Thinx ads are controversial because we aren’t used to regarding women in their underwear as fully human

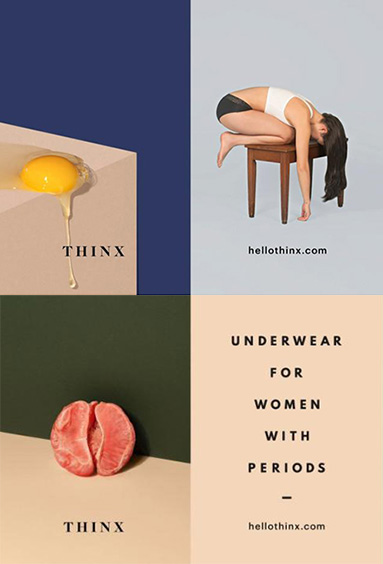

THINX, a menstrual underwear company, has recently been the subject of media controversy over the approval of their New York City subway and taxi ads. The contentious ads depict women clad in underwear, tank tops, and turtlenecks; some are posed casually, others in various postures of unease, apparently suffering from cramps. Several ads pair the model with an image of a single raw egg or a halved grapefruit.

The minimal compositions of the ads, their subdued tone, and the attire of the women are tame in comparison with similar, approved ads for women’s lingerie, breast augmentation, and protein powder, yet the contractors tasked with reviewing transit ads have raised concerns about the Thinx ads’ “offensive” nature and inappropriate content.

Thinx president Miki Agrawal has speculated about the reasons for the dispute: The ads don’t pander to the male gaze, they violate the taboo on menstruation, media contractors are sexist old boy’s clubs, and so on. But these explanations fail to fully address the root questions. What caused the Thinx ads to trouble review boards? The answer has to do with which representations of female bodies capitalist patriarchy deems fit for consumption.

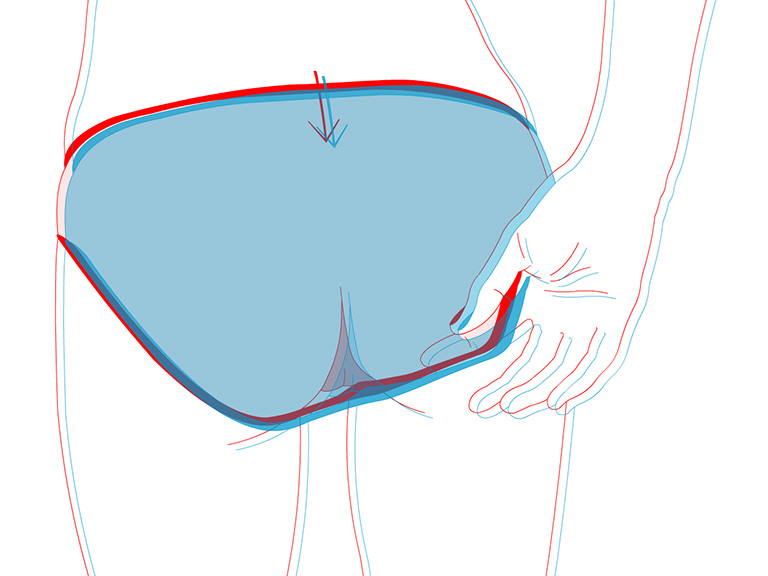

It comes as no surprise that when women are defined in terms of what they can offer men, “sexual object” emerges as their primary function. Research from the University of Nebraska shows that both women and men process images of women in bathing suits and underwear as objects rather than people. Sexualized women are read using what’s called analytic processing, which discounts spatial relationships between an object’s constitutive parts. Sexualized men, on the other hand, are perceived using configural processing, which is related to facial recognition and body-posture interpretation and looks for how parts of an object fit together as a whole. The study’s disturbing conclusion is that we simply aren’t used to viewing women in their underwear as complete human beings.

