come at the right time, and will they look decent? But for a film that claims to be worth being seen because it arrives under the sign of inventive and imaginative cinema, a cinema that enacts a restoration in order to polish some sharp corners not seen for many years: For that we can indeed say, Seriously, is that all? And we will not be saying that to the film. We will be saying it to ourselves, in the dark, in distraction’s half-light.

For like the films with which I began, what emerges in the place of a film really gunning it and actually letting itself be what it trumpets (that is, spooky, weird, unsettling) rather than what it involves (that is, hissing voices saying, Come play with us… in a supposedly creepy way for the 1,284th time in horror film), is again that intolerable, eternal restraint. To take one example, the fairies let themselves get sabotaged by allowing Daddy and Future Step-mommy to live long enough, because, just like Caesar urged the gorilla, No, we don’t do that sort of thing, we just knock them out, even though we have plenty of knives and we have tried to kill before. It is further dressed up with the camouflage of arcane “rules” to be followed, such as the claim that the fairies only take one child per generation.

Of course, the film does not remark upon how its own rules are entirely incoherent: the film opens with the previous owner Emerson Blackwood searching out more teeth for the fairies immediately after they have just taken his son. Nor does it let this rulebreaking devolve into a chaotic glee or darker negotiation: Imagine a version with teeth, so to speak, in which Alex kidnaps someone else’s daughter (or simply tears the teeth from her mouth) to feed to the fairies, to bind them to the pact, and therefore to leave his own daughter untouched. No such luck.

(3) He’s also increasingly good at dropping idiosyncratic/hallucinatory speculations in the midst of otherwise straightforward reviews: “You wonder how long life can be sustained on an all-teeth diet. Now that Bill Clinton is a vegan, let him try that for a while.” Yes, I suppose we do wonder that. But why Bill Clinton, and in what way are teeth vegan? Consuming nothing but the part of the body that another creature uses to consume food is one of the more strikingly un-vegan things imaginable.

The point, of course, is not to say, Dear Hollywood, stop making these films. They are inadequate! It is only to use these inadequacies to illumine and texture our own. And in this case, the very uselessness of such an injunction to make different renders clear the absent conditions in which it would make a grain of sense to say that. That is, if we had the capacity to

1) Make the kind of films we want to watch (including ones that involve small hairy fairies storming across 19th century carpet as if the Winter Palace lawn to tear the pearly whites from the skull of an asshole architect who also happens to be Guy Pearce. And no, I don’t think that desire is limited to a retroactive creation based on “that is what is available to us,” because it isn’t, other than as a deferred moment).

2) Shift what it is we want to get out of the cinema. (I, for one, think it will be a long time before I lose the desire to see those teeth pulled from thatskull. I cannot possibly be alone in this.)

3) Impose our will on Hollywood. (We force Paramount to permanently defund and publicly lash Tom Dey for Marmaduke. Michael Bay directsTransformers 4 with handheld camera, a hacked copy of iMovie 6, an amateur cast, and a strict adherence to Dogma 95 rules, all at gunpoint. Wes Anderson is “strongly urged” to remake La Terra Trema in black-and-white with an all-Limp Bizkit soundtrack.)

Sad as it is to say, the realization of any of these capacities seems a long way off. The first involves, to a certain degree, a flight into other media. Certain things can be done more cheaply and otherwise, via the much-touted capacity to shoot and edit digital video. But the very fetishization of that carries a whiff of redescribing necessity under the guise of petty rebellious freedom: Yes, we can pull a lot off without the studio apparatus, but that indexes all the more the gap between the effects one is capable of producing.

Such misprision is largely the point of that insufferable piece of tripe called Super 8, that pretends to celebrate amateur efforts (ah, nostalgia for kids just making movies, not for money but love, wide-eyed!) while declaring them utterly inadequate through the material fact of its cool $50 million budget. It’s for this reason that a simultaneous celebration of what cinema can do with a renunciation of continuing to put up with the Hollywood circuit may involve, above all, a double flight into other media and into other subject matter. It is extraordinarily costly to film tentacles erupting from the earth and reaching across the universe to wrestle the sun. It is very cheap to write that, although of course, the grammar of film and the grammar of prose will never be the same thing. It is also cheap to film a conversation between two people. The continuing disaster of capital may involve an increasing reallocation of modes and figures of thought to media capable of being adequate to them. A cinema adequate to its time and insistent on not remaining as such may now be one that doesn’t bother trying to “depict” the end of the world or anything so grandiose. It may burrow into its impoverishment and see what it locates there.

