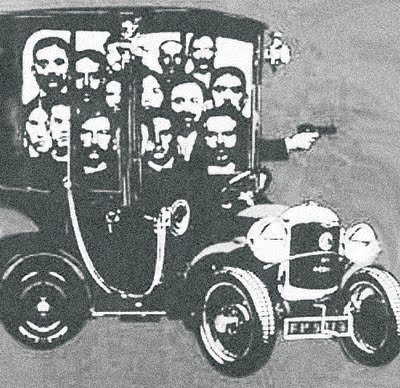

The anarchist belief in violent direct action, formulated in the policy of 'propaganda by the deed' (rather than by the word), reflected the particular bitterness of these struggles. Propaganda by deed was translated into action in three forms: insurrection, assassination, and bombing. The insurrectionary method, which had proved something of a fiasco in Spain and Italy in the 1870s, was not tried out in France. Instead, assassination became the principal weapon of revenge against the bourgeoisie and the figureheads of the State. The first wave of attempted assassinations was directed against political leaders throughout Europe: in the five years from 1878 there were attempts on the lives of the German Kaiser, the Kings of Spain and Italy, and the French Prime Minister. The death of the Russian Emperor, Alexander the II, by the 'People's Will' was, however, the only successful revolutionary execution of a reigning monarch.

There was a hiatus of ten years until the next batch of attempts on heads of State; in 1894 the French Prime Minister was stabbed to death, and the next decade saw the spectacular demise of a Spanish Prime Minister, an Italian King, an Austrian Empress and a President of the United States. In France, the gap between these two waves of political assassinations was marked by attempts on the lives of upholders of the ruling order in a more general sense. This time the victims were employers who had given workers the sack, a wealthy doctor, a priest, and brokers in the Paris Stock Exchange. The bourgeoisie began to be more than a little concerned when the anarchist 'propagandists by deed' began to use dynamite: in 1892 over one thousand explosions were reported in Europe. In Paris, bombs exploded in the Chamber of Deputies, a police station, an army barracks, a bourgeois cafe, a Judge's house, and the residence of the Public Prosecutor.

–Richard Parry, The Bonnot Gang

• • •

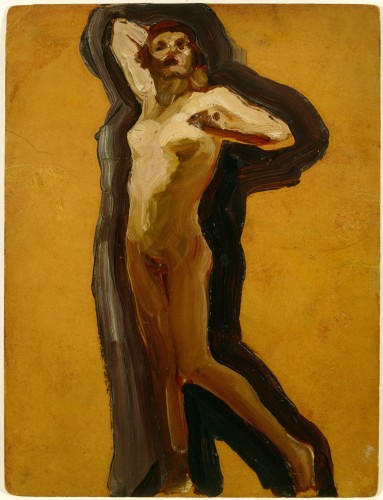

Here, then, surfaces the other side of the Baroness, as a figure of rage and revenge, as she takes us back to the earlier scenes of seething anger experienced in exploitative heterosexual affairs. Just as Biddle and Williams would be left with their legs shaking after kissing the Baroness (“Enveloping me slowly, as a snake would its prey, she glued her wet lips on mine,” as Biddle noted), so Logan was the quintessential emasculated man when facing the Baroness: “[he] whispered—blanched with fear—his knees knocking tato in his pants—oh—no—no—!” “The cowardly shitars,” she called Logan, while her poetry fantasized a quasi-rape in forcing down the walls of resistance of her reluctant male object: “Into castle of ice I will step BY CONTACT—seering fluid / forcing passage into walls of no reproach.”

Probably conceived and composed in prison was the infamous “Cast-Iron Lover,” her most controversial poem, whose antihero was Logan. This long poem of 279 lines is less a working through than a hallucinatory acting out of the breakdown of heterosexual relations against the backdrop of the war (although the war is never mentioned explicitly, the poem is brimming with violent imagery). When the poem was published two years later in The Little Review, it aroused controversy so divisive and violent that it post-traumatically evoked the recent battles at the war front. Her style itself was crystallizing as excitable speech, a speech act designed to arouse, provoke, incite, and agitate. In a raving tone, the sexes are violently hurled against each other in a fierce battle, with the conventions of love poetry loudly imploding in this grotesque love poem. “Heia! ja-hoho! hisses mine starry-eyed soul in her own language,” as she wrote...