The Thinx ads disrupt this view of scantily clad women by emphasizing the visceral rather than the appetizing. The grapefruit half and egg yolks, removed from culinary contexts, seem mysterious, even ominous, as if possessing a life of their own. Similarly, the women in the ads are not catering to anyone; absorbed in their own sensations, they look away from the viewer or across their own bodies, aloof and inaccessible. This perceived indifference to the onlooker is enough to bother certain male viewers, who are accustomed to images that reaffirm their feelings of entitlement to women’s attention and bodies. As recent discussion of street harassment has made clear, women’s refusals to acknowledge men as imperious observers are commonly met with aggression, stalking, and overt violence.

By swapping sinuous poses and pouts for reflective gazes, the ads speak to women’s lived experience rather than to the viewer’s appetite. These are real women, with real bodies that bleed, cramp, and get nauseated. Declaring that Thinx is “for women with periods,” the campaign’s straightforward text reinforces women’s physicality while emphasizing their reproductive abilities. The ads present us with sexual women (attractive, young, reproductively viable) while refraining from explicit sexualization, subverting expectations and creating discomfort in certain viewers, whose desires have been evoked but left unsatisfied.

The Thinx ads also elaborate that they can be purchased not only by women but by “any menstruating human”—a progressive assertion, given that trans mainstreaming is still in the nascent stages. Thinx has released a boyshort-style design primarily marketed toward trans consumers and updated their copy to state that the product is “underwear for people with periods,” reinforcing their commitment to trans-inclusive marketing tactics. Acknowledging that not all those who bleed are women and that not all women bleed threatens patriarchal gender definitions and the power structures that enforce them. This societal edge bleed is refreshing amid more conventional advertising schemes, which push tried-and-true stereotypes to broaden audiences and maximize profits.

It is by now a commonplace that advertisers reinforce an ingrained tendency to view women as sexual objects to capture our attention and entice us to buy. We equate their consumable products with consumable female bodies, a conflation advertisers exploit with unapologetic zeal. Ads that directly compare women to meat (such as those for Carl’s Jr., Arby’s, Burger King, and PETA) are the most overt form of this exploitation. As Carol J. Adams argues in The Sexual Politics of Meat, meat is something that men (particularly white men) have controlled and consumed throughout history. By equating women with meat, advertisers draw on this history of white masculine entitlement and the idea of meat consumption as a superior, manly activity to tantalize male consumers. A truly masculine man may possess the tradable flesh of women and other races as easily as he does the tradable flesh of animals.

By contrast, the unidealized foods in the Thinx ads are purposely off-putting. The grapefruit, suggestive of female genitalia, looks dry, bumpy, and asymmetrical, while the raw egg yolk seems dirty, smeared directly on an unknown and possibly unclean surface rather than in a pan or a bowl. As symbolic representations of fertility and the female body, these imperfect and possibly contaminated foods imply that there are equally imperfect and uncontainable aspects of the female anatomy. Under the patriarchal gaze, an autonomous woman in her underwear is about as appetizing as an escaped egg yolk oozing its way off of a counter, and a beautiful woman suffering through her period regrettably embodies the sticky, odorous grossness of meat gone bad. The ads provoke this gaze and counter it with the idea of a woman unashamed of physical flaws and occasional bouts of uncleanliness. They challenge the societal fantasy of the poreless, powerless woman.

The association between women and contamination is ancient. All the major religions place restrictions on the day-to-day life of women following menstruation and childbirth, considering women at such times to be a spiritual and physical danger to others. Passages from Leviticus outline hygienic standards and purification rituals to mediate the uncleanliness of both women and food and explicitly forbid sex with a menstruating woman. Similarly, chaupadi, a Hindu tradition, forbids women from normal family activities during her period, sometimes requiring her to sleep outside the home. In Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva describes these rituals as an expression of fear at women’s procreative powers, arguing that such societies use boundaries between male and female as a foundation for the lawful organization of the world. Once masculine and feminine have been separated, it becomes easier to establish similar dichotomies such as clean/unclean, moral/immoral, and self/Other.

