Grigori Rasputin’s dick is on display at the Museum of Erotics in Saint Petersburg. Housed in a jar of formaldehyde, the member, which the museum’s owner claims he obtained from a French antiquarian, is quite sizable. Actually, it’s enormous for a human penis: Wide and meaty, it measures about a foot long. According to the museum, just gazing on the preserved member can cure a range of problems, everything from infertility to a humdrum sex life. But the specimen isn’t a human penis. It more than likely came from a horse.

It wouldn’t be the first time something inhuman was passed off as Rasputin’s dick. An earlier version circulated after Rasputin’s 1916 murder, legendary for being long and difficult: an initial failed poisoning, followed by multiple gunshots, a beating, and finally a drowning. Legend has it that in the midst of the horror show the man in charge of the grisly plot, Prince Felix Yusupov, somehow managed to castrate the mad mystic. Rasputin’s penis was supposedly scurried out of the country and ended up in the hands of Russian émigrés in Paris. There, his dick became a kind of religious relic of their vanished homeland, a potent piece of a vanished social order.

According to Rasputin biographer Patte Barham, the émigrés treated it as quasi-sacred, keeping it in a makeshift reliquary and venerating it. The powerful appendage of the dead mystic had strength or reassurance to offer the beleaguered community. By the 1970s, Barham reported that Rasputin’s dick looked like “a blackened, overripe banana, about a foot long, and resting on a velvet cloth.” When Rasputin’s daughter Maria discovered that others were in possession of the only remaining earthly piece of her father, she successfully demanded the member be returned to its rightful heir. It stayed with her until her death in 1977, after which it was confirmed that the relic was actually a sea cucumber.

Horse or sea cucumber, the fantasy of Rasputin’s mystically imbued potency was real enough. Relics are proven false over and over again, yet pilgrims still seek them out, yearning for the blessings the shriveled body parts of long-dead saints can bestow. Western Christianity has long fancied itself free from sex, looking down on “pagan” traditions where faith and sexuality intersect, but in fact penis worshiping has a rather robust tradition in Europe. Rasputin’s dick was by no means the first venerated member in Europe. It drew its power from already existing practices of venerating the body of Christ, whose foreskin was a much sought-after relic during the early modern era.

The Holy Prepuce, as it was known, was housed in churches across the continent, and figured in medieval liturgical texts. As the only remaining scrap of God on earth, it brought together the patriarchal powers of the church and the state in ritual obeisance. The foreskin aroused mystical visions and devotional practices throughout the history of the Catholic Church. But its near-total disappearance at the dawn of the modern era indicates that the two institutions felt compelled to hide their phallic object when faced with the end of their absolute reign.

According to the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas, Christ’s circumcision was performed in a cave on the eighth day, in accordance with Old Testament Law. Jesus’s brith milah served a two-fold purpose: first to maintain the genealogical covenant commanded by God of Abraham and his descendants; secondly to prove that, in fact, God had been rendered in human flesh. The anonymous author(s) of the Gospel of Thomas had little to say about the actual bris. They described instead an “old Hebrew woman” who took the discarded holy foreskin “and preserved it in an alabaster-box of oil spikenard.” The old woman then passed it to her son “a druggist, to whom she said, ‘Take heed thou sell not this alabaster box of spikenard-ointment, although thou shouldst be offered three hundred pence for it.’”

The druggist son apparently only heard the latter half of his mother’s strange and contradictory instructions, and sold the spikenard some decades later to Mary Magdalene. There is some satisfying irony in the most famous of biblical prostitutes buying the Holy Prepuce, in part because it would foreshadow the relic’s central place in the ecstasies of Christ’s brides in the church. But after the foreskin was purchased by the Magdalene, it disappeared for nearly eight centuries.

The first historic documentation of the foreskin was in the year 800, when it was given to Pope Leo III by Charlemagne. The Pope had just crowned Charlemagne emperor of the Carolingian Empire, a newly forged state carved out by Charlemagne’s successful military conquests through most of Europe. It was the least the Pope could do. Charlemagne had protected him when his Byzantine enemies ousted him from Rome and tried to cut out his tongue. The Pope was weak, but his gift allied him powerfully with the symbol of God’s earthly reign. How the Holy Prepuce ended up in Charlemagne’s hands is still a mystery (three equally ridiculous stories have been offered to explain the relic’s origins). But handled by Charlemagne, a king as much regarded for his considerable stature as his battlefield prowess, the foreskin was engorged with meaning.