That’s a grayer possibility, but it arises out of the greater impossibility of the third option mentioned above. The mode of social upheaval building in the U.S will bear no possible resemblance to certain moments of the last century, in which the development of a socialist hierarchy complete with Commissars of Culture and centralized cinematic planning was occasionally plausible. This does not mean, however, that we should flee from the thought of intervening into the circuits of reproduction that both subtend and are generated by Hollywood, taken in its widest sense. We have as much say about the economy as we do about the cinema, which is and always has been part of the economy. In both cases, we relate to it as one relates to an earthquake: You can shift your weight, but the disturbances of plate tectonics are the consequences of a set of tensions, relations, and drifts that entirely dwarf any illusions we might have about consumer choice.

Yet this is not to say that interference — not with “the economy” or “the cinema” as such, but the social relations on which they turn and which they reproduce — on all fronts has ever been beyond our reach. Its modes of transmission and dispersal are indeed not reducible to any single instance (a film, a cinematheque, a production company), but any critique that won’t take on the material occasions in front of it is not critique: It is just cowardice and obfuscation. A megaplex is as flammable as a mortgage office. Not to mention, it may well be a space more worth saving, at least until they cut the power.

The second option – change what we want to get out of the cinema – seems at both a long shot and a feeble solution. After all, you don’t choose your desires as you might choose an adventure. And moreover, the very notion that we just need to “think differently” about how we relate to that leviathan of capital called the culture industry smacks of those terrible notions of “prosumerism,” making sustainable choices, or, worse, “raising consciousness” without razing material edifies, as though it had ever been possible to substantively alter general structures of thought separately from the transformation of daily conditions. As such, a full version of this –- the transformation of wanting itself -– seems to require the fulfillment of those other two conditions: the full takeover of cinematic productive capacities by ourselves necessarily indicates the coming to a head of the kind of social chaos in which it might be possible to guarantee that other version of Transformers 4 gets made.

However, there is another sense to it, one that does have to do with a present relation. The questions behind these notes are those of negation: How do we negate without simply destroying or turning away from? How do we go to the movies without thinking either that they matter or that they are irrelevant? How do we do so together, rather than before the baleful dusk of a laptop? How do you wreck slowly, persistently, pointedly, with the double awareness that the effects won’t be seen quickly and that they will never be seen if they aren’t constantly, diligently, furiously enacted?

I have no general answer for these questions, as we shouldn’t. For negation is at once a care for and an equally attentive loathing of the concrete, a fine-grained attention to peculiar cases and an attack on how the general freezes itself in the guise of the particular. And so let me speak only of this particular Del Toro film, of the limits it points up. Namely, that the thought of “negating” the inadequacies of this film cannot be a thought that says: “Ah, it missed its chances, if only Del Toro didn’t have to answer to Hollywood”; “ah, it is just pop shit, it always would be, what did you expect, you should attack your own silly interest in it”; “ah, it’s pretty good actually, what should be negated is the apparatus surrounding it, its qualities could be free from it”. All of these are negations concerned with cutting what is of value free from the mold of banality that shapes and traps it, such that what comes loose — us as an audience, certain weird turns, the negative space of the empty cinema — can be taken as a grounding point while tossing the rotten bits to the curb.

But negation is not always made of razor wire. It is also a thick liquid, a pouring in and crystallization over what is to be negated in full, in all its complexity. In The Decline of the West, Oswald Spengler raises the figure of the pseudomorph (“false form”), a mineral compound that does not produce its own shape:

“But these are not free to do so in their own special forms. They must fill up the spaces that they find available. Thus there arise distorted forms, crystals whose inner structure contradicts their external shape, stones of one kind presenting the appearance of stones of another kind.”

