Only fiction can be about the trivial without being trivial

Allison Benedikt does not love her dog. Benedikt recently confessed as much in Slate, explaining that having kids made her regret this earlier acquisition. Not because her dog’s bad with kids but because dogs are a lot of work, as are children, and children come first. (News at 11.) Benedikt admits to quasi-neglecting her dog, and strangely enough, dog neglect did not win over Slate's readers. Who would have guessed that a story about dog- and child-rearing attracts a few thousand comments.

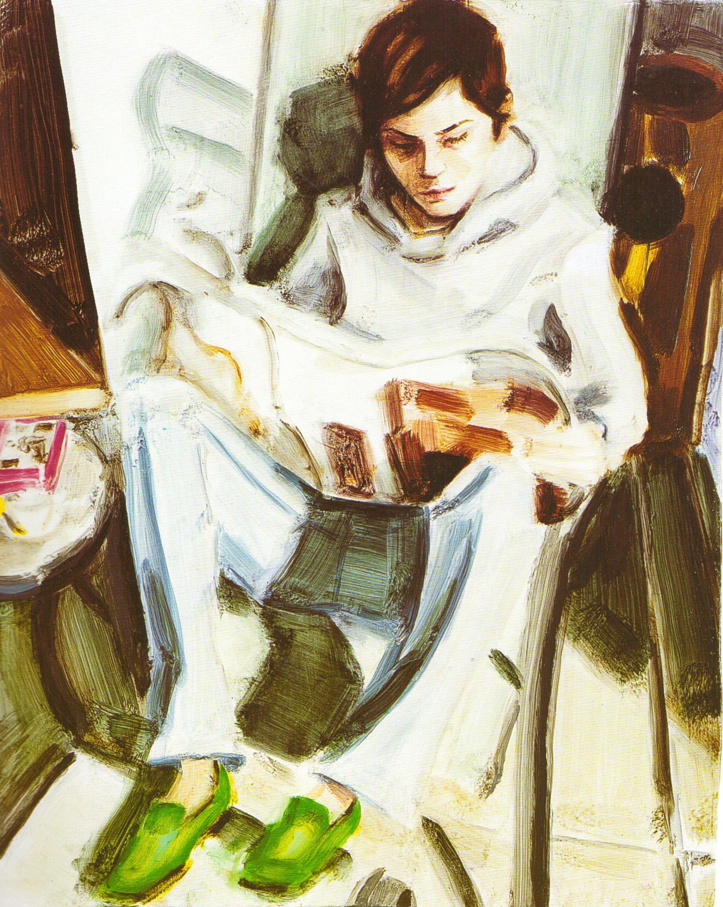

Had this story been a work of fiction, readers might have empathized with the protagonist, struggling to meet the needs of young children and a high-maintenance pet. That might have been a compelling (if depressing) story about the nature of love. But this is not fiction; it is instead perhaps the ultimate click-bait personal essay. A fictional version would probably not have attracted over four thousand comments. There is a real dog, whose photo accompanies the piece, as if to say, "Save me, reader!"

One may come away from the piece not only fearing for that poor dog but also for the concept of newsworthiness. If you go to a news website and read about how longhaired dogs require brushing, you may wonder why that’s taking up space that might otherwise be devoted to, say, updates from Egypt or analysis of the Zimmerman verdict. But the state of journalism is such that journalism professor Susan Shapiro, in a recent New York Times opinion piece, urges aspiring journalists to produce “three pages confessing [their] most humiliating secret.” Shapiro’s point — a fair one — is that this is what gets published.

Gawker’s Hamilton Nolan responded that “there is nothing more painful to watch than a writer desperately grasping at ever less important aspects of their own lives in order to make word counts, until they must simultaneously eat lunch and be writing about eating that lunch at the same time.” Nolan advises journalists to turn to the “billions of people in the world who do have interesting lives” and to tell their “stories of love, and war, and crime, and peril, and redemption.”

But there is nothing inherently wrong with writing about eating lunch far from any war zone. That could be a great story; it’s just not a news story. Online publications represent this type of writing as “journalism” and publish it in forums where readers expect journalistic standards of objectivity and relevance. Each story is framed as if it tells the story of some wide-reaching issue, even if it’s clearly anecdotes from the lives of the author and a couple of their friends. Readers end up discussing not the content of the story but whether it deserved to steal coverage away from more obviously journalistic subjects.

Yet readers are drawn to stories of domestic squabbles and social slights as they always have been, because these topics address something universal about the human experience. But the format that dominates many mainstream publications online, places like Slate, the online New York Times and New York magazine — a personal essay followed by a comments section filled with insults and complaints — undermines the effectiveness of the stories as stories, as thought-provoking glimpses of unvarnished humanity. Stories that require nuance and suspended judgment get neither when told online as personal narratives, as authors seek validation and many readers seek reasons to bash what they’ve just read or to play advice columnist for the author.