Once brought to light, the Holy Prepuce reproduced itself at a rapid rate. In a few hundred years, dozens of churches, including Saint John Lateran in Rome (the seat of the Pope) claimed to own a piece or all of the Holy Prepuce. Some suggested that there were so many different Holy Prepuces because it could, like the fish and loaves, multiply to feed hungry pilgrims. In the official liturgy, the foreskin performed wonders on barren women, filling their wombs, and eliminating pain from subsequent delivery. Queen Catherine of England borrowed the relic at the Abbey Church of Coulombs in the early 15th century. Like Rasputin’s penis, the redeemer’s foreskin apparently was miraculous: An heir to the throne appeared nine months later, and the Queen built a sanctuary to house the relic once she was done with it. The Holy Prepuce worked miracles in service of the state, reproducing the physical bodies of kings.

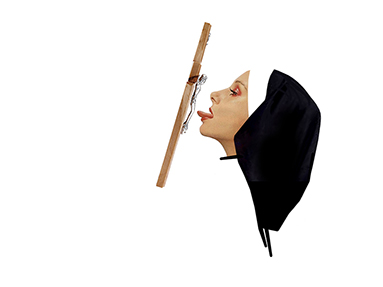

In the visions of nuns, however, the official narrative of the Holy Prepuce held little sway. After all, a good nun would have little need for either sex or its procreative results. As a bride of Christ, her union with spouse would be spiritual and transcend any physical needs or desires. But it wasn’t, of course, that simple. For nuns—particularly mystics—the holy member represented instead a different kind of power. In the hands of and under the gaze of these women, the Holy Prepuce morphed into an object of desire where repressed sexual cravings could find an outlet. The languages of veneration and sexuality intersected, attaching themselves to the fantastical totem of Christ’s foreskin.

By the 15th century, the Holy Prepuce had become the desirous object of many mystics’ visions. Bridget of Sweden recorded the revelations she received from the Virgin Mary, who told the saint that she saved the foreskin of her son and carried it with her until her death. Catherine of Siena, the patron saint of Italy, imagined that her wedding ring—exchanged with the Savior in a mystical marriage—had been transmuted into the foreskin. In her Revelationes (c. 1310), Saint Agnes Blannbekin recounts the hours she spent contemplating the loss of blood the infant Christ must have suffered during the circumcision, and during one of her contemplative moments, while idly wondering what had become of the foreskin, she felt the prepuce pressed upon her tongue. Blannbekin recounted the sweet, intoxicating taste, and she attempted to swallow it. The saint found herself unable to digest the Holy Prepuce; every time she swallowed, it immediately reappeared on her tongue. Again and again she repeated the ritual until after a hundred gulps she managed to down the baby Jesus’ cover.

The piece of Christ’s flesh became a stand-in for his whole body, a body which could be lusted after by chaste women. In the visions of these women, Christ’s penis was no rigid signifier of monarchical power. Transferred to the hands of his brides, the foreskin came alive. It enveloped bodies and danced sweetly on tongues, demanding to be swallowed and consumed. The eroticism of religious ecstasy, fantasy, and desire played out over the body of Christ.

In these nuns’ religious transports, metaphysical union played out in the language of desire and strained metaphors for orgasm. Eating and hunger were figures of a never-satiated desire to be filled. In their reveries, women rarely eat ordinary food, as the flesh of Christ alone can fulfill them. Instead they drink and feast on the blood and body of the Eucharist, the food of Christ’s suffering and his physicality. But they can’t be satiated: Blannbekin swallows over and over again. Catherine of Siena, too, whose Dialogues (1377) were dictated in an ecstatic state, spoke of visions in which consumption and consummation became interwoven terms:

“My beloved," [Christ said], "you have now gone through many struggles for my sake. . . . Previously you had renounced all that the body takes pleasure in. . . . But yesterday the intensity of your ardent love for me overcame even the instinctive reflexes of your body itself: you forced yourself to swallow without a qualm a drink from which nature recoiled in disgust [i.e., pus from the putrefying breast of a dying woman]. . . . As you then went far beyond what mere human nature could ever have achieved, so I today shall give you a drink that transcends in perfection any that human nature can provide. . . ." With that, he tenderly placed his right hand on her neck, and drew her toward the wound in his side. "Drink, daughter, from my side," he said, "and by that draught your soul shall become enraptured with such delight that your very body, which for my sake you have denied, shall be inundated with its overflowing goodness." Drawn close . . . to the outlet of the Fountain of Life, she fastened her lips upon that sacred wound, and still more eagerly the mouth of her soul, and there she slaked her thirst.