Bodily processes associated with women, such as childbirth and menstruation, evoke a particular horror in men, suggesting his bloody origins, his enslavement to the physical world, and the mysterious and terrifying power of female bodies. Freud, for instance, believed that disgust for menstruation expressed an “organic repression” ingrained in our biological makeup, while disgust for other bodily excreta, such as feces, was socially acquired. In The Anatomy of Disgust, William Ian Miller describes the process by which we use the physical aspects of a person and their perceived foulness to justify our already formed notions of their inferiority or immorality.

When disgust maintains social hierarchy its movement is not outward from some physical core disgust to more metaphorized moral and social domains. This disgust starts in the moral and social domains and moves toward concretizing itself in smells, cringes, and uglinesses. Once, however, the loathing of the lower orders ends in the perception of their odor there is a temptation to see a distinctly sexual, sometimes genderized twist to the style of subordination.

That is, we find facets of women’s bodies disgusting because womanhood is already inherently disgusting.

Body odor can affect anyone, but when women smell, particularly while menstruating, they invoke a profound sense of revulsion and contempt. Luckily, perfume, deodorant, and remedies for “feminine odors” can be readily purchased. With enough products at her disposal, a woman might one day become as clean and odorless as her ethereal, airbrushed image.

Conversely, refusing such an airbrushed image invites censure, as the Canadian poet Rupi Kaur discovered with her menstruation photo series. When Kaur uploaded an image of herself in bed with small bloodstains on her sweatpants and sheets, the photo was deleted from Instagram. The platform forbids posting sexually suggestive and nude photos, but there are no restrictions on stains, bodily fluids, and blood. Instagram restored the image and issued an apology only after the issue received considerable media attention, claiming that its erasure had been an accident. The misogynist implication that images of menstruating women are inherently obscene illuminates our societal preference for more easily digestible images of idealized women.

For women in a capitalist consumer society, double identification and the ability to perceive and associate with the desirous “male gaze” is a survival mechanism. Though female consumers are often described as senseless spendthrifts duped into believing an impossible ideal, the reality of women’s relationship to their images in the media is strategic. A woman can recognize a beauty ideal as insidious and unattainable, while also acknowledging it as an expectation, the approximation of which carries tangible social benefits. Ellen Willis declares that “for women, buying and wearing clothes and beauty aids is not so much consumption as work. One of a woman’s jobs in this society is to be an attractive sexual object, and clothes and makeup are tools of the trade.”

Most ads that claim to target women are in fact speaking indirectly to men. The woman is framed as a mediating presence at best, as secondary—she is the unaddressed reader who interprets the conversation between men and advertising, using it as a reference to anticipate what her straight male oppressors expect of her. The Thinx ad campaign does something different. It centers on another conversation entirely, one between women. Its self-contained women assure us, “We understand you. We know how you’ve suffered, and now you don’t have to”—a powerfully appealing statement.

Thinx knows that about half of women in their mid-20s identify as feminists, and these women earn more on average than men in their age bracket. Similar to Dove’s “Real Beauty” campaign, the Thinx ads position the company as an advocate for women’s health and self-esteem. Both companies hope to establish and commodify an intimate and understanding relationship with their female demographic. Disappointingly, both campaigns claim to use radically different models while still adhering to stereotypical conventions of female beauty: light skin, unblemished complexions, able bodies, long hair, and classically feminine features.

Insofar as images in public spaces may only be displayed with the backing of a corporate sponsor, I can only hope that the Thinx ad campaign elicits more of the like—clever, eye-catching, aesthetically sophisticated campaigns that, most importantly, acknowledge my autonomous existence. Unfortunately, my demographic does not control the major channels of image distribution and the campaign’s rejection from taxis proves that, as a society, we have not yet come to terms with the reality of liberated and imperfect female bodies. In the meantime, I, and women like myself, can take a small comfort in seeing our independently operating, feminine, bleeding bodies as worthy enough vehicles for a company’s expected profits—that is, as consumers rather than consumed.