There was a four-state alarm out on me. I don't know if the pigs knew it was me they were after, but at several railroad yards across the country they surprised me. Each time it was dark night and then the roar of the .45 smokeless and the blue-white flash of heavy revolvers lighting the night for a few brief seconds. Bullets bounded off the steel of rolling stock sometimes, splashing rust and bits of metal right in my face. But it's almost impossible to catch a man in a large freight yard without an army. I got through. And melted into the populace of the town of my birth, Chicago.

It was winter, cold and wet. I was dressed for the California summer except for a few articles I'd taken away from a hobo or two I'd met along the way. I had boots, gloves and a heavy wool shirt which I wore over a very light Pendleton jacket. A lady saw me and guessed by the state of my greasy apparel and red nose that I was in need of kindness. She took me to her apartment on the Near North Side and introduced me to the bath. The next day she bought me bullets and a huge warm navy surplus pea-coat, scarf, gloves, and heavy woolen trousers. I put the word out that I was looking for a relative who might be able to help me get out of the country, and gave the woman's address. The woman was white or Italian brown, whichever you wish. She was early forty and a little plump, but generally well-preserved because I guess she had the nerve of ten King Cobras. She was a dealer in narcotics. I dug her.

I spent most of my time hanging at the side of a front window overlooking the entrance. There were side windows to this particular apartment and telephone lines running not too far from the window. This was my planned escape route in the event of a surprise or betrayal. Picture a fool, gloved and pea-coated, hand holding from window to roof across a set of icicled telephone wires three stories up.

When she could get me to relax, we would sit on the couch. She would pretend that we were in Vera Cruz or Algeria, perhaps. They were still fighting in those countries then. There was a cracked plank in the hallway just outside her door. Every time someone walked past and stepped on the loose planking, my reflex would kick over her coffee table. I would flip out my .45 smokeless and grovel on her carpet trying to hide behind a coffee table the size of perhaps two postage stamps. But if someone had been breaking in the door, all they would have seen before I sent them to that big pig pen in the sky was the muzzle of that .45 army Colt and my mastery eye peeping around the table.

From Soledad Brother by George Jackson. This excerpt, along with a long passage giving advice about how to make bullets and learn how to shoot, appears in some editions but not in the original (nor many re-publications based thereon) for legal reasons.

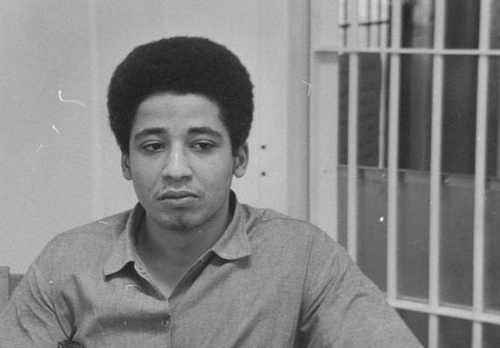

George Jackson was one of the greatest prison organizers in history, but is less-well remembered as a writer and theorist...unless you're a prisoner, prison abolitionist or prison administrator. Even having reading material or letters that mention George Jackson's name has been used as evidence towards getting people thrown in a SHU. It is also arguable that Foucault's concepts of biopolitics and the carceral state made famous in Discipline and Punish are appropriated from Jackson's (and his comrade Angela Davis') work on prisons. Jackson was murdered by prison guards in 1971.