Being Spengler, he meant this in a terrible way, and the figure appears as a way to attack the inadequacy of “the Arabian culture” as pseudomorphic (“All that wells up from the depths of the young soul is cast in the old moulds, young feelings stiffen in senile practices, and instead of expanding its own creative power, it can only hate the distant power with a hate that grows to be monstrous.”)

But it should be taken otherwise, just as that earlier figure I raised – that of ornament, of wallpaper, of surface modulations that do not build forms from scratch – should be as well. For if we want to complicate, misuse, and exploit a relationship to popular cinema, and particularly to films like Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, it should be a pseudomorphic relation, letting our thought swell into the forms that we may loathe.

Not taking these films as finished things to be judged as good or bad, as adequate or not, not as objects of critique to be scrutined, analyzed, sniffed or cheered at. Rather, merely as a texture of the given over which our watching, thought, care, and hatred necessarily pour and form, a set of inherited forms to be overwhelmed in the process of making an occasion for thinking. An occasion for negation to mimic, to take on shapes it otherwise would not, before outstripping them. In this way, the “distortions” and contradictions of the given form become raised to the level of ornament’s cartography, of pattern, of that which can be at last detected and traced. And then begins the harder work of another kind of negation, one that eats away at all that appears solid, including its own growth.

It’s in this way that the counterfactual, a consistently suspect form of historical thought, comes to be of real importance. Of course, we have no interest in saying, oh, wouldn’t it have been cool if it ended this other way? Too bad it didn’t! Maybe next time… Rather, to negate this film correctly is to let it be nothing but a set of details and stoppages, little restraints and clusters there to be noted precisely, taken up, and put to use elsewhere. Films will be recognized as inadequate not by their abjuration but by our extension of them, our outpacing, our saying this film is a belittlement of imagination precisely because it does not do any of what we are about to propose. As long as find ourselves capable of doing that, then we’ll go to the movies. We’ll leave them better for it, because we leave with more to say to one another than when we entered, having sloshed ourselves into and spilled out of those shapes. When this is not the case, then may the cinema perish.

In that spirit, five counterfactuals to end, not to say wouldn’t it have been cool but to say, let’s flood that basement.

One.

Sally does not end well in this version.

In version one (The Horror of Family as The Horror of the Couple), Kim – the step-mother to be – has no interest in becoming the surrogate mother of a problem child. And just as in the final version of the film (when she is about to be killed by the fairies, she calls out Sally! as though to remind them of their younger, tastier target), here too she is more than happy to sacrifice the Third to keep the Two running smooth and bedding down. She now stands at the front of the open fireplace grate in the basement, having just heaved the dark-haired youngster down the deep hole like a sandbag, falsely weeping as Alex rushes down the stairs. Oh baby, I tried to save her. I know you did Kim, I know. They get back to restoring the house. It looks great.

In version two (The Horror of the Family as The Horror of the Career), Alex is very committed to the success of his architectural project. He really wants to be on that cover. His daughter is a distraction. Why, after all, did he leave her with her mother in the first place? He knows about the fairies, has for a long time. The fairies, in fact, help with the restoration at night. They have very delicate tiny hands for doing filigree work, even if they are extremely pushy about wallpaper choices and prefer tones that are too muted to really make an impact on today’s critics, especially in the autumn light. But they have made it clear to him that if they are not fed his daughter’s teeth, they will undo all of his work and make completion impossible. They prove this one night by carving a surprising array of very unpleasant four letter words across an entire span of extremely expensive mahogany parquet just laid down. His workmen are more than a little confused about this littlest of graffito. It is a very difficult decision. He doesn’t know what to do. Sally wanders down to the basement again. He’s watching her there, talking to herself. No father should have to make this decision.

Cut to final sequence of film: the restoration is finished. And boy, does it look great.

Two.

