The supposedly natural emotions of love and compassion are used to compel many people, especially women, to work for free.

At an interview for a mental health nursing program, I was asked what I would do if a patient wet themselves at the end of my shift. In terms of my experiences of nursing, the question made no sense: In reality, the last half hour of a shift is spent handing over patients to new staff coming on duty. It would be their responsibility to clean my patient. But at interview, I said what I knew I was supposed to say: that I would clean the patient myself, regardless of when my shift ended. Wannabe nurses must demonstrate their compassion. And compassion, we are taught, means cleaning shit for free.

I work in the U.K., but my experiences as a trainee nurse will be familiar to other nurses in the U.S. and worldwide. In many caring institutions, stretched resources mean high ratios of patients to staff. Nurses must meet the complex and diverse needs of the people they care for—washing, dressing, meal times, medication, counselling, liaising with social services—at the expense of lunch breaks and evenings. Feelings of guilt and panic pervade the working day. If you leave exactly when your shift ends, you feel you are failing your patients. If you stay late, you are effectively working for free and affirming the expectation that you should work for free, making it harder for your colleagues to leave on time. You are trapped between two kinds of compassion: your compassion for your patients, and your compassion for your co-workers.

Reports of neglect and abuse in hospitals and care homes appear with alarming regularity. Received narratives blame “burn-out”: understaffing, low wages and squeezed margins transform overworked and overstressed carers into monsters. The proposed solution is extra vigilance and “Compassion Training.” Shifting the question of working practices and worker wellbeing onto the terrain of compassion is a sleight of hand. It implies that care workers should police themselves and their colleagues rather than fight collectively for better pay and conditions. By this account, compassion flows in one direction only, from nurse to patient, and never between nurses, or from the nurse to her or his own family and friends.

Nurse-lecturers, who have swapped bedpans for classrooms and higher salaries, use some startling methods to help student nurses adopt a compassionate approach. We are encouraged, for example, to imagine that a patient is our mother, to help sweeten the bitter pill of unpaid overtime. This assumes that the mother-child relationship invariably provides a robust and appropriate model for compassion. In reality, many people have messy or even abusive relationships with their mothers. Our work as nurses brings us into contact with the complexity of actually existing family relationships. We treat patients who no one visits, or who are aggressive and challenging. The training we are given in compassion asks us to ignore compassion’s basis—attention to lived experience—in favor of a platitude about the mother-child bond, half fairytale and half emotional blackmail.

Like everyone, nurses all have different personal experiences of being mothered or being mothers. In drawing on naturalized ideals of tenderness and care, the teaching of compassion makes heavy presumptions about nurses’ own families, or disregards them entirely. In the essay “Caring: A Labor of Stolen Time: Pages from a CNA’s Notebook,” first published in Lies journal, the writer points out that many care workers are forced to neglect their own families, sometimes overseas, whilst engaging in long hours of low waged caring labor: “As if eight hours and the emotional shrapnel that spill over into our non-work time is insufficient mental colonization. Now, they even try to get family involved… We are torn from our family, and yet our shameless bosses try to milk our love for family.”

Of course, the majority of care workers—parents but mostly mothers, children but mostly daughters, spouses but mostly wives—never receive any wages at all. Within families, and other close interpersonal relationships, love and guilt are the mechanisms by which caring labor (cleaning, wiping, feeding and so on) is extorted from a largely female workforce. Perhaps this is what nurse-lecturers are really alluding to when they ask students to imagine their patients as their mothers. When women, who dominate caring professions, take their capacity to care away from the private sphere and sell it on the labor market instead, the same mechanisms—love and guilt—are called upon to bridge the shortfall in staff, resources and wages that characterize many caring institutions, whether they are run for profit or by the state.

The pact of caring labor is double-edged. Caring means giving more than you get, or giving without hope of receiving. But in order to receive this supposedly immeasurable care, you must first make yourself sufficiently loveable. There is a reason mothers implore their children to settle down and start a family. You must make friends or have children or find a life partner. You must ensure those people stick around long enough to care for you when you get sick or grow old. You should try to avoid falling ill in prison. Inevitably, not everyone is willing or able to meet these demands. Those who are challenging or aggressive can struggle to find people to meet their care needs. They might be left in pain, or go hungry, because they cannot make themselves sufficiently likable. Because they cannot form the kinds of relationships within which caring labor is dispensed (e.g. marriages, friendships, families). Whilst nurses are paid to form these relationships with everyone and anyone, in the context of over-stretched health care systems, it is inevitable that the most challenging, least likeable patients will lose out. This is one of the unintended implications of advising nurses to pretend that patients are people they love. It is hard to love people who are abusive or ungrateful or racist. Compassion is in permanent crisis: love and guilt cannot ensure that everyone in society is adequately cared for.