–Irene Gammel, Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity

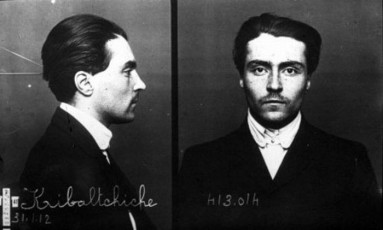

Although their founder, the handsome and charismatic Avraham Stern (who was murdered by British police in 1942), was an admirer of Mussolini who had shocked the Jewish community by proposing a military alliance with the Axis powers in 1941, Lohamei Herut Israel (or LEHI) - as Stern's group was officially known - was characterized less by uniformity of ideology than by a ferocious, almost suicidal dedication to driving the British from Palestine...

As the most extreme wing of the Zionist movement in Palestine - "fascists" to the Jewish agency and "terrorists" to the British - the Stern Gang was morally and tactically unfettered by considerations of diplomacy or world opinion. They also seemed to have been driven by apocalyptic despair and utopian hope. "There had never been a revolutionary-army organization quite like LEHI," writes one historian of Zionist violence. "A tiny group of strange men and women, despised by their opponents, abhorred by the orthodox, denied by their own, hunted and shot down in the streets; they lived briefly, during those dark years of despair, on nerve rather than hope."

–Mike Davis, Buda’s Wagon

• • •

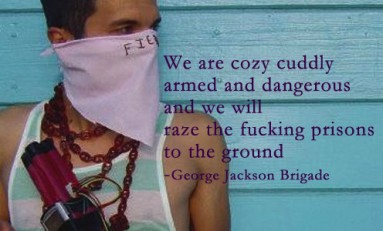

The FBI reported 1,178 bombings in the United States in the first seven months of 1975, resulting in thirty-one deaths and 206 injuries. In Seattle, there had been at least twenty-three bombings since 1971, and even this period had been "a comparative lull," as the Post-Intelligencer put it, in contrast to the sixty-six bombings that had occurred from January 1969 to June 1970. The advent of the George Jackson Brigade, as the alternative weekly tabloid Seattle Sun would remark in 1976, "shattered the illusion that urban guerrilla actions here are on the decrease."

-Daniel Burton-Rose, Guerrilla USA: The George Jackson Brigade and the Anticapitalist Underground of the 1970s

"Have you your Party card with you? Please let me see it."

From his pocketbook Rublev took the red folder in which was written: "Member since 1907." Over twenty years. What years!

"Right."

The red folder disappeared into a drawer, the key turned.

"You are charged with a crime. Your card will be returned to you, if necessary, after the investigation. That is all."

Rublev had been waiting for the blow too long. A sort of fury bristled his eyebrows, clenched his jaws, squared his shoulders. The secretary slid back a little in his revolving chair:

"I know nothing about it, those are my orders. That is all, citizen."

Rublev walked away, strangely light, borne by thoughts like flights of birds. So that's the trap–the beast in the trap is you, the trapped beast, you old revolutionist, it's you . . . and we're all in it, all in the trap . . . Didn't we all go absolutely wrong somewhere? Scoundrels, scoundrels! An empty hall, rawly lighted, the great marble stairway, the double revolving door, the street, the dry cold, the messenger's black car. Beside the messenger, who was smoking while he waited, someone else, a low voice saying thickly: "Comrade Rublev, be so good as to come with us for a short conversation..."–"I know, I know," said Rublev furiously, and he opened the door, flung himself into the icy Lincoln, folded his arms, and summoned all his will power to hold down an explosion of despairing fury...

The snow-white and night-blue of the narrow streets passed over the windows in parallel bands. "Slower," Rublev ordered, and the driver obeyed. Rublev let down the window–he wanted a good look at a bit of street, it did not matter what street. The sidewalk glittered with untrodden snow. A nobleman's residence of the past century, with its pillared portico, seemed to have been sleeping for the last hundred years behind its ornamental iron fence. The silvery trunks of birches shone faintly in the garden. That was all–forever, in a perfect silence, in the purity of a dream. City under the sea, farewell. The driver pushed down the accelerator.–It is we who are under the sea. It doesn't matter–we were strong men once.

–Victor Serge, The Case of Comrade Tulayev