Sally, having been the only one downstairs when the groundskeeper was viciously attacked and having been implicated previously in the razoring of Kim’s wardrobe, is understandably suspected of having tried to kill the old man. She is, after all, not quite right in the head. The film goes to lengths to indicate that this is unjust, that they cannot understand. We see her talking with the creatures. She turns the light off, and they creep onto the bed, nimble as spiders, chittering through their bat teeth.

However, she is still alive the next morning. In her hair, there are amazing delicate braids, twirled in a tiny, complex weave. She seems to be a model child now, and even helps out around the house, gives Kim nice hugs, “accidentally” calls her mommy one time while snuggling up drowsily to her.

The house is nearing completion. Sally has made a lot of little friends in the area, really come out of her shell. She is having a birthday party, surrounded by twelve grinning little girls, scrubbed clean and beaming. She asks her dad and the adults if she can give them a tour of the house. He’s proud of his work, sure, honey. She leads them to the basement, which has been spruced up, repainted. The dappled light falls through the arched window on Kim’s new wallpaper, which features rabbits winding through the briar. Cut to close up of the fireplace grate. It does not seem held on by any screws.

Let’s play hide and seek! Sally cries. I will go hide! All of you close your eyes and start counting!

They cheer. They do love their new friend, and they put their hands over their eyes.

Sally climbs the stairs. She bolts the heavy, nearly soundproof door from the outside.

Downstairs the girls are counting. Their little teeth, bright and small as bleached baby corn, catch that dappling light. They hear a slight clank as the grate door falls off. There is a rustling from the fireplace.

Sally, her mouth full of very straight white teeth, is grinning. After all, it feels good to keep up your end of the bargain. She is going to go get some more cake.

Three.

The fairies as almost anything other than those who just say We’re hungry, Come play with us, Give us teeth, Turn off the lights, et bloody cetera.

Replace audio track with any of the following options:

Creepier, although technically less threatening demands: Give us body hair… Shave it off, put it under the pillow! You’re not using it anyway!

Banal: Reset the router!

Pushy (as mentioned in Alex as monster of design version): No, no, don’t use the puce carpeting! We hate that faux cheer! Use the taupe! Restraint, give us restrained taste…

All of which to be followed by an even more elevated level of violence that is not causally linked to their incessant talking. (See immediately below.)

Four.

They actually pull some teeth.

Five.

Everyone has gotten it wrong from the start. Yes, they want teeth. Yes, they are invading the house, where Sally uses her Polaroid to scare them away with the light and, as a byproduct, capture their images.

Sally is dragged down the fireplace. Kim and Alex made it just a bit too late. Kim is shrieking. Alex tries to look stoic, fails. The house is now empty, abandoned, and as the film (much like the filmed version does, with Sally and Alex returning to leave a drawing of them as a happy family, which floats through the house down the fireplace, where we hear a pseudo-Kim conspiring with the fairies), a love letter from Daddy and Step-Mommy is carried through the empty house down the hole. This time, the camera follows it, winding slow through the dark. Gradually, there is enough texture on the walls to make it clear that the vertical tunnel is beginning to tilt toward horizontal and widening out. What we took as grime is, in fact, intensely detailed wallpaper, full of ornate arabesques and bold ogees, hypnotic, tattooed. We cannot tell if it is fully repeating or always different. But it is punctuated, every so often, by something hanging on the wall, as the camera turns to face more directly down its length. Hung at regular intervals, in responsibly Scandinavian natural ash frames, are the Polaroids taken upstairs: fairies leaping from the shelves, fairies dragging knives across the floor, fairies perched on Sally’s shoulder as they both scream into the camera. Fairies giving a thumbs up. Fairies with their arms around one another, tongues deep in one another’s mouths.

The camera swoops magisterial, glacially through the hallway and opens out into an cavernous room, focused low onto a oddly patterned floor. It seems almost to be made of ivory. Oh. It is a mosaic of teeth, buffed and polished, turned sideways and jammed together. The camera tilts up, onto an enormous set of patent leather shoes. It cants up at the enormous form before tracking backwards over the ground previously traversed, inch by inch. And there sits Sally, on a throne of teeth, graced with a crown of teeth.

Evan Calder Williams is the author of Combined and Uneven Apocalypse and Roman Letters.