Writers who want to get published in prominent online places see what already appears in these publications — or how frequently which of their already published items are “liked” or shared — and rightly conclude that they must place their lives before a comments section and consent to an editorial process that tends to frame these stories in the most controversial way possible. (A woman’s essay about ambivalence surrounding her choice to start a family earlier than her friends gets the thud of a title: “Pregnant Too Soon.”)

Stories that once might have been channeled into fiction end up instead presented as news. Much click bait in these publications follows this pattern: A confessional writer — or one pushed into confession by market demands — will spill before an online audience. The confession will typically be intimate though not terribly outrageous. In a New York magazine essay, a woman cops to having 36 exes among her Facebook friends, only to qualify that by explaining that these are not all men she has ever dated or slept with. (Flirting apparently counts.)

But responding readers do not necessarily get beyond the first few words. “36 exes! Your poor husband :(,” writes one, to which another responds, in a similarly slut-shaming fashion, “if she's claiming 36. The number is definitely higher.” The discourse of the comment section invites readers to round the essay up to scandalous.

If the essay “succeeds,” commenters arrive in droves to tell the author how unimportant the topic is or to question the author’s intelligence or sanity. The author, hurt, may join the conversation, unedited and perhaps a bit unhinged, increasing the comments and the controversy. One writer, after contributing a post to a well-known parenting blog, defended herself in the comments, explaining that she “did not expect to be personally attacked on the subject of my parenting.” Another writer ended a health-blog essay about her own carelessness with birth control by asking, “Am I totally insane?” only to admonish her critics, in a later piece, “What so-called feminist or remotely compassionate human being goes into a discussion of this sort … and calls another woman … ‘insane’?” The pain of reading that complete strangers hate them — or for some authors, dealing with threats of violence — does not vanish for ambitious writers who know controversy sells. Readers don’t seem to bother to distinguish between the author and the essay’s constructed protagonist, and direct their bile at the author. As much as a writer might understand that his or her essay's voice is simply a construction, the hatred some readers direct at that construction sure feels personal.

We know that trolls can affect the reception of science reporting. A recent study reported in the New York Times showed that articles are read differently when accompanied by disparaging comments. Likewise, readers are likely to be dismissive about an essay about a woman’s coming-of-age when it is denounced as “first-world problems,” as many personal essays — particularly, it seems, those with female authors — are. When a confessional essay is said to showcase “first-world problems,” the criticism is essentially that the text is about small-scale concerns. Falling-outs with in-laws, crushes on co-workers: concerns by no means unique to the prosperous West.

The trolling attacks that personal essays can incite are virtually unimaginable for fiction. Readers are primed to declare whatever they have just read on the Internet as “wrong,” but fiction, meanwhile, can’t be wrong. A character can offend. The author may be a terrible person. The work itself may be dreadful. But “wrong”? What’s wrong in a personal essay is often what’s most right in a fictional story — moments where human behavior diverges, for unanticipated reasons, from the expected script. And only fiction can be about the trivial without being trivial.

The miracle of fiction is less about its execution than its promise: a story, not a delivery of life advice or an exhaustive documentation of reality. While personal essays fail as news because the subject matter isn’t newsworthy, they fail as storytelling because of how the texts are classified. A first-person protagonist and author may share a name and every event described may have happened as recorded, but if the document is labeled nonfiction, we respond to it differently. Imagine Lucky Jim presented not as a novel but as a personal essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education. We’d be chastising the writer for his poor work ethic and for not being appropriately appreciative of his good fortune to even have a job. Or compare Jami Attenberg’s recent novel, The Middlesteins, about an obese matriarch, with the New York Times’s health-blog series “Fat Dad.” Take a wild guess at which of the two inspired the following response: “Thank you for this very important piece about the importance of family meals.” No matter how rich the storytelling, the online personal-essay format, with its subtlety-free headlines and comments-welcome presentation, reduces these texts from nuanced portraits of human behavior to straightforward arguments about how to live.

The move of personal stories from fiction to nonfiction also affects another set: the friends and family of personal essayists. According to Shapiro, “The first piece you write that your family hates means you found your voice.” This ethically dubious approach to journalistic success is most troubling when the privacy violated is that of the author’s own children, who are not in a position to give consent (as I argued in this Atlantic essay.) But even when people not financially dependent on the author are exploited, the ethics are shaky. Behind-closed-doors behavior absolutely has a place in literature, but why must it be that of real, identified people? Readers seem quite capable of passionate responses to fictional people and their fictional dilemmas.

Labeling a text “fiction” is not a form of magic, capable of turning a complaint about a mediocre latte into great literature. Nor does that classification guarantee that fiction will be accepted as such, that Roth won’t be held accountable for Portnoy’s sins. We speak of “imagination,” yet recognize that much of fiction is fact that the author has chosen to classify otherwise.

But there are small-scale stories worth telling, and fiction is often their best literary home. In the privacy of our own living rooms – of our own brains – we all come across as entitled, celebrate minor successes and make embarrassing mistakes. Fiction allows us to tap into these often unsightly but fundamental aspects of our shared humanity. Reading fiction, we can relate without having to endorse.