In the midst of Catherine of Siena’s rapturous state, the saint gave the body of Christ a feminine form, homologizing the wound to a woman’s breast and vulva. Drinking and sucking is “enraptured delight.” Catherine’s chastity and self-abnegation is rewarded in homoerotic fulfillment. In other passages, the saint likens the “affection of love” in Christ with the “pleasure [of] sensual self-love” as though searching for relief of painfully frustrated physical desire with spiritual fulfillment.

With this unruly erotic attachment to His body, it’s no surprise that by the nineteenth century, the Church wanted to end this kind of sexualized mysticism. Such veneration had already become an object of ridicule among Protestants—reformers like John Calvin joked and Voltaire took witty aim at the foreskin and its worshippers. In response, the Church began calling the foreskin relics “curious,” and demanded that the Holy Prepuce be put away. After enjoying the light of desire, it was hidden in the dank vaults of cathedrals and churches, removed from the gaze and fantasies of those who would seek to worship the object. To keep the body of Christ pure and restrict its temptations of women, their outlet for sexual fantasy needed to be purged. Hastily recast, the mystics were no longer visionaries, but hysterics.

At the end of the 19th century, when women’s sexual desires were more openly discussed, and anti-Semitism loomed large in the Catholic Church, the prepuce threatened the official line with a material reminder of the disruptive power of female sexuality and of the redeemer’s Judaism. So the Vatican issued a decree declaring the object forbidden. Anyone who wrote or spoke of the foreskin was threatened with excommunication, and the Holy Prepuce virtually disappeared. Once purged, the erotic gaze of women could be blocked and blinded.

One of the last written references to the foreskin relic is found in Ulysses. James Joyce had no use for the threats of holy men and poked fun at the foreskin in his novel:

…the problem of the sacerdotal integrity of Jesus circumcised (1 January, holiday of obligation to hear mass and abstain from unnecessary servile work) and the problem as to whether the divine prepuce, the carnal bridal ring of the holy Roman catholic apostolic church, conserved in Calcata, were deserving of simple hyperduly or of the fourth degree of latria accorded to the abscission of such divine excrescences as hair and toenails.

Joyce’s blasphemous joke was taken directly from the anti-papist tracts he had been reading, namely a short book about the foreskin written by the converted Dominican priest Alphons Victor Müller. Joyce’s had underlined in red crayon all of the portions of Müller’s that dealt with the foreskin and openly mocked the sexual license of Catholic religious institutions. Müller particularly singled out the ecstatic worship of mystics as “unfortunate hysterical-sexual aberrations.”

In addition to exhuming the sexual history of the prepuce, Joyce’s joke pointed to another problem: a small church twenty miles outside of Rome, in the town Calcata where the last remaining Holy Prepuce was held. In defiance of the Pope, the town proudly kept their relic in an elaborate, jeweled box and annually paraded it through Calcata’s crumbling streets. But in 1983, the venerated relic disappeared. By then, Calcata had become a hotspot for young Roman gentrifiers who found the annual foreskin festival amusing. They too began writing about it, inviting their friends to come and see the local show. The Pope demanded, once and for all, that the prepuce must be put away. And so it was conveniently stolen, most likely by the local priest. When questioned by the media, the priest demurred, citing the decree of excommunication.

The Church, it seems, finally decided that the Holy Prepuce was not as valuable nor as important as other shriveled body parts. An arm, a femur, a tuft of hair preserved from corpse of a mere saint were fine to venerate, to even talk about; they never inspired erotic visions or rapturous physicality. But Christ’s dick was dangerous—too obviously fleshy, too desired, too erotically malleable. Once the gift of kings, later the object of women’s erotic desire, the relic could not survive the puritan melding of sexuality with sin. That tiny piece of shriveled foreskin, was persistent reminder of Christ’s flesh incarnate which, to its Protestant detractors, was proof of Catholicism’s pagan licentiousness.

So the Catholic Church reformed; it put away the foreskin, denied its existence, and rewrote the history of the erotic pleasures of mystics. Severed from any remainder of his flesh on earth, Christ’s body was safe during the metaphorical consumption of communion. Christianity was now on the same page: The idea of Jesus’ sexuality was heresy; the erotic earthly pleasures of his body were purged. Phallic desires were for heathens, the object only of scorn and ridicule.