Feminists differ in their attitudes towards caring labor. Valerie Solanas, in the SCUM Manifesto argues that care work is a demeaning artifact of a society controlled by men:

The reduction to animals of the women of the most backward segment of the society—the “privileged, educated” middle-class, the backwash of humanity—where Daddy reigns supreme, has been so thorough that they try to groove on labor pains and lie around in the most advanced nation in the world in the middle of the twentieth century with babies chomping away on their tits.

In the SCUM Manifesto, Valerie Solanas proposes that “thrill-seeking females overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.” In her vision of post-revolution society, all work will be performed by machines. Caring labor will be eliminated and will no longer be constitutive of expressions of love between individuals. Instead, women will spend their newfound leisure time expressing love for each other through intellectual discourse and great projects (e.g. curing death).

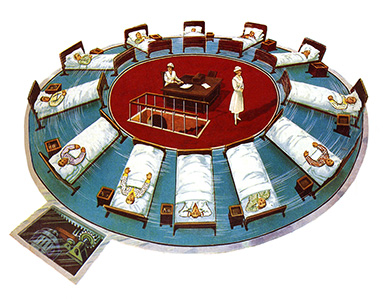

While increased leisure time and revolutionized interpersonal relationships have not yet been forthcoming, technology has already been employed in a range of caring tasks from baby formula milk or TV as babysitter to animal robots. However, we remain a long way from machines raising the next generation of workers and carers. As demonstrated by Harry Harlow’s heartbreaking experiments raising baby monkeys in isolation chambers with inanimate robot mothers, the task of reproducing socialized primates is complex and nuanced. So far, despite the deficiencies of some human carers, we do not have a machine that can care for the sick or bring up a child.

Many feminist theorists disagree with Solanas’s analysis. They argue that while in patriarchal capitalist societies women are overburdened with the tasks of love and care, these tasks are an inherent part of what it means to be human. For example, Selma James, co-founder of the International Wages for Housework Campaign, defends care work like this: “Mothers feeding infants, in fact all caring work outside any money exchange, is basic to human survival—not exactly a marginal achievement. What, we must ask in our own defense and in society’s, is more important than this?”

Thus the International Wages for Housework Campaign demands a substantially reduced working week, a guaranteed income for all (women and men) and free community-controlled childcare. In her essay, “Wages Against Housework” Silvia Federici argues that these demands are revolutionary—they have the power to undermine capitalism and to radically transform society: “Wages for housework, then is a revolutionary demand… because it forces capital to restructure society in terms more favorable to us and consequently more favorable to the unity of the class.”

In advocating for the defense of, and investment in, caring labor as a central revolutionary demand, the International Wages for Housework Campaign presents caring work as an essential and redeeming feature of humanity. Unlike Solanas’s vision of mechanized care, in this version of feminism, caring labor is not eliminated—it remains an important aspect of human relationships and expressions of love within those relationships. Care for the sick would still depend on love, whether within close interpersonal relationships or as part of a more generalized, universal love for all people.

Of course, in this post-revolutionary, transformed society, caring labor would no longer be primarily the domain of women. Freed from wage slavery, men and women would both have time to care for the young, old and sick. The collapse of the patriarchal family, a cornerstone of capitalist society, would engender the development of communized care institutions: People would continue to express their love for each other through caring work but this love would no longer be confined within exploitative interpersonal relationships or waged employment (i.e. families or existing social service and health care structures).

Silvia Federici, and others in the Wages for Housework movement, are skeptical about the role of technology in revolutionizing care work. They do not share Solanas’ optimism about machines. They point out that the production and consumption of technology is characterized by the exploitation and domination of workers, for example in factories like Apple-Foxconn. Machines are created by capitalism and therefore should not be trusted. But capitalism also requires workers who are able to work. If workers get sick, someone must take care of them, whether within families or healthcare institutions. As we have seen, love and guilt are the key emotional mechanisms by which capitalism appropriates (mostly female) unwaged caring labor to these ends. Perhaps then, we should also be skeptical of models of utopia that revolutionize the organization of society but leave care work, and its associated emotions, intact.

Is it possible to imagine a restructured society in which love remains the primary motivation for engaging in care work but where this labor is provided freely, without exploitation? We might assume that rich women love their families, but just as they don’t work in the factories where their iPhones are made, they rarely perform the hard graft of caring labor themselves. Instead they employ nurses and nannies. The reason that some working class women perform care work for rich people as well as for their own families and communities is not that they experience love more intensely. Or if they do, perhaps they experience it more intensely because they are required by capitalism to perform this labor. Ultimately they do it because they do not have a choice.

There are potentially a million different possible ways to treat the sick, raise children or organize intimacy. It’s at least imaginable that in a different social form we could cure ourselves with shared knowledge of pharmacologically active substances, or that sick people might choose to meditate on their pain alone, or countless other examples. In a fully communized society, it might be possible to retain both love and iPhones, but the conditions of their production and consumption would need to be radically transformed. It might be necessary, as Solanas suggests, to de-couple love from care work. Whatever happens, we must stop taking it for granted that women care and want to care. And we must begin to investigate the meaning of that caring.